Caring for our carers: An international perspective on policy developments in the UK

Caring for our carers: An international perspective on UK policy developmentsArticle

The UK will soon have 7 million carers, representing some 12 per cent of its people, who provide the vast majority of the care needed by sick and disabled people outside hospital. In England, real-terms spending on social care has fallen by £770 million since 2010, and local authority-arranged home care is in decline: between 2011 and 2014 the number of home care clients fell by over 13 per cent.[1] Carers’ growing and unpaid contributions to our system of care and support are now worth £132 billion a year, almost double their value in 2001. That’s equal to the cost of the NHS and four times what local authorities spend on social care.[2]

An influential history of activism and reform

Many carers, far from feeling supported as they give help to loved ones in need, face a triple penalty: deterioration in their own health, financial strain, and isolation, loneliness and a feeling of being cut off from the daily life others take for granted.[3]The 2016 State of Caring report[4] details current pressures on carers; yet the latest data shows that only 334,0007 carers in England (6 per cent of all carers) receive local authority support.

In seeking to address carers’ situation, successive UK governments have, since 1999, set out their aims, commitments and policy intentions in national carers’ strategies. A new such strategy is expected from the present government by the end of 2016. Now emulated in several other countries (including Australia, Canada and New Zealand), this approach first arose in response to the campaigns and lobbying of UK carers’ organisations. Indeed, the emergence of public policy support for carers in the UK, predating the first national carers’ strategy by over 30 years, itself arose from the mobilisation of carers (albeit not yet named as such) back in the 1960s.

When Mary Webster, responding to her own experience of caring for elderly parents, sparked a remarkable surge of grassroots support in the 1960s, and in 1965 formed the National Association for the Single Woman and her Dependants, she cannot have foreseen the global importance and scale of the issue she had identified.[5] In collaboration with politicians (of all stripes), academics, and celebrities of the day, the organisation she founded sponsored research and activism and campaigned for change. It gave rise to a new language (the Collins dictionary, for instance, finds that ‘carer’ is barely used until 1980); achieved early campaigning successes (a first tax concession for carers in 1967); spawned an extraordinary upsurge of local, grassroots carers’ groups in the 1970s and 1980s; and stimulated an ‘explosion of research on carers’ in the 1980s.[6] Today, the importance of the carers’ cause is underscored by the continued existence of a vocal and respected carers’ movement, and by three near-universal trends: population ageing; women’s rising participation in the paid labour force; and the increasing provision of treatments and care in the home, rather than in institutions.

This history gave the UK a ‘head start’ internationally in identifying carers and their need for support, and in building public policy in response. It is why many in today’s international carers’ movement have looked, historically, to the UK for leadership and inspiration. Carers in the UK were the first, globally, to have access to tax concessions (1967); to a state welfare benefit offsetting foregone earnings (1976); to a social care assessment of their needs (1995); and to the right to request flexible working (2002). Yet if we take stock today of the overall picture of UK public policy on carers, and its outcomes in terms of the support carers actually receive, it is hard not to conclude that we are falling behind other nations in addressing this crucial topic.

An international perspective on UK policy

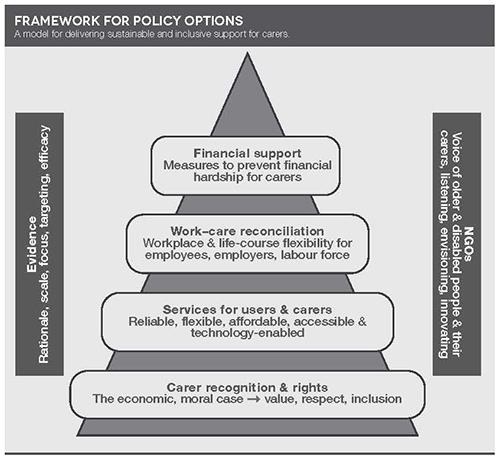

Around the world, carers can aspire to access public policy outcomes of four main types. In the UK, elements of these were achieved, incrementally, and through political pressure, campaigning and evidence-gathering, in the following order.

First came financial support in the tax and social security system. This was a response to shocking revelations in the 1960s about the financial consequences for single women of caring, and to the argument that rewarding carers with poverty was grossly unfair and required the state to act to address a social injustice.

