Filling the funding gap: at what cost to Scotland’s public services?

Article

Last week the Scottish government published its delayed Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) which ‘provides the economic, funding and spending outlooks for the financial years 2025/26 to 2029/30’ and ‘the Government’s fiscal strategy to deliver sustainable public finances, within the current constitutional settlement’.

The MTFS was accompanied by a Fiscal Sustainability Delivery Plan which was preceded a week earlier by the Public Sector Reform Strategy.

The MTFS did not make for happy reading: it is forecast that by year 2029/30 there will be a resource funding gap of £2.6 billion and a capital funding cap of £2.1 billion. These are large figures. The Scottish government must balance its budget on an annual basis. Therefore, it’s understandable that concerns are growing for the future prospects of those who deliver public services and all of us who rely on them.

It is not our intention to discuss every aspect of the MTFS and associated papers in this blog. Rather, we offer some general comments relating to the ‘three pillars’ of public spending, economic growth and taxation around which the MTFS is constructed. The action mainly clusters around the public spending pillar but there is enough substance in the others to justify comment.

The economic growth pillar includes little that is new or interesting. Yet again it confronts us with the great paradox of SNP economic policy: that a Scottish government denied crucial economic powers (we are reminded that monetary and fiscal policy, employment law, non-devolved taxation and immigration are reserved) remains capable of generating transformational economic change (through, it seems, a range of relatively minor supply side interventions).

Some assertions in the paper might be generously described as optimistic (is Scotland a ‘high growth country’, for instance). More relevantly for this discussion, there is no attempt to explain how the various measures will lead to more rapid growth or to quantify the impact of higher growth on the public finances.

While we don’t wish to be unduly pessimistic, there are very sound reasons for Scotland’s public finances to be planned on the basis that the low rates of growth witnessed since the financial crisis will persist. The ageing society and shift to services have seen a lowering of growth rates in most advanced nations and the current geopolitical situation is hardly conducive to strong growth in a relatively small, open economy. Nothing in the MTFS or associated papers is likely to compensate for these factors.

The taxation pillar starts with the boast about “the distinctive and ambitious Scottish approach to taxation”. The approach is now certainly distinct from the UK but whether it is ambitious is highly contestable. And there is nothing in the MTFS or FSDP to signal a change in the level of ambition observed to date.

Indeed, the MTFS and FSDP include little new thinking further to the tax strategy published alongside the Scottish budget in December. The commitment to publish a literature review on wealth taxation is intriguing but there is no suggestion this is being treated with any sense of urgency. There is however a strong sense that the Scottish government does not believe that tax has a role in helping to fill the funding gap.

More disappointingly from IPPR Scotland’s perspective, all these papers combined do little to encourage a more mature conversation about devolved taxes in the longer-term.

Society is ageing, measures to address the climate emergency are becoming more urgent with every passing year and all the theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that the costs of delivering the labour-intensive services in health, care, education and policing will continue to rise at a rate above the whole economy rate of inflation. In these circumstances, it is reasonable to assume that taxes will have to rise in the longer term. Compared to the nations the Scottish government tends to hold as exemplars, the evidence is clear: the median Scottish taxpayer pays significantly less personal tax as a proportion of income.

The MTFS and FSDP presented an opportunity to start a mature long-term conversation about Scotland’s funding needs and how to pay for them. It is disappointing that this opportunity wasn’t taken.

But the main MTFS action is undoubtedly contained in the public sector pillar. It is here that the commitments are both significant and, in the context of recent Scottish administrations, somewhat original.

There is much to admire in the apparent strength of commitment to preventative spending. We strongly agree that a shift towards more preventative spending should reduce demand for ‘expensive acute or crisis services’ thereby contributing to fiscal sustainability.

But there has been a consensus on these matters since the Christie Commission reported in 2011. Yet progress has been glacial. What is perhaps most worrying is that there is no recognition in the MTFS that spending will almost certainly have to increase in the early stages of a serious shift towards a preventative approach. The reasonable assumption is that upfront investments in areas such as early years education will more than pay for themselves in the longer term. But these ‘invest to save’ measures must still be funded.

The Scottish government recognised as much through the introduction of its ‘Invest to Save Fund’ in this year’s budget. But a £30 million fund will not generate savings that touch the sides of a £2.6 billion deficit in four years’ time.

The most eye-catching commitment is the ‘Public sector workforce reduction target’. The plan is ‘for a managed downward trajectory for the devolved public sector workforce in Scotland (0.5 per cent per annum on average over the next five years)’. It is asserted that ‘frontline services will remain protected’ as the plan is implemented.

From the ministerial statement to the parliament, we learn that this reduction is to be achieved through natural attrition and recruitment controls. Is this really feasible? Natural attrition and recruitment controls will have to be managed very carefully to ensure that staff are matched with the delivery of government priorities. And while a blanket reduction in staff is unlikely to be easy to achieve anywhere in the public services – at least without a negative impact on service quality – it will be particularly challenging in areas like health and social care where we know demand will continue to rise.

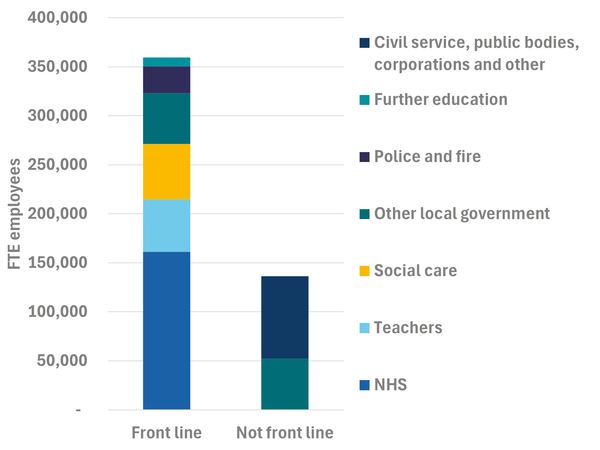

The 0.5 per cent per year reduction is across the whole of the public sector. If frontline services are protected, what does that mean for the parts that are not? Figure 1 shows a breakdown of public sector roles in areas devolved to the Scottish government. By far the biggest sector is the NHS, but other frontline services (teachers, police, fire officers, social care workers) are also significant.

Figure 1. Estimated FTE posts across the devolved public sector in Scotland

Source: Authors’ analysis based on the Medium Term Financial Strategy, the Scottish government’s 2024 Teacher Census, and Scottish Social Service Sector (2024) report on 2023 workforce data.

So, a 0.5 per cent cut to the overall public sector will need a much bigger proportionate cut to the non-frontline sector. How big? To estimate this, we assume a freeze in teaching staff across schools and colleges (despite Scottish government commitments to recruit 3,500 more teachers this parliament), as well as a standstill in the number of firefighters, police officers and frontline local authority staff. For health and social care, we assume the number of employees grows at the pace of our ageing society, around 1 per cent per year.1 Taken together, that would mean the rest of the devolved public sector facing staffing cuts around 3-3.5 per cent per year or a drop of about 13 per cent by 2029-30. That amounts to around 20,000 jobs.

Can the public sector backroom bear cuts of that scale? Does the distinction between frontline and backroom make any sense? What will cutting backroom roles mean for those operating at the frontline given that someone will have to pick up these tasks? Are there really thousands of backroom public sector roles that can be replaced by technology over the next four years?

The Scottish government risks finding out that the answers to these questions are unlikely to be the ones they need to achieve a pain-free balancing of the budget.