Why clean energy, not new oil and gas, will deliver energy security, lower bills, and the jobs of the future

Article

The energy trilemma – the need to balance reducing emissions with energy security and affordability – is often used as a stick to beat climate policy with. Following Labour’s commitment to end all new oil and gas licenses, this has never been more apparent. Newspapers and politicians have lined up in a coordinated attack on the grounds that it would threaten energy security, push up bills, and lead to job losses.

In reality, the trilemma is now a false dichotomy (or trichotomy). The world we are now living in means the best answer to every line of attack that we’ve seen recently is more ambitious climate policy, not less.

In this article, we set out why ending new oil and gas developments combined with more ambitious policies to rollout clean energy is by far the best path to addressing every aspect of the energy trilemma.

Let us assess the specific criticisms around perceived threats to energy security, bills, and jobs in turn.

"a more ambitious rollout of renewables is by far the best of way reducing oil and gas imports"

The fastest route to energy security is an accelerated rollout of renewables

New oil and gas developments will have a minimal impact on supply. In 2021, 77 per cent of oil and 21 per cent of gas produced in the UK was exported (NSTA 2023; DUKES 2022). New oil and gas fields will not only follow similar percentages but 70 per cent of what’s left in the North Sea is oil, not gas, meaning the vast majority of these new sources will be exported (Uplift 2022).

New oil and gas fields also do nothing to solve the current energy crisis. New oil and gas fields typically take up to 28 years to start producing (Dunne 2023), by which time the UK will theoretically have already reached its net zero targets and dramatically decreased its oil and gas consumption.

"offshore wind, onshore wind, and solar PV have been substantially cheaper than gas used in power stations in recent years"

Moreover, new IPPR analysis shows that a more ambitious rollout of renewables is by far the best of way reducing oil and gas imports. In figures 1 and 2 below, we compare two scenarios looking at future oil and gas imports. In the first scenario, the UK develops new oil and gas fields with only moderate ambition on renewables. In the second scenario the UK ends new oil and gas fields and follows the CCC’s ‘tailwinds’ scenario, a more ambitious policy pathway which places more emphasis on technologies like offshore wind, onshore wind and solar PV and less on gas. Beyond this scenario, analysis by Ember presents an even more ambitious scenario that sees the power sector fully decarbonised by 2030 with almost no use of gas in power stations, suggesting imports could be decreased even further Brown et al 2022 (see Appendix for breakdown of technologies by scenario).

The result from our analysis is a 12 per cent decrease in oil imports and a 17 per cent decrease in gas imports in the ‘tailwinds and no new development’ scenario compared to developing new oil and gas fields. In short, the best route to energy security is a rapid rollout of clean energy.

Figures 1 and 2: Both oil and gas imports are much lower with greater climate ambition and no new oil and gas than moderate climate ambition and new oil and gas fields

Projections for oil and gas imports over time comparing ‘balanced’ CCC pathway with new fields and ‘tailwinds’ CCC pathway with no new fields

Sources: IPPR analysis of NSTA 2023; DUKES 2022; CCC 2020

Accelerating the deployment of renewables is the best way of cutting energy bills

