STPs: Kill or cure?

STPs: will they kill or cure the NHS?Article

Contents

- Introduction

- The STP-finder tool

- STPs: What and why?

- ‘Secret Tory plans’

- Never knowingly underfunded?

- The case for reform

- Lifting the lid

- Conclusions: Where next?

- Annex 1: Deficits per head

- Annex 2: STPs proposing to close or significantly reconfigure hospitals or key services

- References

Introduction

To some people, they are bringing together local leaders and organisations to ‘confront…the big local choices needed to improve health and care across England over the next five years’.[1] To others, they are ‘secret Tory plans’ designed to mask damaging cuts to frontline services and privatise the NHS.

Either way, there is little doubt that the government’s latest NHS reform initiative, catchily entitled ‘sustainability and transformation plans’ (STPs), got off to a bumpy start in 2016. As we enter 2017, the big question is whether these controversial five-year plans will prove to be ‘kill or cure’ for the NHS.

In order to find out the truth, IPPR has analysed all 44 of the strategic plans now published by local NHS and local government leaders. This ‘long read’ article, alongside our new interactive ‘STP-finder’ tool, below, sets out our findings.

STP-finder tool

This tool ranks STP areas from highest to lowest deficit per head. Rollover each area for a breakdown of the scale of the financial challenge facing each STP area, and the changes that each plan is expected to bring about. The size of these deficits range between £216.15 (Durham, Darlington & Tees, Hambleton, Richmondshire & Whitby) and £768.50 (in Surrey Heartlands) per head – see annex 1 for a full ranking, including per-head and total deficits.

STPs: What and why?

The origins of STPs can be traced back to 2014, when newly appointed NHS chief executive Simon Stevens came forward with new figures suggesting that as a result of rising demand for healthcare, the NHS would face a £30 billion funding gap between 2015 and 2020.[2] He argued that if, the then prime minister, David Cameron, put in £8 billion in extra money, he would deliver £22 billion in efficiency savings across the NHS.

In what became known as the Five Year Forward View,[3] Stevens then set out how he planned to do this, with a focus on reforming frontline NHS services, including more closely joining up health and social care; moving care out of hospitals and into the community; and preventing ill-health further upstream in order to deliver ‘more for less’.

Initiatives such as the Better Care Fund[4] and the NHS Vanguards[5] soon started to test out these reform initiatives on the ground. However, such pilots only covered a small percentage of England’s health and care service. The challenge faced by Stevens was how to galvanise local NHS leaders across the country to implement these reforms at scale.

His solution – STPs – was designed to bring together local NHS and local government leaders in each of 44 areas in total, covering the whole country, to jointly set out long-term plans for health and care for their local populations. The aim was to empower local leaders to, and the make them accountable for, driving the vision set out in the Five Year Forward View in their local patch.

‘Secret Tory plans’

However, Stevens’ plans took a hit straight out the door. In the vacuum created as local leaders rushed to come together and start outlining plans for their local area – and as a result of NHS England’s misconceived decision to require local leaders to not publicly discuss or publish their draft plans – campaigning groups such as 38 Degrees launched an all-out attack on Stevens’ creation, almost rendering the whole initiative stillborn.

Branding them ‘Secret Tory Plans’[6] to privatise the NHS, 38 Degrees published estimates of the deficits faced in each STP area, and highlighted leaked plans to close or reconfigure hospitals in areas such as Leicester and the Black Country. This narrative quickly garnered support from the opposition, with Diane Abbott, then Shadow Secretary of State for Health, arguing that STPs were ‘a dagger pointed at the heart of the NHS’ and that ‘Labour… [would] resist these changes with all their powers’.[7]

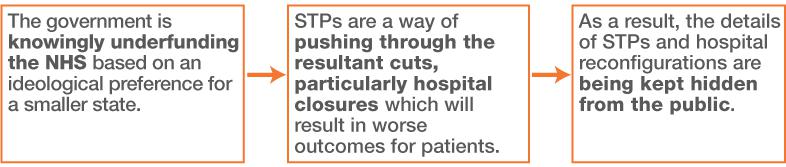

At the core of these arguments lie three propositions, set out in figure 1 below:

- that the NHS is knowingly underfunded

- that STPs are designed to push through the resulting cuts

- that the plans are being kept from the public.

