Skills passports: An essential part of a fair transition

Article

This month, government will publish its Clean Energy Workforce Strategy. This plan covers two aims. First, filling the growing demand for skills in clean energy industries is essential to keep on track to reach the government’s clean power targets by 2030. Second, having a coherent workforce plan is crucial to supporting workers in high carbon sectors like oil and gas to find new employment.

Declining North Sea reserves and low international oil prices, not net zero policies, are largely responsible for current job losses in oil and gas, but that is not stopping industry and political figures from attaching blame. This context makes the delivery of a tangible plan to support current and future workers, who may actually be impacted by decarbonisation, not only the fairest way to manage the transition but also the only way to maintain political support for the overall mission.

In this blog, we discuss how recent analysis of skills transferability between high and low carbon jobs must now progress to support for retraining, before setting out how genuine skills passports, funded retraining and a right to interview should all be considered within the upcoming workforce strategy as a tangible offer to workers and a means of retaining public buy-in.

The skills transferability drive

Renewable energy and fossil fuels are two sectors going in different directions. By 2030, the race to decarbonise the UK’s power sector could see the offshore wind industry supporting up to 90,000 jobs, up from around 40,000 today. By contrast, existing oil and gas fields in the North Sea are reaching maturity and it is becoming less profitable for companies to reach the final drops, all of which could see industry cutting up to 58,000 jobs by the 2030s.

This direction of travel has led to studies on the extent to which workers can move from high to low carbon jobs. This type of research is important for two reasons. First, many renewable energy developers are struggling to fills skills gaps and high carbon industries could be an important source of relevant experience. For example, research from Robert Gordon University suggests 90 per cent of workers in oil and gas roles have ‘medium to high skills transferability’ to closely related energy sectors like offshore wind. Indeed, in March this year, an assessment by the government’s Office for Clean Energy Jobs found that the majority of green jobs will need to be filled by the existing workforce, particularly from high-carbon industries.

Many renewable energy developers are struggling to fills skills gaps

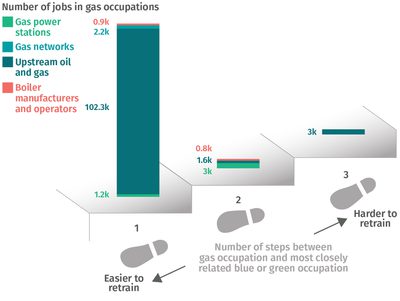

Second, it is important for workers themselves to understand what jobs they could move into in future. Crucially, from a worker’s perspective, this means knowing the full range of jobs that they could move into – and that range does not only include green jobs. As our own research shows, 93 per cent of workers have jobs that are very closely related to either jobs in clean energy industries or other jobs in a net zero world (what we call ‘green’ and ‘blue’ jobs in figure 1 below).

Figure 1: The vast majority of workers in high carbon sectors could retrain quickly into blue or green occupations

Histogram showing how related the closest blue or green occupations are to roles gas workers previously worked in where fewer 'steps' represents great similarity

Source: IPPR

Translating transferability analysis into training

But there is a missing piece in the analysis of skills transferability to date. While having an indication of low, medium or high transferability is a useful starting point, the next step is understanding how transferability translates into actual training. This is where skills passports come in. Or at least, where they were supposed to come in.

The original conception of skills passports was as a mechanism to identify and recognise some qualifications held by oil and gas and offshore wind workers as virtually equivalent to each other (with the potential to expand this recognition to other high and low carbon sectors in future). The intention was to reduce the time and money workers who move between sectors may have to spend taking unnecessary and duplicative training for skills they may already have.

The idea was first introduced towards the end of the Johnson government but faced delays. Several reasons have been suggested for this including:

- some oil and gas companies being less willing to engage in a scheme that involved helping workers move out of their sector

- some certification bodies being reluctant to see a fall in revenue that would come from reducing training needs

- industry concern about the importance of recognising the differing in health and safety training requirements between industries

- political instability and uncertainty leading to poor coordination to address these barriers.