Next came services for carers, in the form of advice, information and emotional support; sitting, respite and breaks’ services; and guidance and training on how best to manage caring. Historically, all UK carers’ organisations have predominantly used fundraising, grants and charitable income to provide such services, although some have received modest local or central government grants. Since the 1990s, most local authorities have offered some carers’ services too, often working with the voluntary sector.

Serious campaigning on workplace support for carers began in the 1980s, but it was only with the Employment Relations Act 1999 that family members gained the right to take (unpaid) time off for ‘family emergencies’. The Employment Act 2002 gave carers of a disabled child under 19 the right to request flexible working (after six months’ service), a right later extended to all employees in the Children and Families Act 2014.

The fourth policy focus involves recognition and rights for carers. Arguably the bedrock of all other support, this is expressed, albeit weakly, in the Carers (Equal Opportunities) Act 2004, and found a place in the 2008 National Carers’ Strategy. The Equality Act 2010, responding to a European Court of Justice judgment,[7] gives carers some protection from discrimination in association with the support they give to a disabled person.

Figure 1

Source: Cass et al 2014

In other jurisdictions, developments in the crucial areas of carer rights, services and workplace rights are now moving ahead of arrangements in the UK. For example, Australia’s and Canada’s Human Rights Commissions are leading the way in emphasising what a human rights approach to care and caring can bring, in starting to articulate a right to care, and in setting out the frameworks needed to make caring a real choice for carers and those cared for – the only context in which good care can be assured. Japan, Germany, France, Belgium, Sweden and other countries are now using their long-term care insurance schemes and tax systems to stimulate the development of a wider range of care, household and personal services to ensure there is good support for care at home. In the best examples, these help carers to continue to provide the care they can manage and wish to give, without turning their lives and finances upside down or suffering the health or social consequences of caring alone and unsupported.

Increasingly other nations offer, or are enhancing, statutory paid care leave arrangements, something that is still completely missing in the UK, except in forward-looking companies offering voluntary schemes. Canada recently amended its Labour Code and extended its compassionate care leave to 28 weeks; it now enables workers to share this with another family member and to claim up to 55 per cent of salary while taking leave, funding this through its employment insurance. In Denmark, employers pay full wages during care leave, a cost substantially reimbursed through local taxation. Japan has recently amended the scheme it introduced in 1999 obliging employers to offer up to 93 days of family care leave, raising compensation to users to 65 per cent of salary.

Around the world, care is under pressure, with families stressed in the face of inadequacies in public systems of support. The UK may still lead the world in articulating the challenges carers face and campaigning on this issue. But evidence from Australia, Canada, Japan and many European countries suggests the UK risks being left behind. Studies and reports have shown time and again that our care system is under-resourced, with new policy measures needed. Care legislation has been reformed, but local authorities, which must implement it, are strapped for cash and, as austerity measures have been implemented, many have lost valuable expertise.

It is time for the UK to retake the lead. If politicians value and respect carers, seeing them as the bedrock of health and social care, let’s see them vote for global excellence in local and national carer policies: enforceable rights, dependable services, a comprehensive recognition framework, and paid care leave in the suite of options from which carers who need to manage work and care can choose.

Sue Yeandle is professor of sociology and director of the Centre for International Research on Care, Labour and Equalities, University of Sheffield. She is editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Care and Caring (launching 2017).

This is an edited extract from a full-length article that appeared in edition 23.1 of Juncture, IPPR's quarterly journal of politics and ideas, published by Wiley.

[1] Age UK (2016) ‘Later Life in the UK’, factsheet. http://www.ageuk.org.uk/Documents/EN-GB/Factsheets/Later_Life_UK_factsheet.pdf?dtrk=true

[2] Buckner L and Yeandle S (2015) Valuing Carers 2015: the rising value of carers’ support. http://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/valuing-carers-2015

[3] Yeandle S and Buckner L (2007) Carers, Employment and Services: time for a new social contract? Carers UK

[4] Carers UK (2016) State of Caring 2016. https://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/state-of-caring-2016

[6] Twigg J and Atkin K (1994) Carers Perceived: policy and practice in informal care, Open University Press.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.