The question going forward is, are these allegations true?

Figure 1

Three propositions: The ‘secret Tory plans’ take on STPs

Never knowingly underfunded?

The first claim of STP sceptics – that the government is knowingly underfunding the health and care service – is one that rings true. Indeed, IPPR,[8] as well as a large and growing number of groups and individuals from across the political spectrum,[9] have long made this same argument.

Our investigation into STPs has done nothing to change our mind. The health and funding gap figures set out in STPs across the country are truly scary, with a total funding gap across the country of £23.4 billion by 2020/21,[10] assuming that no further money is provided or efficiency savings made.

Furthermore, while our analysis finds that there is significant variation across the country (see annex 1) – with some regions such as Surrey and Greater Manchester facing a deficit (once figures have been corrected for population size) 2.5 times the size of those of other places like Derbyshire and Durham – there is not a single area in the country that is forecasting a surplus by the end of the decade.

Given the scale of these deficits and their consistency across the country, it seems highly improbable that the financial crunch in the NHS is the result of profligate frontline managers or inefficiencies alone. Rather, it indicates an inadequate funding settlement for the service as a whole.

This interpretation is backed up by historical data on NHS spending, which shows that funding will increase by an average of just 0.9 per cent per year between 2015 and 2020/21,[11] compared with a historical trend of around 4 per cent. Furthermore, international comparisons show that England spends less on health than many of its neighbours.[12]

So, why would the government stick to such a funding settlement?

At the heart of the answer lies Theresa May’s flawed belief that a lack of reform alone is responsible for the NHS’s financial problems. In a meeting last year with Simon Stevens, she reportedly said that the NHS should learn from the cuts to the Home Office, whereby the police embraced reform and maintained a steady fall in crime.[13] Her implication being, ‘Why can’t the NHS do the same?’

However, the reality is that healthcare is an entirely different service to the police.[14] Unlike crime, which has been falling over the last decade, the health service faces a growing and ageing population, which suffer from an ever-rising tide of complex chronic conditions, as well as rising medicine and treatment costs as exciting new scientific breakthroughs come on-stream. This means there is a constant upward pressure on demand and costs.

Moreover, while NHS reform may be desirable and beneficial for a variety of other reasons (see the next section for more detail), there is very little evidence that many of the reform initiatives being set out in the Five Year Forward View – such as the integration of health and care – save significant sums of money.[15]

This all suggests that Simon Stevens sold the NHS short in asking for just £8 billion back in 2014, and that Theresa May and her government are now holding him to his mistake, despite overwhelming evidence that this puts frontline services – and patients – at risk.

The case for reform

The second accusation levelled by campaigning groups – that STPs are a way of pushing through the resultant cuts, particularly hospital closures, which will in turn result in worse outcomes for patients – is less clear cut. The reality is likely to be more nuanced and less sensational than STPs’ detractors would have us believe.

Our analysis of the 44 STPs confirms that hospital reconfigurations are afoot, with some 45 per cent of the plans making clear reference to centralising or changing the services available at particular hospitals, or outright closures of one or more hospitals in their area. Furthermore, most of the other plans, while less clear, also make reference to upcoming reviews or attempts to shift care out of acute sector, which may ultimately translate into some reconfigurations.

However, while it is clear that hospital reconfigurations are happening, it does not immediately follow that these changes are motivated by efficiency savings alone, and might therefore result in worse outcomes for patients, as STP sceptics contend. There are a number of other reasons why local areas would want to pursue hospital reform (see table 1).

Table 1

Why reconfigure services?

| Reason | Explanation |

| Quality |

|

| Access |

|

| Efficiency |

|

| Prevention |

For example, there is strong evidence base that for some services, particularly A&E and specialist surgery, concentrating care in fewer locations can save lives.[16] This is partly because it allows people to access highly trained doctors and the best equipment, but also because with increased patient numbers comes increased experience and therefore fewer mistakes among staff. Likewise, some treatments need immediate access to other services such as intensive care or orthopaedic trauma, which can only be provided in larger hospitals. This has been demonstrated before, for example in London, where it has been estimated that the recent reconfiguration of stroke services has saved more than 400 lives a year.[17]

There are also instances in which treatment could be moved nearer to home (local GP surgeries, local hospitals, or in patients’ homes), both saving money and also improving access and quality of life for patients. Despite a great deal of opposition to hospital reforms, nobody actually wants to spend time in them. Only 7 per cent of people say they would prefer to die in hospital, compared with two-thirds (67 per cent) who would prefer to die at home.[18] This requires capacity and resources to be shifted out of hospitals and into the community.

