Reclaiming Britain: The nation against ethno-nationalism

Article

How can progressives respond to the increasing ethnonationalist narratives of the political right?

Last summer, after the most widespread racist rioting since 1919, IPPR wrote it was “a testament to progress” that deporting black and brown people living in Britain, the response to those past riots, was no longer a palatable policy option. 18 months later, that looks naïve.

We have seen an alarming turn on the right towards policies of mass deportation. Reform are prepared to deport 600,000 people, while the Conservatives have pledged to remove 750,000. Both are ambiguous about the extent to which long-term and even lifelong residents with legal rights to live in this country will be affected. Just as troubling is the shift in the ideas behind the policy. It is now common to hear anti-migration politics articulated in terms of ‘cultural coherence’ and inherited difference, including by those who not-so-long-ago based their arguments on scarce jobs, houses and public services.

Meanwhile, this autumn saw the largest far-right demonstration in British history, animated by a growing fear that “we are being colonised by our former colonies”, and hate crime is rising again.

a view of the national community defined in ethnic terms and society as a hierarchy is stirring fear, anxiety and anger in people of all backgrounds

We should be clear about what is happening here: large parts of the political right are increasingly, often explicitly, ethnonationalist. No longer consigned to the fringes of British politics, a view of the national community defined in ethnic terms and society as a hierarchy is stirring fear, anxiety and anger in people of all backgrounds. But it is also changing the terrain of political contest, and redefining for the left is for.

Since the 1990s, progressives enjoyed considerable success in disentangling the politics of nation from the nationalist right, offering more inclusive visions of community and belonging. Today, those achievements are under attack. Used to opponents who challenge them mainly on grounds of economic equality, progressives now find themselves locked in conflict with those who reject far more basic tenets of human equality.

there has been a notable rise over the past two years in the number of people who think being ‘truly British’ is something you are born with rather than something you can become

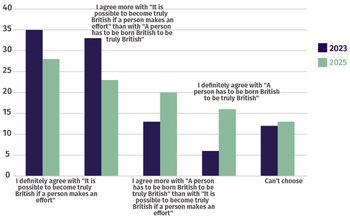

So far, progressives have struggled to match the right’s ideological entrepreneurship. Actors from Nigel Farage and Robert Jenrick to Tommy Robinson and Paul Joseph Watson have proved adept at consistently connecting the grievances of “white British” people to those who are not. In doing so, they are deliberately trying to remould the nation from a civic community to an ethnic community in eyes of the public. They may be having some impact. Although it remains a minority view, there has been a notable rise over the past two years in the number of people who think being ‘truly British’ is something you are born with rather than something you can become (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: A rise in an ethno-nationalist conception of British identity

Share of people who believe “It is possible to become truly British if a person makes an effort” compared to “A person has to be born British to be truly British”

Source: Authors analysis of IPPR-YouGov 2025; British Social Attitudes 2023

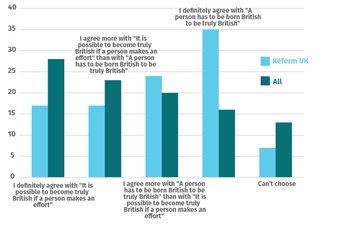

Figure 2: A majority of Reform supporters are ‘ethnic’ nationalists, while a majority of supporters of all other parties are ‘civic’ nationalists

Share of people who believe “It is possible to become truly British if a person makes an effort” compared to “A person has to be born British to be truly British”, by voting intention in December 2025

Source: Authors analysis of IPPR-YouGov 2025

This is a short period of time for so many people to have changed their fundamental outlook. Indeed, when people are asked about civic and ethnic conceptions of nationhood independently, rather than in comparison, we observe less shift in public opinion. What we are therefore likely seeing is that people with long-standing but weak ethnonationalist sympathies have been authorised and actively encouraged to express them with greater conviction, whether in a survey, on social media or on the streets. The norms that usually deem prejudice and far-right views as unacceptable are being rapidly eroded by a new group of right-wing politicians and online activists, who are changing society from the top down.

Political contest is changing, and progressives need to change with it. For a generation of politicians who have only known the post-Cold War era, the idea that moral arguments about equal human worth have to made, and are not given, is bewildering. But that is what must happen. As ethnonationalism re-emerges as a defining characteristic of the right, in Britain and around the world, equality must return as the distinguishing feature of the left. Not in the shape of what was, but as a new politics of common life, grounded in moral arguments about what could be.