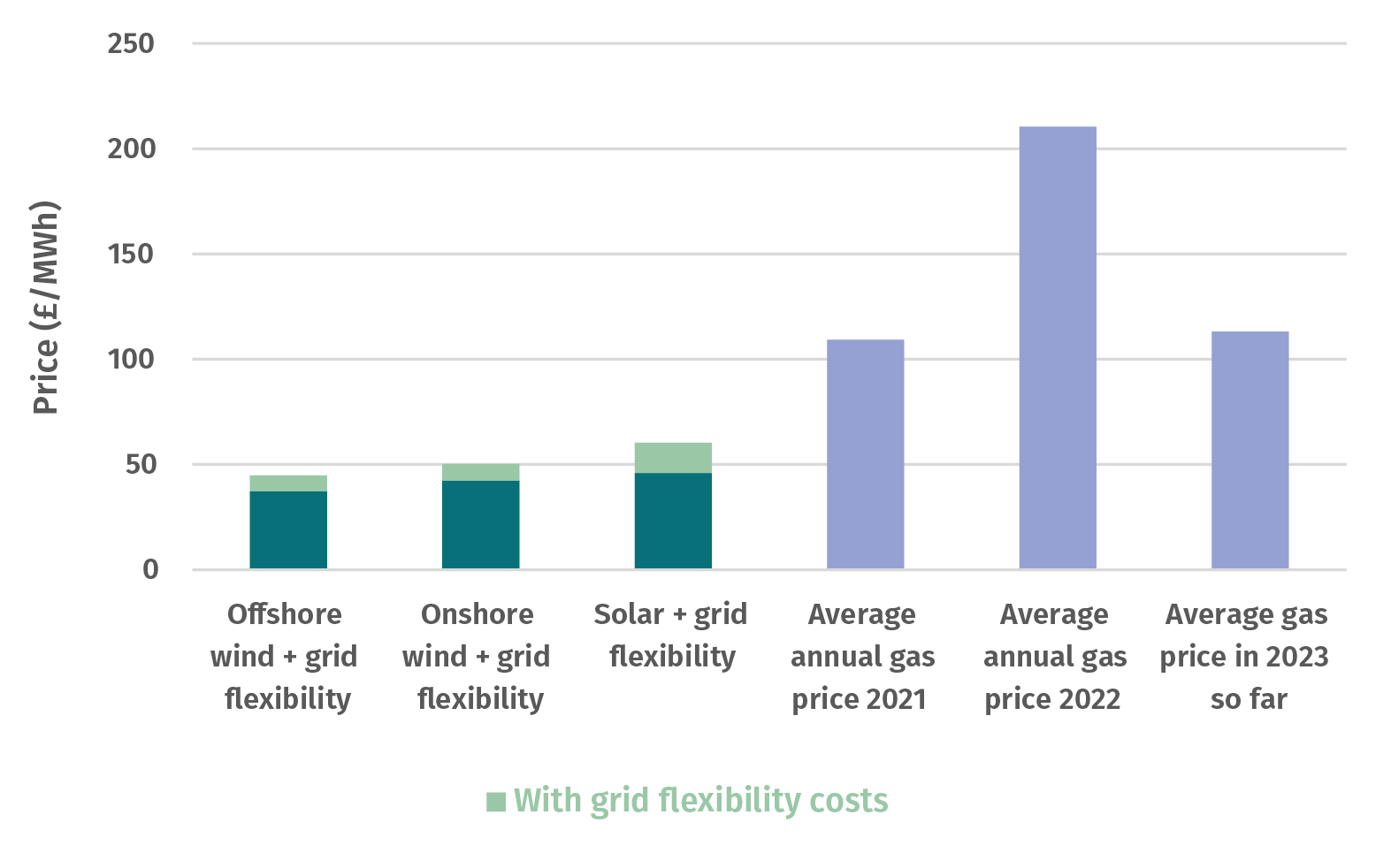

Accelerating the deployment of renewables is also the best way of reducing energy bills in two ways. First, as figure 3 shows, offshore wind, onshore wind, and solar PV have been substantially cheaper than gas used in power stations in recent years, even when adding the system cost of the grid flexibility needed to smooth out renewable intermittency. Accelerating the rollout of renewables will help to bring bills down further and displace more expensive gas from the system.

By contrast, increasing oil and gas production does very little to reduce energy bills since prices are set by international, not local, markets, a point which is echoed by the former Energy Secretary (Kwarteng 2022). Consequently, not only would new oil and gas fields provide very little increase to domestic supply of oil and gas as mentioned above, the UK would also continue to pay a high global market price.

Figure 3: Renewables are currently much cheaper than gas even when including the cost of system flexibility

Cost comparison of renewable technologies to average annual gas prices

Sources: IPPR analysis of Nordpoolgroup 2023; BEIS 2022; Strbac and Aunedi 2016

"Not only would a faster rollout of low-carbon heating and energy efficiency decrease energy bills now but, as the power sector increases its proportion of cheap renewable electricity generation, it will protect households from any future price shocks and lead to lower bills in the future too."

Secondly, accelerating the transition towards energy efficient, renewably heated homes could also substantially reduce energy bills, particularly with current gas prices so high. Previous IPPR analysis shows that installing electricity-consuming heat pumps, good quality insulation and ventilation measures as part of a whole-house approach could lead to savings of up to £430 on energy bills for the average home compared to the tariff set by the April energy price guarantee (Emden 2022; Evans 2022).

Not only would a faster rollout of low-carbon heating and energy efficiency decrease energy bills now but, as the power sector increases its proportion of cheap renewable electricity generation, it will protect households from any future price shocks and lead to lower bills in the future too. The faster this happens, the faster energy bills will come down. In short, the best way to reduce energy bills is climate leadership.

A green industrial strategy protects workers better than new fields

The last critique made against a policy of no new oil and gas licenses is that it could threaten jobs. Yet the oil and gas sector is notorious for insecure work and further extraction and exploration would continue a history of volatile hiring and firing. For example, in 2009, the sector employed 300,000 workers in the UK.