This doesn’t mean that all the planned changes are justified – some may be driven by money, but many are not and therefore deserve a fair hearing. The same goes for many of the other reforms that STPs are looking to introduce. Notably, at the heart of the reform agenda is a move to integrate care within the NHS, and between health and social care within the NHS – with clear evidence that this is better for people’s health[19] and, to a lesser extent, the public purse. Most STPs are actively driving forward this agenda. They are doing so through, for example, the creation of new joined-up local services – based on success stories such as the Bromley by Bow Centre[20] – bringing together GPs, mental health services, social care, community nursing, sexual health services, diagnostics, third-sector services and even housing and employment services.

Likewise, many STPs refer to delivering on former prime minister David Cameron’s pledge to create a ‘truly seven-day health service’.[21] This is the result of evidence that shows that there are more deaths in hospitals at weekends,[22] partly due to lower staffing levels and the unavailability of certain tests and treatments. Some also outline plans to extend GP services to provide access on evenings and weekends – crucial in a world in which people work long hours and struggle to access care in the week.

A number of regions are also pursuing a greater use of new digital technologies. Numerous innovations are coming on stream, ranging from telehealth and telecare,[23] which allow people to receive support remotely over the internet, to genome sequencing, which will allow us to better understand how diseases affect different individuals and what care they should receive.[24] It is argued that the NHS is often slow on the uptake[25]; STPs offer major opportunities to speed this process up through a move towards paperless services or digital health and care.

In the rush to expose and denounce hospital closures, the potential benefits of hospital reconfigurations, as well as the case for the wider reform agenda, have gone largely unnoticed by both the media and campaigning groups. This is short-sighted and dangerous: the NHS cannot stand still as the world transforms around it. It must respond to demographic changes, new and better evidence about what works and what doesn’t, and cut-ting-edge technologies and medicines which have the potential to transform people’s health and care going forward. There is little doubt that these trends pose both risks and opportunities. However, either way, they make NHS reform both desirable and necessary, even if the service were to receive a better funding settlement. The ‘secret Tory plans’ diagnosis – that a bit more money and a return to 20th century principles and policies will revive the patient – just won’t cut it in the 21st century.

Lifting the lid

And what of the third and final claim, that these plans are a deliberate deceit by the government, with the details hidden from the public?

This argument, of course, partly hinges on the previous one: if STPs aren’t about pushing through damaging cuts designed to undermine the NHS, then the motive for keeping them secret is less clear. That said, there is little doubt that the STP process has been far from perfect, with the NHS unwittingly helping to create an environment in which the arguments made by detractors such as 38 Degrees can flourish.

For example, up until the tail end of 2016, Simon Stevens insisted that details of the STPs were kept confidential,[26] thereby creating the appearance of something untoward and enabling 38 Degrees to establish an alternative narrative about the reform agenda. However, this secrecy was not motivated by Stevens’ ‘plans to privatise the NHS’, but his determination to control the content of plans up and down the country (despite the decentralising rhetoric surrounding STPs) and the bureaucratic (rather than democratic) nature of NHS planning.

Even now, with all 44 STPs in the public domain, the 38 Degrees narrative is proving difficult to shake off, with some detractors claiming that hidden behind the health jargon and vague promises of reform lie sinister intentions. Once again, the truth is probably more banal. STPs are vague because frontline leaders have had limited time to come together and come up with reform plans in what has been a rushed process. Far from containing secret plans to privatise the NHS, some – though by no means all – STPs barely contain concrete plans at all (see below).

STPs: Variations in quality

Some good examples:

West, North and East Cumbria

- The STP provides an analysis of the issues faced by the local population and health services. It identifies a number of proposed changes in response to these issues. Some modelling has been included to show how the plan should result in improvements compared with business-as-usual.

- This STP is more developed and detailed than many others. It is likely that this can be partly attributed to prior work done as part of the Cumbria Success Regime, which has fed into the local STP process.

Birmingham

- The STP identifies a range of issues relating to health inequality, quality of care and financial deficit. It also proposes a set of 18 solutions in response.

