A defeat to reckon with: On Scotland, economic competence, and the complexities of Labour's losses

Article

Labour is in shock. The party may not have expected to win an overall majority on 7 May, and might even have been surprised if it had come first in seats. But it certainly did not anticipate ending up with fewer seats than it had five years ago, and thereby being left without any prospect of being able to negotiate its way to power via deals and understandings with smaller parties.

One advantage of this shock is that the defeat is being taken seriously. It has been described as the party's worst result ever, and has even led some to question the party's long-term future. However, shock also has its disadvantages. Faced with trying to account for the unexpected, there is a tendency to grab the first plausible answer that comes along, and particularly to resort to explanations that accord with existing preconceptions of how the party should comport itself. For example, in his instant commentary on the defeat, Tony Blair argued that the party needs to return to the 'centre ground' and show that it is for 'ambition and aspiration'.

But if one thing is clear about this election, it is that the temptation to look for one single straightforward explanation or response should be resisted. After all, its outcome marked the final death-knell of the idea that there is such a thing as a single Britain-wide electoral contest. There was, in truth, one election outcome in England and Wales and another very different one in Scotland. Both outcomes have to be taken on board if an adequate response to Labour's electoral woes is to be identified.

Recovering Scotland

Of these two outcomes, easily the more catastrophic as far as Labour is concerned was the one in Scotland – yet it also appears to be the one that is at risk of being ignored. Because the results north of the border mean that the parliamentary Labour party is all but denuded of Scottish voices, the initial manoeuvres in the party leadership contest are being played out exclusively among MPs from England and Wales, many of who are relatively unfamiliar with the party's difficulties north of the border.

However, there is little prospect of the party regaining power unless the party recovers at least some of the ground that it has lost in Scotland. If the SNP were to again secure the 50-per-cent share of the vote that they won on 7 May 2015, Labour would – assuming a uniform swing from Conservative to Labour in each and every constituency – need to be as much as 12.5 points ahead of the Conservatives nationally in order to secure an overall majority; Labour would need to be nearly four points ahead just to become the largest party. Moreover, these figures take no account of the review of parliamentary boundaries that we can now expect to take place, and which will reduce the disparities in the size of constituencies that currently work to Labour's advantage.

It is true that, in part, the defeat in Scotland can be regarded as sui generis. By the time that polling day approached in May 2015, nearly nine-in-10 of those who voted 'yes' in the independence referendum in September 2014 – among them some two in five of those who voted Labour in 2010 – had opted to back the SNP. The constitutional question has become central to Scottish electoral politics to an unprecedented degree. Labour is confronted with the unenviable challenge of persuading those who want to leave the UK to support a party that takes the opposite view, but at least this is a specifically Scottish dilemma that has few immediately obvious implications for the strategy that the party should adopt in the rest of the UK.

However, this is not all that lies behind Labour's difficulties in Scotland. The party has also been outflanked by the SNP on the left. The referendum gave the SNP an opportunity to outline the kind of Scotland that it wished to create, and part of its vision was that independence would make it possible to create a more equal society. That message hit home. Data from the British Election Study shows that those who voted Labour in 2010 but subsequently switched their support to the SNP after the referendum were both disproportionately in favour of a more equal society and more likely to regard the SNP as the party that shared that view. No less than 74 per cent of these lost voters supported the redistribution of income (compared with 59 per cent of Scots generally), and although 48 per cent of them thought that Labour backed that position, 75 per cent reckoned that the SNP did.[1]

This evidence must caution against any idea that the solution to Labour's problems is simply for the party to reclaim the centre ground of British politics that was supposedly vacated during Ed Miliband's tenure as leader. The complaint about the party north of the border has been that its voice has not been sufficiently radical, or at least distinctive – an impression that fighting a referendum campaign in alliance with the Conservatives certainly did nothing to dispel.

The demography of defeat: age and class

But what of the rest of Britain? While Labour may not be capable of winning the keys to 10 Downing Street without Scotland, it certainly cannot win them on the back of Scottish votes alone. How should we understand the party's failure south of the border?

