A return north: reflections on IPPR Scotland’s tenth anniversary conference

Article

There’s nothing like moving away from Scotland to remind you just how Scottish you are.

A year into living in London — dodging the Central line, being told I have a “lovely accent,” and trying not to roll my eyes too aggressively — I realise how much Scotland has shaped the way I think about justice, community, and who gets heard.

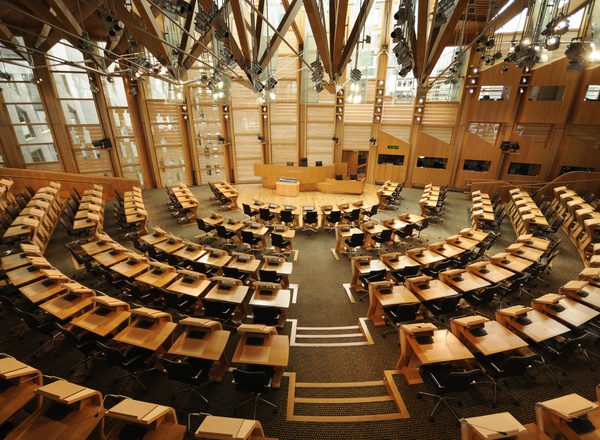

Heading to Edinburgh for IPPR Scotland’s tenth anniversary conference felt a bit like returning to see an old friend: familiar, comforting, but also revealing in ways I didn’t expect. The day was packed with speeches, panels, and the usual “politics but make it polite” Scottish energy. Beneath it all, three themes kept resurfacing: devolution, lived experience and sector insight, and the slowly spreading mould patch that is our national trust deficit.

Devolution is working but it needs more muscle

First minister John Swinney’s keynote kicked things off with 30 years of devolution memories - part history lesson, part reminder of everything Scotland has achieved despite Westminster’s tight grip on the remote. He called devolution “fragile but essential”, which sums up Scottish politics better than most constitutional textbooks.

We all know the score: Scotland wants to solve Scotland’s problems, but the tools aren’t always in the toolbox. Listening to Swinney, I was reminded that Scotland does best when it uses the full powers of devolution to drive distinct and progressive policy change. The social security reforms, the housing protections, even the attempts to tackle child poverty show what can happen when decisions are made closer to the people affected.

What struck me most wasn’t the constitutional talk but the underlying tone: Scotland can and should be a better country. The next decade can’t just be about defending what powers exist; it has to be about a continual reassessment of devolution and, where appropriate, strengthening devolved powers. Scotland must be doing more than tinkering with UK policies.

Presence isn’t the same as influence

If the ministerial speeches were the starter, the panel on poverty served the real, unfiltered main course: brutal truths about impossible choices, crushing bureaucracy, and systems that wear people out rather than help. Panellists with lived experiences of poverty laid it bare - Universal Credit must actually cover essentials, or inflation drags families back into hardship. One panellist waved a packet of custard creams he had brought with him. Ten years ago, he paid 20p for it; today it costs him £1. Another speaker called out the common myth that Scotland and the UK are poverty-free zones, rightly pointing out how such views ignore harsh realities.

And here’s the throughline that lodged in my head: “We have access but not impact.” That’s it. That’s the whole tension. The panellists urged decision makers to treat people with lived experience of poverty as experts. Scotland prides itself on inviting people into consultations, working groups, advisory boards. But being asked for your experience and then watching nothing change is not empowerment. It’s admin.

Speakers on the net zero and economy panels said versions of the same thing. Net zero isn't a solo act - it demands delivery and a full cast of collaborating sectors, or the curtain never rises on real impact. Only tangible delivery generates the emissions cuts, community benefits, and economic returns the climate transition requires. Scotland has the talent, the ideas, the renewable energy, the know-how. But clarity, follow-through, a plan that doesn’t shift with every political breeze? That’s where the frustration lies.

It reminded me of the very issues I write about, especially around race. People are endlessly consulted, endlessly surveyed, endlessly asked for perspective, but change remains stubbornly slow. Scotland loves the idea of inclusion. But real inclusion? That’s when institutions stop collecting stories and start acting on them.

A national trust deficit: elephant in the room

By the time Anas Sarwar, the leader of Scottish Labour, took the stage, trust was already the ghost haunting the room. He said Scotland needs “big, bold, radical change,” but what really landed was my diagnosis behind that call: people simply don’t trust that politics can deliver anymore.

You can feel the exhaustion everywhere - in people’s voices when they talk about the NHS, in the sharp questions from the audience about homelessness, in the scepticism toward anything branded a “transition” or a “revamp” or a “long-term vision.”

For some communities - those facing racism, those navigating the hostile environment, those pushed to the margins - the trust deficit is old news. Scotland talks a better game than Westminster when it comes to inclusion, but talk doesn’t soften borders or fix housing or dismantle systemic bias.

Trust isn’t a vibe. It’s a result. And right now, too many people feel they’re contributing their stories, their expertise, their hope, and getting very little back.

-

Walking out of the conference, I didn’t feel inspired in the “uplifting soundtrack and heroic montage” sense. I also didn’t feel hopeless. What I felt was something more honest: recognition.

Scotland is trying. Scotland is stubbornly, almost endearingly determined to be better than its circumstances. And the people in that room (campaigners, researchers, front-line workers), are the ones pushing it forward, inch by inch.

Yes, devolution is too limited. Yes, lived experience is being used more than it is being acted on. Yes, trust is hanging by a thread.

But there’s also an undeniable energy. A sense that Scotland isn’t giving up on itself. And that matters. That’s why I still write about Scotland from London. That’s why I’m still invested. That’s why the work of places like IPPR Scotland continues to resonate.

If Scotland can take what it heard at the conference (the honesty, the expertise, the lived realities), and actually act on it, the next decade could look less like “managed decline” and more like meaningful progress.

That’s a Scotland I’ll always root for.

(Aleisha Omeike is a trainee researcher with IPPR’s Migration, Trade and Communities team. Originally from Wishaw, North Lanarkshire, she currently lives in London.)