- Each solution has its own short plan which outlines who is responsible for it, along with clear targets, timescales and an indication of the clinical and/or financial benefits it is intended to bring about.

Some room for improvement

Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin

- Although one of the longest STP documents, it lacks key details about the required changes.

- It outlines the challenges faced by the area, but often indicates general aspirations rather than a clear statement of exactly what changes are needed, how they will be made, and what improvements to the quality of care and financial situation they are intended to provide.

Surrey Heartlands

- The STP highlights that its document ‘is not a final plan, but an update on our progress and the outstanding challenges we face. It is also a further request for support, practical and financial’.

- It lacks detail and only outlines high-level objectives for planned changes to local services. An exception is Epsom Health and Care, where changes are in progress as a result of an initiative that predates the STP.

All this suggests that, while STPs are not a secret plot to privatise the NHS, there is more work to be done in communicating the contents of plans to the public – and then listening and responding to concerns. This communication effort will be vital in countering the claims of campaigning groups and other detractors, and in winning much-needed support for the ongoing NHS reform plans. Crucially, this process will require not just Simon Stevens to step up to the plate, but Jeremy Hunt and Theresa May as well (both of whom have spent more time playing the blame game than driving real change so far).

Conclusions: Where next?

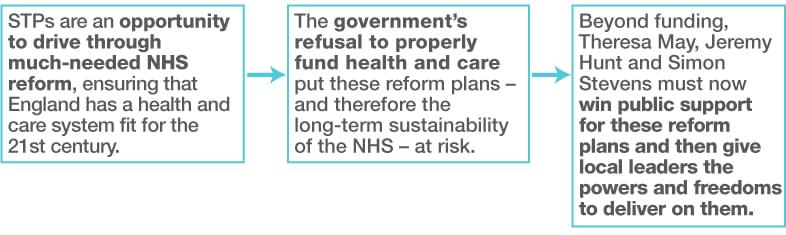

Our analysis suggests that the ‘secret Tory plan’ narrative is wide of the mark. The reality is significantly more complex and nuanced (see figure 2). Instead, STPs are well intentioned but imperfect local reform plans, with the potential to drive through the reform that is urgently needed to make our health and care system fit for the 21st century. To maximise this potential, three key challenges must be addressed going forward.

Figure 2

Three propositions: IPPR’s take on STPs

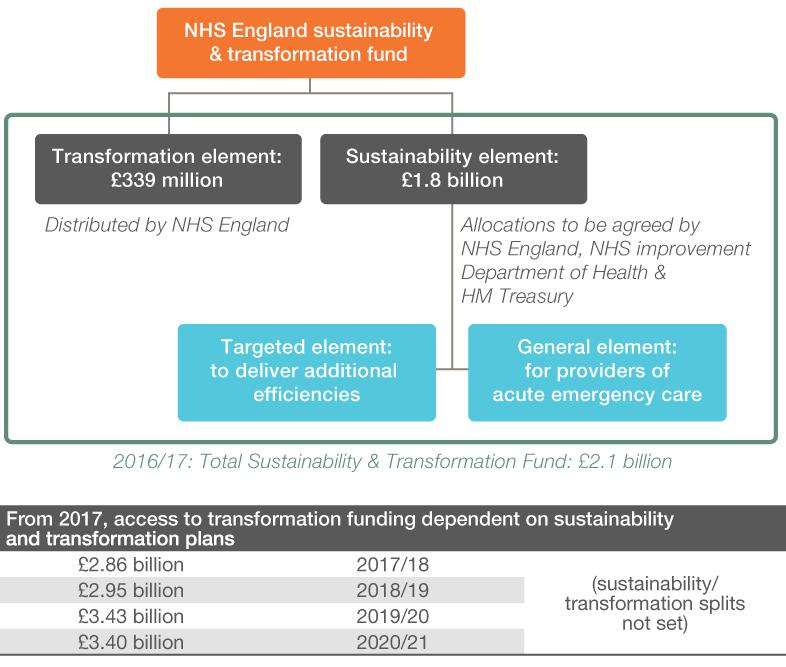

First, the government must recognise that the health and care system needs more funding. Some of this will help manage the immediate pressures of the winter crisis; however, the majority of it should be directly attached to the delivery of reforms.[27]

There is evidence that reform requires upfront investment in order to deliver.[28] This is because it requires health and care leaders to take time out of their day-to-day jobs to drive change, changes in infrastructure such as IT or buildings, and double running of services for a short time while old ways of working die out and new arrangements are put into place.