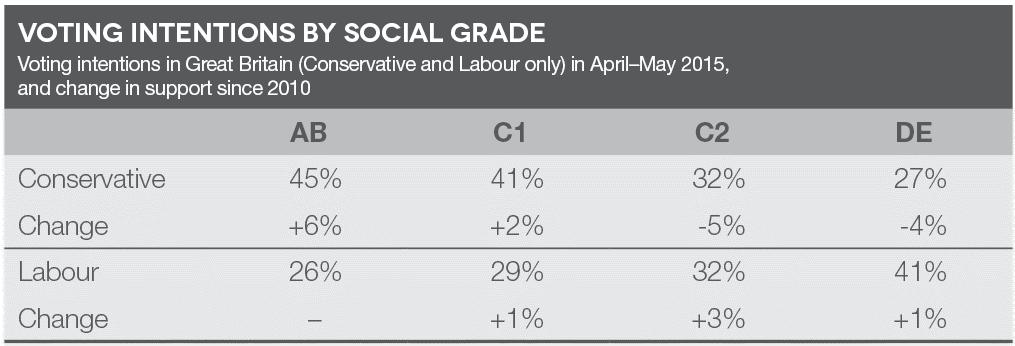

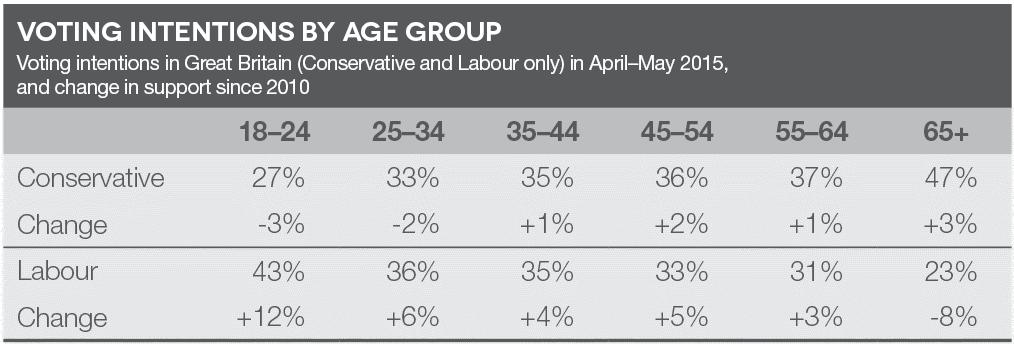

Let us begin with a little demography. After each election, Ipsos MORI publishes a demographic breakdown of how people said they intended to vote during the election campaign, based on all of the polls they conducted during that period. Tables 1a and 1b includes extracts of their analysis for 2015. We should note, crucially, given the errors in the polls, that the data has been weighted so that overall it reflects the actual outcome of the election. Ipsos MORI's figures are broadly corroborated by a large (over 12,000) poll of how people actually voted that was conducted on polling day by Lord Ashcroft[2] – an exercise to which we will return below.

Table 1a

Table 1b

Source: Ipsos MORI (2015) 'How Britain voted in 2015: The 2015 election – who voted for whom?', published 22 May 2015, based on fieldwork carried out 10 April–6 May 2015.

It comes as little surprise that the Conservatives were more successful among middle-class AB and C1 voters than among less affluent working-class C2 and DE voters, and that the reverse is true for Labour. These figures in themselves tell us nothing about whether Labour was particularly unsuccessful in 2015 among what might be regarded as relatively 'aspirational' voters. However, what we can observe is that the difference between classes in terms of their support for the Conservative party widened. Support for the party increased somewhat among AB and C1 voters, while it fell back among C2 and DE voters. This would appear to suggest that Labour did indeed lose touch with vital middle-class support.

Yet we have to be careful. The obverse pattern to that of the Conservatives is not found in the pattern of Labour's vote. The level of support for Labour in each class was much the same as it had been five years previously. There is, in truth, no strong evidence here of Labour particularly losing touch with its more middle class supporters. Rather, what is notable about the party's performance is that what had been an especially marked drop in its support among C2 and DE supporters between 2005 and 2010 was not reversed this time around.[3] Perhaps not least of the reasons for this – and for the Conservatives' own loss of support among working class voters – is the fact that support for Ukip among C2 and DE voters was at 19 per cent and 17 per cent respectively, markedly higher than among AB (8 per cent) and C1 voters (11 per cent).

However, this is not to say that in 2015 Labour performed much as it did in 2010 in all sections of the electorate. What was distinctive about this election was that, for the most part, the older the voter, the more difficult the party found it to retain and attract their support, while the opposite was true (albeit less markedly) for the Conservatives. Ipsos MORI has estimated that Labour support was no less than 12 points higher than it was five years previously among those aged between 18 and 24, whereas it was apparently eight points lower among those aged over 65. Never before has Ipsos MORI recorded anything like as much as the 20 point difference in Labour support between older and younger voters that was in evidence in 2015. Labour may not have lost the middle-class vote, but it certainly lost the grey vote.

The competence question

However, differences between demographics themselves provide no more than possible clues as to why Labour failed to make ground – though we might note that, as ever, older voters turned up in much higher numbers than younger ones and that thus, arithmetically at least, the emergence of such a large age-divide certainly was not helpful to Labour. Otherwise, all we can say so far is that there is no immediate evidence that the party particularly lost out among the more middle-class voters that were a particular target for the party under Tony Blair's leadership, and whose support might perhaps have been thought to have been at put at particular risk by what some regarded as the rather more 'left-wing' agenda pursued by Ed Miliband.

Amid all the arguments about political direction, it should be remembered that for many voters the choice they make at the ballot box is not just about what they think of the ideological position and policies of the parties. It is also about what they think of the parties' ability to provide effective government. And it is this consideration, rather than the party's policy position, that did most to ensure that Labour lost out in 2015, particularly among older voters.