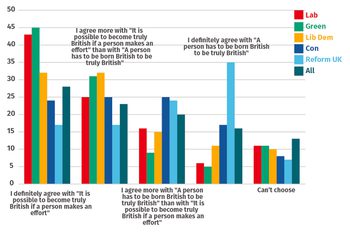

most Britons continue to prize universalist, civic behaviours and resist narrow, nativist ideas of community

The challenge is to tell another story of who we are, with a forward sense of the collective project. The revival of nationalist politics has to be superseded, rather than simply cast aside. There are resources of hope to build a new collective politics from: most Britons continue to prize universalist, civic behaviours and resist narrow, nativist ideas of community (figure 3).

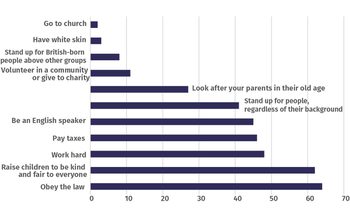

Figure 3: People overwhelmingly prioritise universal over exclusive ideas of citizenship

Share of people who believe the following are important qualities to have or things to do in order to be a good British citizen

Source: Authors analysis of IPPR-YouGov 2025

In that context, the prime minister’s speech to Labour Party conference in September 2025 was a positive step forward. The government’s apparent reticence gave way to a willingness to contest the idea of the nation: to name the ethnonationalist threat and declare a ‘battle for the soul of the country’. He invoked everyday expressions of mutuality, dignity and collectivism in modern Britain and encouraged broad-based participation in the national project in opposition to the right’s evocation of a broken, divided country in need discipline and punishment.

But this has not yet been matched by serious follow-through, and our findings suggests progressives are conceding ground. Animating an alternative vision of nation cannot be outsourced to a few speeches or policies. It must span every area of government policy, underpinned by a radical re-imagination of the nation state.

A nation-building project

“National pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals: a necessary condition for self-improvement”, wrote the American philosopher Richard Rorty. In Britain, pride is falling (figure 4), and a belief in advance is giving way to decline. A growing number of people think about the future mainly as worse than the present. They worry that they and their children will not be better off; that new technologies will take good work away; that crime will rise and society degenerate in some way, all while the spectres of a war-torn world, climate breakdown and the next crisis hover overhead. More visibly, high streets and community buildings in decay, long queues for public services, people seeking asylum in holiday hotels and the increased visibility of low-level crime and anti-social behaviour is contributing to a sense of malaise and fatalism.

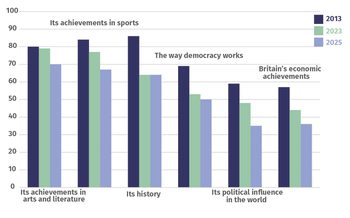

Figure 4: Pride in Britain has declined

Share of people who are proud of Britain in the following things

Source: Authors’ analysis of IPPR-YouGov 2025; British Social Attitudes 2023

For progressive politics, fatalism is toxic. Progressives rely on the claim that the future depends on what we do together, and that society can be always be improved in a number of ways. When the future looks set, and decline feels inevitable, people will retreat from democratic politics or look for a radical break from the present. The contemporary right thrives on decline and the sense that democratic politics cannot avert it.

we have much more say over our collective destiny than they want us to think. A commitment to collective action resounds in the history of the left’s greatest achievements.

But we have much more say over our collective destiny than they want us to think. A commitment to collective action resounds in the history of the left’s greatest achievements. The task of nation-building today is simply to recover faith in our capacity to shape what lies ahead.

The politics of nationhood has always been a difficult concept for progressives. There is a basic difficulty in knowing which ‘nation’ we are talking about at a given time (the United Kingdom, Great Britain, or their constituent parts?). Moreover, legacies of colonialism, empire and racial exclusion hang heavy in nationalism’s difficult history.

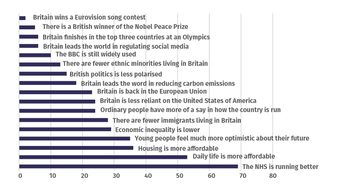

But nationalism has always been capable of progressive and reactionary expressions: it can look backwards to pre-modern identities or forwards to democratising and egalitarian goals. When asked what would make you proud of the country in a decade’s time, Britons’ overwhelmingly choose broad-based, progressive objectives like healthcare, affordable living and lower economic inequality over ethnic solidarities and reactionary expressions (figure 5).

Figure 5: There is latent desire for a universalist, redistributive, civic-egalitarian politics

Share of people who say the following would make them most proud of Britain in 10 years’ time

Source: Authors analysis of IPPR-YouGov 2025

Progressive politics rests on the ability to forge identification with the collective. The nation is the largest unit at which democratic accountability can meaningfully operate and, for many people, it is the unit with the deepest cultural and emotional roots. The nation, almost uniquely, can marshal an evolving, shared understanding of our past and present, and project forward into a future that can be built through collective effort.