Some funding is already allocated for ‘transformation’ (making change happen) as part of the STP process, but this is dwarfed by funding for ‘sustainability’ (plugging deficits) and is likely to shrink further as the immediate pressures on the service grow over the next few years (see figure 3).

Figure 3

The Sustainability and Transformation Fund

Source: Adapted from McKenna and Dunn 2016: figure 1.[29]

In looking to rectify this problem, the government should create a new ring-fenced ‘NHS tax’ funded by a rise in national insurance. This could raise up to a further £16 billion over the next five years. This would dramatically close the funding gap which, as set out earlier, sits at over £24 billion. It would also give NHS reforms, which might close this gap further, a fighting chance of success.

Secondly, the government, in particular Theresa May and Jeremy Hunt, must support STP leaders in making the case for NHS reform, especially controversial and little understood hospital reconfigurations. So far the heavy lifting has been done by NHS leaders, with the government more eager to play the blame game than pitch in and lend a hand.[30] This will have to change if these reforms are to succeed.

Without this ‘air cover’ at the national level, it will be very hard for STP leaders to finalise their plans at the local level and start persuading patients (and, indeed, their workforce) of the merits of these changes. And the evidence is clear that without the backing of local populations and the NHS workforce, reforms don’t happen.

Finally, once central government has helped local leaders win support for their reform plans, they must give them the tools to deliver these changes and then step back and let them get on with it.

As it stands, STPs are non-statutory bodies, meaning that they have no formal role in the system and no powers to make decisions. They therefore rely entirely on reaching voluntary agreements among local hospitals, GPs and commissioners. As local leaders attempt to implement the contents of their plans it is likely that this will become an increasingly glaring flaw – especially if decisions need to be taken that improve quality and finances for the area as a whole, but see individual organisations lose out.

To address this problem, Simon Stevens and others should look to establish new and innovative ways of giving STP leaders real powers to intervene in their local area.[31] In doing so, it may well be worth other areas following Greater Manchester’s lead in pursuing something akin to a devo-health deal,[32] as this is in effect an ‘STP with teeth’ (that is, more developed governance). This will not permanently negate the need for legislative change to reverse some of the complexity created by the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, but it will at least allow local leaders to get on with much-needed reform in the mean-time.

The authors would like to thanks GSK – and in particular James O’Leary – for their generous support of this project.

Annex 1

Deficits per head

| Deficit per head | Total deficit: (‘do nothing’ scenario) | |

| Surrey Heartlands | £768.50 | £614,800,000 |

| Greater Manchester | £714.29 | £2,000,000,000 |

| North West London | £649.50 | £1,299,000,000 |

| Birmingham & Solihull | £647.27 | £712,000,000 |

| North Central London | £642.86 | £900,000,000 |

| Nottinghamshire | £628.00 | £628,000,000 |

| Cambridgeshire & Peterborough | £560.00 | £504,000,000 |

| West, North & East Cumbria | £560.00 | £168,000,000 |

| South West London | £552.00 | £828,000,000 |

| South East London | £549.41 | £934,000,000 |

| Norfolk & Waveney | £545.00 | £545,000,000 |

| The Black Country | £538.46 | £700,000,000 |

| Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly | £528.00 | £264,000,000 |

| Staffordshire | £492.73 | £542,000,000 |

| Sussex & East Surrey | £480.00 | £864,000,000 |

| Devon | £464.17 | £557,000,000 |

| Northumberland, Tyne & Wear | £457.86 | £641,000,000 |

| Herefordshire & Worcestershire | £420.00 | £336,000,000 |

| Cheshire & Merseyside | £416.25 | £999,000,000 |

| West Yorkshire | £400.28 | £1,000,700,000 |

| Leicester, Leicestershire & Rutland | £399.30 | £399,300,000 |

| Hertfordshire & West Essex | £391.43 | £548,000,000 |

| South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw | £380.67 | £571,000,000 |

