RIP FPTP: Why first-past-the-post will be the real loser today

Article

As voters head to the polls for the closest fought election in generations, no one can be sure who will emerge victorious. The final ICM poll for the Guardian has the Conservatives and Labour tied on 35 per cent.

One thing that is certain, however, is that Britain's first-past-the-post voting system is going to be the big loser. Unless the polls have got it badly wrong, we are headed for another hung parliament. In which case, it turns out that the inconclusive result of 2010 was not a one-off aberration, as advocates of first-past-the-post liked to argue at the time, but a consequence of long-term changes in voting patterns across the UK – declining support for the two main parties and divergent support for them across the nations and regions of the UK – that significantly increase the likelihood of hung parliaments in the future. And if first-past-the-post can't deliver 'single-party majority government' then it fails on its own terms, since this is the central claim of those that champion it.

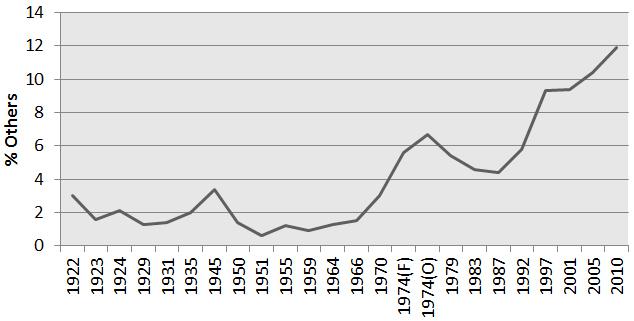

First-past-the-post (FPTP) is only able to deliver single party majority government if there are two parties competing for power, as was the case during the hey-day of the British two-party system. From 1945 to 1974, the combined share of the vote for the Conservatives and Labour hovered around 90 per cent. But the two-party system has been in decline for years – and the British political landscape irrevocably transformed. The 2015 election is being fought out across multiple multiparty systems – there are five parties in England and Northern Ireland, six in Scotland and Wales – which fundamentally undermines the FPTP logic.

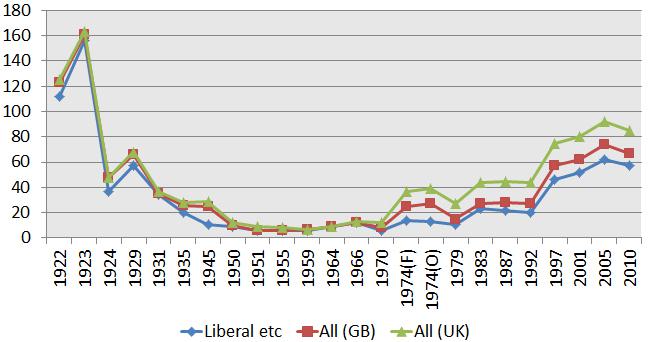

Not only are voters willing to support 'third parties', these parties have proved capable of winning seats in the House of Commons, in part because their support tends to be geographically concentrated in the nations and regions of the UK. The Lib-Dems' stronghold in the south west, the rise of nationalist parties in the Wales and Scotland, and Northern Ireland's distinct party system mean that these parties have been able to win around 85 seats in recent elections.

Figure 1: The rise of third parties, 1922–2010

Figure 2: Third-party seats, 1922–2010

Looking at the various seat projects for 2015, it looks likely that even with the collapse in support for the Liberal Democrats, third parties will win even more seats this time around than they did in 2010. This is, of course, largely down to the dramatic surge in support for the SNP, which could end up with as many as 50 seats. Peter Kellner's eve-of-poll forecast has the third parties picking up a whopping 103 seats: 48 for the SNP, 31 for the Lib-Dems, two Ukip, three Plaid Cymru, and one Greens, plus the 18 MPs from Northern Ireland.

If third parties are winning anything between 80–100 seats, that makes it increasingly difficult for either Labour or the Conservatives to win an outright majority. A cursory glance at British history shows this to be the case: under FPTP, multiparty politics often produces indecisive results, as the elections of 1910 and February 1974 prove.

It is well known that FPTP fails the 'fairness' test: it is not proportional, and so major discrepancies exist between the number of votes a party secures and the proportion of seats it wins in the Commons. It will be Ukip that suffers the most from this tonight: they look set to get three times as many votes as the SNP, but will win at best a handful of seats. The SNP, by contrast, on 4 per cent of the vote, is likely to become the third-largest party in the Commons, and possibly will hold the balance of power. Indeed, the greater the number of parties competing under FPTP, the more disproportional the result becomes, and the more unrepresentative future parliaments will become.

Multiparty politics also aggravates a wider set of deficiencies associated with FPTP. For instance, the rise in support for third parties greatly reduces the chance of individual MPs securing a majority of support (50 per cent or more) among their local electorate, which raises serious questions about the legitimacy of their claim to represent their constituents. It also exaggerates the territorial imbalances across the nations and regions of the UK, and makes the country appear more divided than it actually is. It undermines Tory representation in the north of England, for example, and that of Labour in the south of England. And, most dramatically, it raises the prospect of handing a landslide of seats to the SNP on a minority of the vote. The centrifugal nature of FPTP undermines the integrity of the UK itself.

In a time of greater political pluralism, British politics is no longer well-served by a voting system that was designed for a two-party era, nor are the interests of British democracy. Arguably the biggest democratic deficit associated with FPTP is that election outcomes are effectively decided by a handful of voters who happen to live in all-important marginal seats. The overwhelming majority of us live in safe seats where we are increasingly neglected by the political parties both during and between elections – and where we have little chance of influencing the result of general elections. IPPR calculates that just over 460,000 votes – or a miniscule 1.6 per cent of the electorate – determined the outcome of the 2010 election. There is no reason to believe that the 2015 election will be any different.

Intended for a world that no longer exists, first-past-the-post looks increasingly anachronistic in the fluid and fragmented world of contemporary, multiparty British politics. Unless FPTP is reformed – which is to say, replaced – the UK will be left with the 'worst of both worlds': a voting system that neither delivers fair representation nor single-party majority government.

{{ readMore("id=667", "contentType=publications") }}

Guy Lodge is associate director for politics and power at IPPR, and an editor of Juncture.

Related items

Who gets a good deal? Revealing public attitudes to transport in Great Britain

Transport isn’t working. That’s the message from the British public. This is especially true if you’re on a low income, disabled or living in the countryside. The cost of living crisis has exposed the shortcomings of our transport system,…

Bhargav Srinivasa Desikan on TalkTV discussing AI

IPPR's Bhargav Srinivasa Desikan on TalkTV discussing his new report on the impact of generative AI on the UK labour market.

Transformed by AI: How generative artificial intelligence could affect work in the UK – and how to manage it

Technological change is a good thing. It has brought exponential gains to living standards and is the foundation of modern society. Yet unmanaged technological change has always come with risks and disruptions.