Apples and oranges? Scottish teachers’ pay in international context

Article

This is the first in a series of IPPR Scotland blogs as part of our project on Employment, Productivity and Reform in the Scottish Public Sector. This project is funded by the Robertson Trust.

Ongoing pressures on the Scottish government budget are firing debate about the public sector paybill. Is the public sector in Scotland unmanageably big? Are Scotland’s public servants unreasonably remunerated?

Inevitably, comparisons are made with pay and employment numbers in England. There are good reasons for this comparison: spending in England largely sets the envelope for public services in Scotland via the Barnett formula.

But if the question is what level of public services Scotland needs and how much we should pay for them, spending in England is not necessarily a good benchmark. Differences not reflected in the Barnett formula include demographic drivers of need (with Scotland’s relatively older population), variation in the cost –of-living (with the cost of living in remote and island areas between 14 and 30 per cent higher than elsewhere in the UK) and the scale of Scotland’s geography (one third of Britain’s landmass).

All of this means trying to understand Scotland’s public services, whether their costs are reasonable or excessive, simply by reference to spending in England is to take a very limited view. If the situation in Scotland needs higher spending on public services, political and policy processes should consider those needs, not just budgets, and make decisions accordingly.

Given the fact that the public sector is not monolithic, and that it delivers different things in different ways in different parts of the UK, we should be aiming to account not only for differences in cost but also in different cost-drivers. We need smarter comparisons. Let’s do that for teachers.

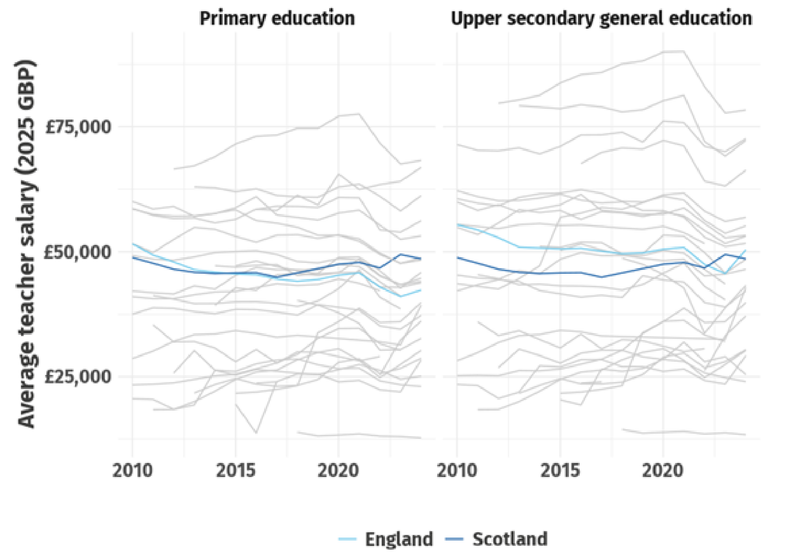

First off, we situate teacher pay and how it has changed in an international context. Across OECD countries teachers’ average salaries have been pretty stable over the past decade or so. Countries where teacher pay has been relatively low have seen increases, but in general the picture has hardly changed. There may be a gentle upward drift in primary school pay in OECD countries, but at the secondary level if there has been a consistent trend, it hasn’t been very strong. In this, Scotland is no exception.

Figure 1: Teachers’ salaries are similar in England and Scotland when compared with other countries

Average teacher salaries expressed in constant GBP using household final consumption purchasing power parities and UK CPIH

Data sources: OECD (salaries and PPP conversion), ONS (inflation)

Average pay in Scotland has increased relative to England, and while this has led to a gap opening up among primary school teachers, it has led to convergence at secondary level. But in an international context, what is striking is the similarity between pay in Scotland and England.

But is this the right comparison? Do teachers in different countries have the same job, given differences in education systems? Do some countries place higher demands on their teachers than others? While this is a multi-faceted issue, one clear dimension of it is the ratio of pupils to teachers - the higher this figure the higher teachers’ workload (more to manage during class contact hours, more correction and feedback etc.).