Of those who told Lord Ashcroft that they had voted according to whom they thought would be the best prime minister, no less than 67 per cent voted Conservative, while just 21 per cent backed Labour. Similarly among those who said they were voting for the team of senior party members that would provide the most competent government, 69 per cent voted Conservative and just 18 per cent Labour. By contrast, Labour was narrowly ahead, by 31 to 22 per cent, among those who made their choice on the basis of the promises made by the parties (although Ukip also performed relatively well on this criterion)(Ashcroft 2015). In short, Labour was (narrowly) ahead on policy; it was on competence that the party really suffered.

Perceptions of competence mattered, especially for older voters. As many as 40 per cent of the over-65s said that they were voting for the most competent team, compared with 26 per cent of those aged between 18 and 24. Older voters were, by contrast, less concerned than younger voters about policy promises: while 57 per cent of those in the older age group said that they were voting for the party whose promises they liked best, the equivalent figure was as high as 70 per cent among those in the youngest group (ibid).

That does not mean that Labour's policy stance was pitch-perfect – it certainly did not have the reach that the party anticipated. For older voters, cutting the deficit and the debt was relatively important and, as we might anticipate, voters who took that view were generally more likely to back the Conservatives. As many as 39 per cent of the over-65s said that cutting the deficit was one of the most important issues facing the country, compared with only 25 per cent of under-25s. The economic issue that Labour emphasised – the 'cost of living crisis' – primarily concerned younger voters. No less than 42 per cent of this group said that this was an important issue, compared with just 11 per cent of older voters (those aged 65 and over)(ibid). In so far as Labour did have a distinctive economic message, it resonated much more with younger than with older voters.

The 'economically disaffected' vote

But there is, perhaps, a bigger question to be asked about the reach of Labour's economic message. As we might have anticipated, voters' perceptions of the state of the economy were reflected in their electoral choice. However, the Conservatives did not win simply because most voters were convinced that the economy had turned around. Just 26 per cent of voters told Lord Ashcroft that they themselves were already feeling the benefits of economic recovery – rather less than the 37 per cent who said not only that they were not feeling the benefits of economic recovery, but also that they did not expect to do so in the future (ibid).

However, these perceptions were not symmetrical in terms of their apparent impact on voters' choices. Whereas the Conservatives profited heavily from the support of those who were feeling some benefit from the recovery, Labour was relatively ineffective at garnering the support of those who were not convinced that they had or would feel any benefit. No less than 64 per cent of those who said they were feeling the benefit backed the Conservatives, while just 12 per cent supported Labour. Conversely, only 12 per cent of those who did not feel and did not anticipate feeling any benefit supported the Conservatives, but just 43 per cent of this latter group backed Labour. Labour faced competition for the votes of the economically disaffected from Ukip, the Greens and, north of the border, the SNP. Rather than a failure to win over the support of relatively affluent, more 'aspirational' middle-class voters, the Achilles' heel of Labour's campaign appears to have been a failure to convince those who were sceptical about the Conservatives' economic record that Labour offered an attractive alternative.

There can be little doubt that one of Labour's key failures in the last five years was its inability to restore its reputation for economic competence. On that, all wings of the party can probably agree. But restoring that reputation need not necessarily be synonymous with embracing a conservative approach to handling the nation's finances or the economy more generally. What Labour has to ask itself is not only why it failed to attract the support of voters who were concerned about the deficit, but also why it often struggled to secure the support of those who were doubtful about the way in which the deficit and the economy were being handled in the first place. Many of the latter were working-class voters among whom Labour suffered a sharp loss of support in 2010 which they failed to reverse in 2015. Labour needs to convince the electorate not only that it can run the economy well, but that it is capable of creating a more attractive economy. Then, perhaps, voters not just in England and Wales but in Scotland too would be willing to look at the party afresh once more.

John Curtice is professor of politics at Strathclyde University and a columnist for Juncture.

This article appears in edition 22.1 of Juncture, IPPR's quarterly journal of politics and ideas, published by Wiley.

Notes

1. These figures have been calculated from wave 3 of the 2014–17 British Election Study internet panel: www.britishelectionstudy.com/data-objects/panel-study-data/^back

2. For example, Lord Ashcroft's poll (which is not weighted to reflect the actual result, and which indicated just a three-point Conservative lead) estimated Conservative support among 'AB' voters to be 40 per cent – 18 points above that among 'DE' voters. Labour support among 'AB' voters, meanwhile, was estimated at 28 per cent, 11 points below the 39 per cent among 'DE' voters. Lord Ashcroft also put support for the Conservatives at 21 points higher among those aged 65+ than among those aged 18–24, while Labour support was reckoned to be 21 points higher among the youngest group than among the oldest. See Lord Ashcroft Polls (2015) 'General Election Day Poll: CATI & Online Fieldwork: 5th–7th May 2015', 8 May 2015. ^back

3. Between 2005 and 2010, Labour support fell by two points among AB voters and four points among C1 voters, while it dropped by 11 points among C2s and by eight among DEs. See Ipsos MORI 2015. ^back

Related items

Prophet, spoiler, or free rider?: The United States and climate change

Global climate action sits firmly in the crosshairs of the Trump administration.

Resilient by design: Building secure clean energy supply chains

The UK must become more resilient to succeed in a more turbulent world.

Policy credibility and the Scottish Budget