Cutting corporation tax is not a magic bullet for increasing investment

Article

Private sector investment in the UK has fallen to the lowest level among G7 countries – fixing it will not be easy

Later this week the chancellor is expected to deliver on Liz Truss’s campaign promise to cut corporation tax. In March 2021 Rishi Sunak announced an increase in the headline corporation tax rate in the UK from 19 per cent to 25 per cent. Kwarteng will cancel this rise, slashing tax rates for firms, and Truss floated during the leadership contest that she may even wish to cut these further, below the 15 per cent global minimum agreed last year.

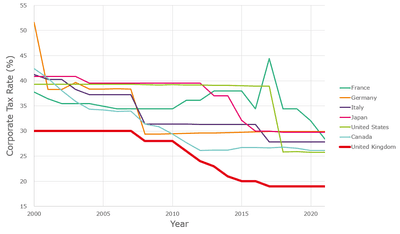

Figure 1: The UK has taken part in a global 'race to the bottom' on corporation tax

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD 2022

Sunak was right to raise corporation tax. The UK’s tax rate has been reduced consistently since 2007, from a rate of 30 per cent to today’s 19 per cent. This has been part of a broader international trend with developed countries cutting business taxes (figure 1) (Blakeley 2018). Yet in the UK, this race to the bottom has failed on its own promises (Dibb et al 2021). This blog argues that it has not delivered the increases in investment by the private sector that it was intended to achieve.

The way corporation tax cuts are justified goes something like this: the UK has low levels of productivity and low levels of capital investment, and both need to rise. By cutting tax rates, this reduces the tax bill of firms, putting money on their balance sheet that they will then invest in capital or research and development (R&D), which will result in economic growth. A secondary aim is that by having a 'competitive' tax rate (ie lower than comparable countries) the UK will be a more attractive investment destination.

The problem with this story is that it has not turned out like that. Whilst UK corporation tax rates have fallen since 2007, private sector investment is still amongst the lowest in the OECD, the lowest in the G7, and far below the average among developed economies. Corporate tax cuts have failed on their own promise.

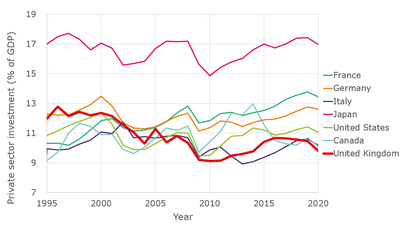

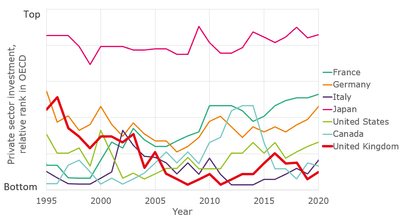

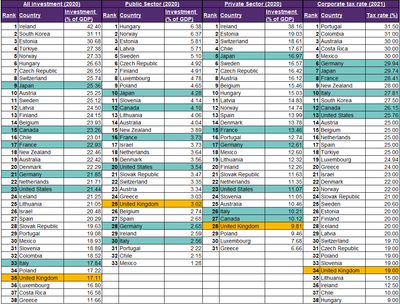

As shown in figure 2, compared to comparable countries such as the USA, Germany, France and Japan, the UK has low private sector investment as a proportion of GDP. In 2019 the UK fell behind Italy and Canada to have the lowest private sector investment in the G7 as a proportion of GDP (figure 3). Within the OECD group of developed economies, the UK fell in the rankings from mid-range in 1995 to second from bottom in 2008. In the past decade, the UK’s highest ranking for private sector investment within the OECD was in 2016, when it ranked 28th out of 35 countries. In 2020, the most recent year for which we have good data, the UK was 28th out of 31 OECD countries, and bottom of the G7 (table 1).

What is clear from this is that cutting corporation tax has failed to increase the UK’s dire levels of private sector investment. In fact, while we have been engaged in the race to the bottom on business taxation, our relative performance on business investment has been worsening.

Figure 2: Private sector investment is lower in the UK than competitors

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD 2022

Figure 3: For the past two decades the UK has consistently ranked amongst the worst performers in the OECD for business investment

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD 2022

Note: The total number of countries in the OECD grew during this period so this ranking has been normalised to account for this variation.

Table 1: The UK’s poor performance is clear when compared against other G7 and OECD countries

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD 2022

Note: The UK is highlighted in yellow and the other six G7 countries in blue.

Note: Fewer than 38 countries are shown for private and public sector investment rankings as not all OECD nations have reported their data for the year of 2020, notably South Korea which ranked highly for private sector investment in other years.

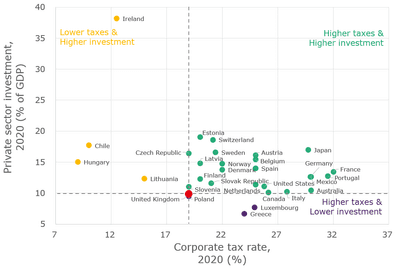

Figure 4 compares the UK to other OECD countries (for whom we have data) on levels of corporate taxation and private sector investment in 2020. Firstly, there is little to no correlation between low corporation tax and higher levels of private sector investment. Secondly, the UK is already amongst the lowest tax rates in the OECD and, as already established, the lowest levels of private sector investment. Lastly, most developed economies have both higher rates of corporation tax and higher levels of private sector investment.