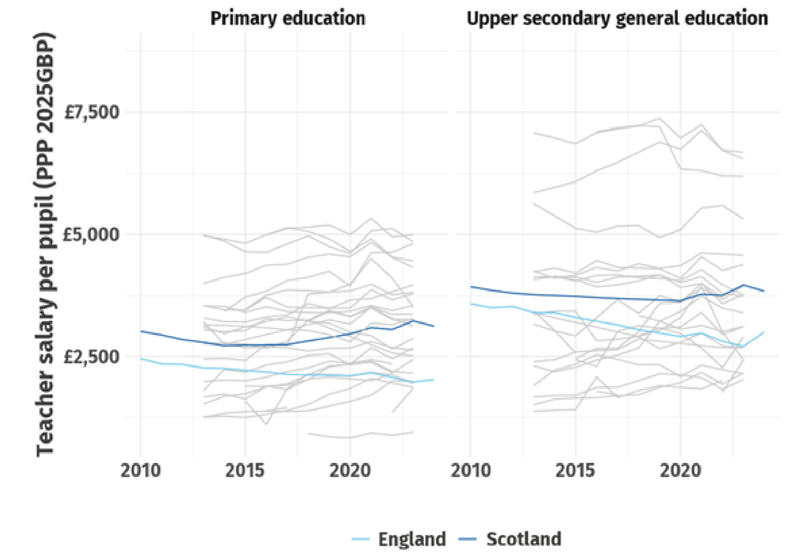

What does teacher pay look like if, instead of asking how well remunerated teachers are, we ask how much resource is put into teacher pay for each pupil who gets taught. While this is far from a sophisticated workload model, or a measure of the value produced in schools, it gets us closer than just considering what teacher salaries are.

Figure 2. Teacher pay per pupil in Scotland has broadly tracked international trends

Average teacher salaries per pupil, expressed in constant GBP using GDP purchasing power parities and UK GDP deflator

Data sources: OECD (salaries, PPP factors and international pupil/teacher ratios), HMT (GDP deflator), Scottish government (pupil/teacher ratio) and UK Department for Education (pupil/teacher ratios)

On this metric, a strikingly different picture emerges. The real terms cost of teacher pay per pupil taught fell in both Scotland and England in the opening salvos of 2010s austerity. In England this reduction has continued, going against the trend seen internationally for teacher pay per pupil to either hold steady or increase. In Scotland, the decline was reversed in the latter half of the 2010s and is now slightly higher. Secondary school teacher pay on this metric turned around as late as 2020, only recently reaching a similar level to 2010.

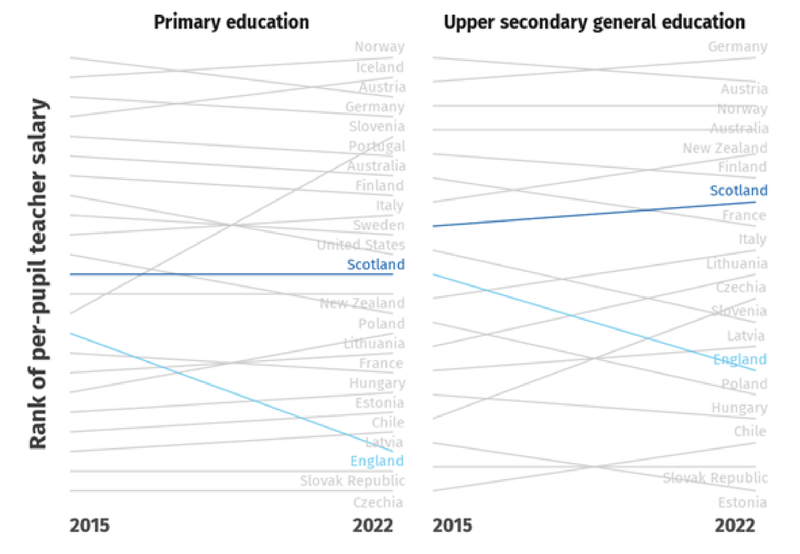

The difference can be seen more starkly if we compare Scotland and England’s ranking. Of 23 countries for which we have comparable primary school data, Scotland ranked twelfth in 2015 and remained in twelfth position in 2022. England’s ranking by contrast fell from fifteenth to twenty-first, with teacher pay per pupil higher only than Slovakia and Czech Republic. For secondary schools, where we have data for 19 countries, Scotland rose from eighth to seventh place while England fell from tenth to fourteenth.

Figure 3: The position of Scotland’s teachers in international ranking of pay per pupil has held steady, while England’s teachers have fallen back

Rank of average teacher salary per pupil taught, compared with PPP exchange rates, 2015 and 2022

Data sources: OECD (salaries, PPP factors and international pupil/teacher ratios), Scottish government (pupil/teacher ratio) and UK Department for Education (pupil/teacher ratios)

It is hardly plausible to interpret this pattern as showing teaching in England has become much more efficient than in other countries. Instead, the pattern suggests teacher pay in England, corrected for the amount of work expected of teachers, has fallen over the last decade. Indeed, concerns about wages and workload may be part of the explanation for what the National Education Union describes as “a teacher retention crisis, with England having among the worst attrition rates among developed nations.” In Scotland we see shown a slight increase in pay-per-pupil, consistent with international trends

For teaching, at least, this indicates the pressure in the Scottish government budget comes not from too much pay in Scotland, but too little in England.