Over just five years the sector saw increases of over 50 per cent with a peak of 470,000 employed in 2014. But by 2019, as a result of the oil price crash in 2014/15, all these gains were lost with employment levels returning back to around 300,000 jobs (OGUK 2019). Perhaps unsurprisingly, a previous survey of oil and gas workers confirmed that four in five workers would consider moving out of the sector with 58 per cent of workers citing job security as their top priority (Jeliazkov et al 2020).

Importantly, the future of oil and gas production in the UK will have an impact on workers, but this will happen whether or not new oil and gas fields are developed. This is because the North Sea is a mature basin meaning that most of its production is already in decline. According to North Sea Transition Authority projections, new oil and gas fields being developed would do very little to impact this trend.

The good news is that a robust green industrial strategy, designed well, could create hundreds of thousands of jobs, many of which will require the kinds of skills that many oil and gas workers already have. As previous IPPR research shows, 1.6 million jobs could be created in the net zero transition over the next decade, including in sectors like offshore wind, decommissioning and subsea network projects for which workers in oil and gas sectors have transferable and in demand skills (Emden et al 2020).

Ultimately, what matters most to ensuring workers are treated fairly is a long-term plan that commits to a managed phase-out of oil and gas, specifies the technologies of the future, and details both the support for workers to move between sectors (such as support with retraining and travel expenses) and guarantees future high-quality, stable employment. In a survey this year of over 1,000 oil and gas workers, where they were asked to co-develop a set of demands to government, their top two demands were to put workers at the centre of transition planning and provide clear, accessible pathways out of high-carbon jobs (Harris et al 2023).

"the best way to protect jobs is through a faster clean power rollout, a robust green industrial strategy, and a genuine commitment to a fair transition plan for workers"

In this respect, both the recent announcements to increase exploration and the North Sea Transition Deal – a loose agreement between industry and government to transition the sector towards a net zero future – do nothing to address the insecurity of current work. Indeed, by failing to commit to a long-term plan for the North Sea built on the foundation of clean power, they exacerbate the problem as workers remain trapped in a bubble of insecure work.

Research from Carbon Tracker suggests that if new oil and gas fields go ahead, oil and gas companies are at a higher risk of investing in ‘stranded assets’ that become uneconomic when demand for oil and gas falls (Prince 2022). In short, the best way to protect jobs is through a faster clean power rollout, a robust green industrial strategy, and a genuine commitment to a fair transition plan for workers.

Greater climate ambition solves the energy trilemma more effectively than new oil and gas even if there was no climate crisis

You may note at this stage that none of these arguments in favour of greater ambition on renewables and an end to new oil and gas fields mention the obvious incompatibility of increased production with net zero targets. Recent analysis from Uplift shows how the emissions produced from consuming new barrels of oil and gas extracted in the UK will exceed the combined total annual emissions from the 28 poorest countries in the world. Even for the much smaller amount of oil and gas we will continue to need in future, the CCC suggests that the industry’s target to reduce emissions from the production process by 50 per cent by 2030 falls “well short” of the 68 per cent reduction which should be achievable in that time (CCC 2022).

Yet even though new oil and gas fields’ incompatibility with future net zero targets is obvious, the overarching point of this piece is to show that more ambitious climate policy is the most important solution to every aspect of the trilemma, even if the UK didn’t have a net zero target and even if climate change didn’t exist.

Showing climate leadership is the best way of improving energy security, the best way of reducing energy bills and, combined with a green industrial strategy, the best way of securing good, quality jobs for workers.

Joshua Emden is a senior research fellow at IPPR.

Notes

Table 1: Breakdown of major technologies in the power sector by scenario in 2030 (TWh)

Technology | CCC Tailwinds (2030) | CCC Balanced Pathway (2030) | Ember analysis (2030) |

Bioenergy and waste | 5.1 | 4.5 | 14.1 |

Bioenergy with CCS | 7.4 | 3.6 | 5.7 |

Gas unabated | 23.2 | 32.0 | 2.5 |

Gas with CCS | 20.1 | 39.0 | 1.9 |

Nuclear | 49.7 | 59.0 | 56.9 |

Hydrogen | 3.1 | 3.1 | 12.2 |

Offshore wind | 167.9 | 164.0 | 145.3 |

Onshore wind | 51.6 | 36.9 | 66.1 |

Solar | 30.1 | 22.7 | 44.2 |

Marine and hydro | 6.6 | 16.6 | 10.9 |

Sources: IPPR analysis of Brown et al 2022; CCC 2020