It remains the site where democracy is most able to shape markets and discipline capital. And so long as democracies are organised along national lines, national solidarity is an essential precondition to support for tax and redistribution. Willingness to pay tax rests not only on a sense of our own self-interest but a sense that we are part of a greater whole. The NHS for instance has achieved deeper cultural roots than the rest of the welfare state precisely because it is tied to people’s sense of national identity, as a result of a deliberate effort at ‘cultural embedding’ in the years after the second world war.

To leave the question of the nation to the right at this particular moment is profoundly reckless.

Whether progressives wish it or not, what the nation stands for and who falls within its membership is being deeply contested. If progressives do not imprint their values on the nation, then only their opponents will. To leave the question of the nation to the right at this particular moment is profoundly reckless.

Whatever we define ourselves as, by race or religion, or the town we live in and job we do, there is always a part of us that is more than that. That is what makes us alike and what progressive politics must make more salient. If there were no point on which separate interests coincided, society could not conceivably exist. It is precisely on the basis of this common cause that society should be governed.

Progressives have to start with clarity about the story they wish to tell about the country, grounded both in pragmatic public opinion – which continues to prize universalism over particularism (figures 3 and 4) – and an idealistic vision of what the country can be.

This isn’t a question of reinventing the wheel; the raw materials of such a story are readily available. It could start by reframing what people are already doing as part of a collective national project. When we pay attention to our children’s school performance or our parent’s health, apply for a new job or return to work, start a company or organise in a trade union, we are acting pragmatically in our own interests. But we are also acting in the national interest. The progressive governing agenda can then be described as society’s part of the bargain in the reciprocal commitment with individuals: to make sure there are good schools, good healthcare, good jobs and investment opportunities, and so on.

A progressive nation-building project should face the future, where the right’s nation-restoring project looks to the past.

And while trust in elites is badly tarnished, support for shared national institutions like the NHS, the BBC and parliament remains strong. The struggles that produced these institutions are a proud part of our history, but also a reminder that democracy is a continual, unending process of maximising our individual and collective agency over arbitrary and oligarchic concentrations of power.

The government could narrate its own agenda as part of that same tradition and project of collective endeavour. Indeed, many of its policies are distinctly in keeping with a universalist, redistributive, civic-egalitarian politics: £725 billion investment in public infrastructure, bringing passenger train operators and British Steel under public ownership, creating a publicly owned energy company, setting up the National Wealth Fund, subsidising and supporting eight nationally strategic industries, removing obstacles to building, rebuilding social infrastructure through the Pride in Place initiative, raising tax, expanding free childcare and school meals, attempting to abolish the gig economy and raising the wage floor.

The right claim to own the concept of national interest and define it in narrow, nostalgic terms. This can be contested, both in terms of who owns it and how it is construed, to incorporate public services and ownership, national industry and tax. A progressive nation-building project should face the future, where the right’s nation-restoring project looks to the past. It should take on the challenge of unifying and universalising concerns, with a reflex to reframe contentious differences as common cause, from tax and welfare to immigration and culture wars. This is how progressives construct new majorities in a time of plural antagonisms.

But ‘narrative’ is never enough; it is wrong to assume this is all progressives lack in the current moment. When policies do not add up to a project, it is because they are not bound by a set of defining and guiding ideas, interacting so the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts.

The work of nation-building comes down to two things: binding the people into a nation and translating the nation into a state.

A Decade of National RenewalA return to the ideas in the prime minister’s speech in September would be a valuable starting point. The government should extrapolate these into a coherent programme of social, economic and democratic reform for the decade ahead. It is easy to dismiss the development of a medium-run vision to something ornamental, secondary to electoral prospects and hard-headed ‘delivery’, but it is precisely the pairing concrete short-term demands with long-term causes that gives people reason for sustained commitment.

The work of nation-building comes down to two things: binding the people into a nation and translating the nation into a state. The former requires deliberate efforts to join up policy agendas on citizenship and immigration, communities and place, public infrastructure and ownership, media reform, the national curriculum, culture and the arts. The latter requires a view of the state not only as a share of GDP or as simply the delivery mechanism for public services, but as an organ of collective decision-making: a state that instigates and distributes economic growth, sets rules that share power and dignity, and builds and renews institutions for the common good. That will require new thinking about the correct relationship between states and markets, constitutional reform, tax and the welfare state, and a strategy for navigating a world of great power politics.

Over the next year, IPPR's Decade of National Renewal programme will be publishing new thinking in all these areas. A new age demands a new left. That requires progressives grasp the profound changes reshaping economies and societies, the threats and the new possibilities, and approach them with that rarest of commodities: political imagination.

Related items

Dr Parth Patel on BBC Politics Live, discussing the economy, welfare, Kemi Badenoch, and Reform

IPPR research on adult social care on ITV News

Progressive renewal: The Global Progress Action Summit

A quarter of the way through this century, change is in the air. Everyone, everywhere, seemingly all at once, wants out of the status quo.