| Gloucestershire | £376.67 | £226,000,000 |

| Lancashire & South Cumbria | £357.50 | £572,000,000 |

| Somerset | £350.00 | £175,000,000 |

| Bedfordshire, Luton & Milton Keynes | £345.56 | £311,000,000 |

| Bristol, North Somerset, South Gloucestershire | £339.44 | £305,500,000 |

| Mid & South Essex | £338.33 | £406,000,000 |

| Frimley | £337.14 | £236,000,000 |

| Northamptonshire | £328.57 | £230,000,000 |

| Bath, Swindon & Wiltshire | £322.22 | £290,000,000 |

| Hampshire & the Isle of Wight | £320.56 | £577,000,000 |

| North East London | £304.21 | £578,000,000 |

| Humber Coast & Vale | £300.00 | £420,000,000 |

| Coventry & Warwickshire | £296.67 | £267,000,000 |

| Dorset | £286.25 | £229,000,000 |

| Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire & Berkshire West | £281.76 | £479,000,000 |

| Shropshire, Telford & Wrekin | £281.00 | £140,500,000 |

| Suffolk & North East Essex | £275.56 | £248,000,000 |

| Kent & Medway | £270.00 | £486,000,000 |

| Lincolnshire | £260.00 | £182,000,000 |

| Derbyshire | £219.00 | £219,000,000 |

| Durham, Darlington & Tees, Hambleton, Richmondshire & Whitby | £216.15 | £281,000,000 |

Annex 2

STPs that propose to close or significantly reconfigure hospitals or key services such as A&E or maternity

- Bedfordshire, Luton & Milton Keynes (BLMK)

- Cheshire & Merseyside

- Cornwall & the Isles of Scilly

- Coventry & Warwickshire

- Devon

- Dorset

- Durham, Darlington, Teeside, Hambleton, Richmondshire & Whitby

- Herefordshire & Worcestershire

- Leicester, Leicestershire & Rutland

- Lincolnshire

- Mid & South Essex

- North West London

- Northumberland, Tyne & Wear & North Durham

- Shropshire, Telford & Wrekin

- South West London

- South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw

- Staffordshire & Stoke-on-Trent

- Suffolk & North East Essex

- The Black Country

- West Yorkshire & Harrogate

References

[1] NHS England (2016) ‘Health and care bodies reveal the map that will transform healthcare in England’, press release, 15 March 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2016/03/footprint-areas/ [<<back]

[2] NHS England (2016) NHS Five Year Forward View: Recap briefing for the Health Select Committee on technical modelling and scenarios. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/fyfv-tech-note-090516.pdf [<<back]

[3] NHS England (2014) Five Year Forward View. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf [<<back]

[4] Bennett L and Humphries R (2014) Making best use of the Better Care Fund: Spending to save?, King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/making-best-use-of-the-better-care-fund-kingsfund-jan14.pdf [<<back]

[5] Lewis R (2015) ‘New care models explained: How the NHS can successfully integrate care’, Health Service Journal, 10 March 2015. https://www.hsj.co.uk/comment/new-care-models-explained-how-the-nhs-can-successfully-integrate-care/5082594.article [<<back]

[6] Stewart H and Taylor D (2016) ‘NHS plans closures and radical cuts to combat growing deficit in health budget’, Guardian, 26 August 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/aug/26/nhs-plans-radical-cuts-to-fight-growing-deficit-in-health-budget [<<back]

[7] Abbot D (2016) 'STPs - A Dagger Pointed At The Heart Of The NHS', blog, Huffpost Politics, 14 September 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/diane-abbott/nhs-reform-stps_b_12004806.html [<<back]

[8] Pearce N (2014) ‘Let’s talk about tax (and why the NHS needs it)’, blog, IPPR, 22 April 2014. http://www.ippr.org/blog/lets-talk-about-tax-and-why-the-nhs-needs-it [<<back]

[9] Mason R (2016) ‘Hammond facing growing Tory rebellion over social care crisis’, Guardian, 29 November 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/nov/29/tory-mps-press-philip-hammond-over-nhs-and-social-care [<<back]

[10] 29 of the STPs include local authorities’ social care deficits in their figures; 15 STPs base their figures only on NHS deficits. [<<back]

[11] King's Fund (2016) ‘The NHS budget and how it has changed’, webpage. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/nhs-budget [<<back]