Since the Labour government took office, there has been a renewed effort to get skills passports back on track and in January this year a digital platform was set up that invites workers from both oil and gas and offshore wind to upload information about their skills into a database. This database then provides an analysis of the skills gaps they would need to fill to apply for a number of roles listed by the platform.

Designing a genuine skills passport

Though it is called a ‘skills passport’, this platform is only seen by government as phase 1 of the original intention of the skills passport, with the potential for further commitments in the upcoming Clean Energy Workforce Strategy.

We are considering ways to design a genuine skills passport that reduces training time and costs for workers, and introduces a ‘right to interview’ (detailed below) that could give a smoother route to finding new employment as they move out of high carbon industries. We envisage a genuine skills passport to involve four components.

1. Building a skills database

As discussed above, a skills database that enables workers to upload their skills and analyses what gaps they have is what already exists. It is what the industry call a ‘skills passport’ (the language is a little unhelpful). There are plans to expand the number of potential roles listed on the platform in offshore wind and the number of sectors workers could move into (eg CCS and hydrogen).

A skills database is a critical component for workers to understand what skills they may still need to move into a particular role, and for businesses to understand how many workers have skills they need.

2. Meriting

Meriting is closer to what proponents actually think of when talking about skills passports. Meriting is the industry term for recognising existing skills that workers have and reducing the length of a training course that a worker may need to take to avoid unnecessary duplication. The time saving here isn’t the major benefit, however, the cost saving could be substantial.

3. Funding

Retraining from high to low carbon jobs will need funding to incentivise and support workers. The government recognises this and is making progress on. For example, it recently announced a £900,000 Oil and Gas Transition Training Fund to trial support for 200 oil and gas workers in Aberdeen as well as £1 million each in Cheshire, Lincolnshire and Pembrokeshire for regional skills pilots.

Retraining from high to low carbon jobs will need funding to incentivise and support workers

However, more is needed. For example, as we have previously called for, a Training Fund that supported every worker that could be affected by decarbonisation could require an annual investment of approximately £1.1 billion for 10years. Even starting with the estimated 211,500 most at-risk or in-demand jobs in the oil and gas sector, gas networks and gas heating, a scheme that scaled up from the trial support in Aberdeen could require around £272 million of investment per year between now and the end of the parliament.

4. A right to interview

IPPR has previously recommended the government introduce a ‘right to interview’ for new roles to deliver a fair transition for workers. This could be introduced as a specific employment right or be a point of negotiation between trade unions and industry stakeholders. Either way, once a worker has used the skills database (step 1), identified the gaps in their training and has benefited from a shortened (step 2) and funded (step 3) training course after using the database, introducing a right or guarantee to interview could represent a tangible offer to workers by speeding up the time to find a new role.

Options for implementing a right to interview could include the following.

- Requiring developers to agree to workers’ rights to an interview for certain roles as a condition of CfD auctions – while we appreciate conditionality over domestic content has some opponents, a right to interview could be more popular with offshore wind developers. A platform of workers who can demonstrate they have the right skills for certain offshore wind roles could help reduce search costs for those looking to hire.

- Voluntary agreements whereby developers agree to recognise worker’s rights to an interview – this option may reduce the number of job options available to workers as some industries may be slower than others to recognise the right to interview.

- Primary legislation – this option could see the right to interview applied to multiple sectors but would take longer to implement as it would require more extensive consultation. The Department for Business and Trade would also need to introduce the legislation and coordinate with other departments.

Conclusion

The upcoming workforce strategy is a sign that the current government is taking skills planning and support for workers in high carbon industries seriously and recognises the political attacks it is already facing and will continue to face in future. To ensure it retains public buy-in, the government should consider genuine skills passports, funded retraining and a right to interview, all of which taken together could provide a tangible package of support for workers, while meeting the growing skills demands necessary to delivering the government’s clean power mission.

Related items

Resilient by design: Building secure clean energy supply chains

The UK must become more resilient to succeed in a more turbulent world.

A people-focussed future for transport in England

Our findings from three roundtables on the impact of transport in people’s lives and the priorities for change.

The sixth carbon budget: The first plan without consensus

For decades, UK climate action was cross-party, and consensus meant policy looked different to politically competitive issues like tax.