Figure 4: Most developed economies in the world have a higher tax rate than the UK and still foster more private sector investment

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD 2022

There is an argument that the UK will always have a significantly lower rate or private sector capital investment than other nations because our economy is skewed towards services rather than capital-intensive industry. In the UK, about 80 per cent of GDP is attributed to the service sector, similar to other countries with much higher rates of private sector investment such as France (78 per cent) and Belgium (78 per cent). Our poor investment performance cannot be attributed to our economic make-up alone.

What can we conclude from this?

- Cutting corporation tax is no panacea for raising investment

- Over the past decade we have cut corporation tax, and this has failed on its own promise of increasing private sector investment

- Despite having some of the lowest levels of corporate taxation in the OECD, we also have some of the lowest levels of business investment

- Most of our competitors have much higher levels of both corporation tax and investment

It is worth exploring why cutting tax seems to have had such little effect in boosting investment. What does motivate businesses to invest in the UK? At its most basic, firms invest when they see future opportunities for growth and profit. Whilst cutting taxes on businesses increases the amount of revenue they can devote to investment, it does not foster future growth opportunities, and it neglects other barriers to investment.

Wider barriers to investment may include poor digital and physical infrastructure, gaps in skills provision, political and institutional instability, an unsupportive policy environment, poor access to international markets, and poorly designed or outdated regulations and standards. In addition, firms are not motivated to invest in capital, innovation or productivity improvement in an uncompetitive environment and there are some signs that competition in the UK has declined since 2008 (CMA 2022). In an economy ripe with obvious investment opportunities and few barriers to investment, tax cuts would probably provide an additional boost to investment, but the fact that this has not happened in the UK is a sign that there is a wider malaise in the economy that must be remedied. Tax cuts are not a magic bullet and are no substitute for serious, informed policymaking.

So, if the government were serious about raising investment and growing the economy, what policies would be worth pursuing?

Commit to an industrial/economic strategy

- To really increase investment government must commit to a proper, wide-ranging strategy of informed policy that seeks to increase investment and productivity by removing barriers to growth and fostering opportunities for investment. As IPPR has recommended in the past (Jacobs et al 2017) this approach should seek to improve investment both at the technological frontier but also in lower-productivity 'long-tail' sectors such as care, retail, and hospitality. Such an approach calls for sectoral expertise and better policy overall, rather than broad-brush measures.

Target a mission-oriented approach

- A mission-oriented approach to policymaking, as prominently advocated for by Mariana Mazzucato, has potential not just to direct economic activity towards societal objectives (eg net zero), but also to increase investment. When government’s actively set a direction of travel and clear missions, businesses have a better idea of future growth opportunities. Such an approach, if well-designed, can 'crowd-in' private sector investment with catalytic government investment and policy (UCL Commission for Mission-Oriented Innovation and Industrial Strategy 2019; Deledi et al 2019)

End the chop-and-change policy churn

- This week the chancellor will announce a new approach to growth and industrial policy. This will be the fifth government with a new approach in just eight years: the coalition’s ‘Eight Great Technologies’, Sajid Javid’s austerity tenure as business secretary, Greg Clark and Theresa May’s Industrial Strategy, Rishi Sunak’s Plan for Growth, and now the new Truss administration. This chop-and-change of policy and objectives is confusing for businesses and undermines UK economic credibility and stability, damaging investment (Wilkes 2022). The UK seriously needs a period of consistency in its economic policy if we are serious about growing our economy.

Adopt a whole-government approach to growth

- The UK should take inspiration from the Biden administration’s efforts and set out a 'whole-government' approach. It is not just the role of tax and the Treasury to support growth, it will require the right policies to be in place across different policy areas. This is because achieving growth will be about solving a whole range of 'drivers' as diverse as housing, energy, transport infrastructure, skills policy, and childcare.

Tax reductions should be targeted

- Where reductions in tax are judged to be necessary, they should be narrowly targeted to avoid them being overly costly, supporting unproductive (or rentier) firms, and reduce 'dead-weight' costs where public funds support expense that would have happened anyway.

These solutions are broader and more strategic than the tax cutting rhetoric that we will hear this week, but this is somewhat the point. Driving up private sector investment, productivity, and growth are hard. They are the product of all the UK’s policies in aggregate and our economic strategy (or lack thereof). The UK’s relative decline and dire performance is clear, but fixing it will not be easy. There is no magic bullet. Beware anyone who tells you there is.

George Dibb is head of the Centre for Economic Justice at IPPR.

Related items

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.

Delivering control and compassion: Reflections on the home secretary's speech on immigration reform

The last six months for the home secretary have been quite a whirlwind.