[12] Appleby J (2016) ‘How does NHS spending compare with health spending internationally?’, blog, King’s Fund, 20 January 2016. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2016/01/how-does-nhs-spending-compare-health-spending-internationally [<<back]

[13] Campbell D (2016) ‘No extra money for NHS, Theresa May tells health chief’, Guardian, 14 October 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/oct/14/no-extra-money-for-nhs-theresa-may-tells-health-chief [<<back]

[14] Timmins N (2016) ‘Can the NHS and social care be expected to withstand financial pressures as police and defence services have in the past?’, blog, King’s Fund, 18 November 2016. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2016/11/nhs-and-social-care-police-and-defence [<<back]

[15] Barnes S (2014) ‘Integration will not save money, HSJ commission concludes’, Health Service Journal,

19 November 2014. https://www.hsj.co.uk/sectors/acute-care/integration-will-not-save-money-hsj-commission-concludes/5076808.article [<<back]

[16] Farrington-Douglas J, with Brooks R (2007) The Future Hospital: The progressive case for change, IPPR. http://www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publication/2011/05/future_hospital_1556.pdf [<<back]

[17] Morris S, Hunter R M, Ramsay A I G, Boaden R, McKevitt C, Perry C, Pursani N, Rudd A G, Schwamm L H, Turner S J, Tyrrell P J, Wolfe C D A and Fulop N J (2014) ‘Impact of centralising acute stroke services in English metropolitan areas on mortality and length of hospital stay: difference-in-differences analysis’, British Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4757 [<<back]

[18] Public Health England (2013) What we know now 2013: New information collated by the National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications/what_we_know_now_2013 [<<back]

[19] Goodwin N and Smith J (2011) ‘The Evidence Base for Integrated Care’, slidepack, King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust. http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/evidence-base-for-integrated-care-251011.pdf [<<back]

[20] http://www.bbbc.org.uk/ [<<back]

[21] BBC News (2015) ‘David Cameron renews NHS funding pledges’, 18 May 2015. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-32772548 [<<back]

[22] Department of Health (2015) Research into ‘the weekend effect’ on patient outcomes and mortality. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-into-the-weekend-effect-on-hospital-mortality/research-into-the-weekend-effect-on-patient-outcomes-and-mortality [<<back]

[23] Hitchcock G (2012) ‘“Do nothing on telehealth and you let down your local community”: minister’, Guardian, 3 April 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/government-computing-network/2012/apr/03/telehealth-telecare-burstow-next-steps [<<back]

[24] Gretton C and Honeyman M (2016) ‘The digital revolution: eight technologies that will change health and care’, King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/eight-technologies-will-change-health-and-care [<<back]

[25] Quilter-Pinner H and Muir R (2015) Improved circulation: Unleashing innovation across the NHS, IPPR. http://www.ippr.org/publications/improved-circulation-unleashing-innovation-across-the-nhs [<<back]

[26] Vize R (2016) ‘Will the cultural chasm between NHS and local government threaten plans?’, Guardian, 5 November 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2016/nov/05/will-cultural-chasm-between-nhs-local-government-threaten-plans-stp [<<back]

[27] Vize R (2017) ‘NHS crisis: more money must be linked to reform’, Guardian, 13 January 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2017/jan/13/nhs-crisis-more-money-linked-reform [<<back]

[28] Health Foundation and King’s Fund (2015) Making change possible: a Transformation Fund for the NHS. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/making-change-possible-a-transformation-fund-for-the-nhs-kingsfund-healthfdn-jul15.pdf [<<back]

[29] McKenna H and Dunn P (2016) What the planning guidance means for the NHS: 2016/17 and beyond, King's Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/making-change-possible-a-transformation-fund-for-the-nhs-kingsfund-healthfdn-jul15.pdf [<<back]

[30] Hope C and Donnelly L (2017) 'Simon Stevens told to “calm down” NHS furore or risk his future', Telegraph, 12 January 2017. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/12/simon-stevens-told-calm-nhs-furore-risk-future/ [<<back]

[31] Alderwick H, Dunn P, McKenna H, Walsh N and Ham C (2016) Sustainability and transfor-mation plans in the NHS: How are they being developed in practice?, King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/stps-in-the-nhs [<<back]

[32] Quilter-Pinner H (2016) Devo-health: What & why?, IPPR. http://www.ippr.org/publications/devo-health [<<back]

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.