Do we face secular stagnation?

Paul Krugman on secular stagnation: ‘We have entered a world in which virtuous advice to be prudent will spell failure.’Article

The author was speaking at a panel event in Oxford organised jointly by the Sanjaya Lall Memorial Trust, Green Templeton College, and the Department of Economics at the University of Oxford. We are very grateful to them for allowing us to reproduce the transcript of the event (watch the full discussion). Particular thanks go to Rani Lall of the Sanjaya Lall Memorial Trust.

We have been in the midst of an extraordinary catastrophe for the advanced, wealthy countries of the world. If you look at any kind of projection of where we were supposed to be economically from 2006 or '07 to 2014, and compare it with the actual outcome, it has been catastrophic in terms of growth, employment and living standards. And what is really strange is that it is a catastrophe that hasn't come about because something bad has happened externally. There hasn't been a plague. Instead, there has been a malfunctioning of the economic system.

Keynes talked about having magneto (engine alternator) trouble at the beginning of the Great Depression, and once again we are having magneto trouble. What should be just a narrow technical problem has been awesome in its negative effects.

Think of the fact that my spending is your income and your spending is my income. If both of us decide that we must stop spending at the same time then we have a problem, because our incomes go down and we are frustrated in our attempt to spend less than our income. The income falls match the spending rather than the other way around. It seems like it ought to be a simple story to get across, but it isn't. As it turns out, there are several levels to this.

One is the conventional view in economics that there is something that equilibrates the system. Interest rates fall and induce people to spend more, and that is what prevents falling incomes. That might be true for mild shocks, but what if interest rates cannot fall far enough? Then we really do have a problem. We can no longer count on any simple mechanism to make sure that there is in fact enough spending in the economy.

The actual economic problem is the zero lower bound on interest rates. You cannot have interest rates below zero, except for tiny technical deviations, which is enormously important. If you take seriously the possibility of an inadequacy of demand then you find yourself in a looking-glass world in which nothing behaves the way you had expected it to. Our problem is that we have an insufficient ability to produce because of a lack of demand – not a problem of technology, raw materials or labour.

Analogies between individual households and the economy as a whole, and between households and the government, do not apply at all. We have entered a world in which virtuous advice to be prudent will spell failure. This is the classic paradox of thrift in which, as people collectively try to save more, the economy becomes depressed and businesses are much less willing to invest. An increased desire to save translates into less not more investment in the future. We are also in a world of what Gauti Eggertsson and I have been calling the 'paradox of flexibility', where if you cut wages to stimulate employment growth then you make the problem much worse, because you cut demand.

In what follows, I use US data because there are fewer distracting factors. We have been in this world of zero interest rates, when zero is not low enough, for more than five years now. We entered the liquidity trap and hit the zero lower bound on interest rates in 2008, about the time that Lehman Brothers failed. Yet it used to be said that the chance of hitting the zero lower bound is very small and surely not more than 5 per cent in any given year. But if you look at the low-inflation era, which reaches back to the mid-1980s, we have spent seven out of 30 years in this bizarre world where virtue is vice and prudence is folly. It suggests that we have a very serious problem. It gets worse if you think that there is actually a trend – that in fact it is not simply depression economics but a period of 'secular stagnation'.

Secular stagnation says that the extended period of depression that we have been going through since 2008 has become the normal state of the economy, that we have an economy that is increasingly prone to getting into situations in which the normal tools of policy do not work. What you really ought to be doing are counterintuitive things that are intellectually adventurous and flexible. Yet since policymakers are not adventurous and flexible (with very rare exceptions) you are stuck and you have very prolonged periods of depressed economies.

The doctrine of secular stagnation, a version of which has recently been revived, dates back to Keynes. It was given the name and a clear exposition by the American Alvin Hansen in 1938, who proposed that declining population growth would make secular stagnation the norm. As it turned out, that didn't happen, because there wasn't a decline in population growth – we had the baby boom after the second world war.

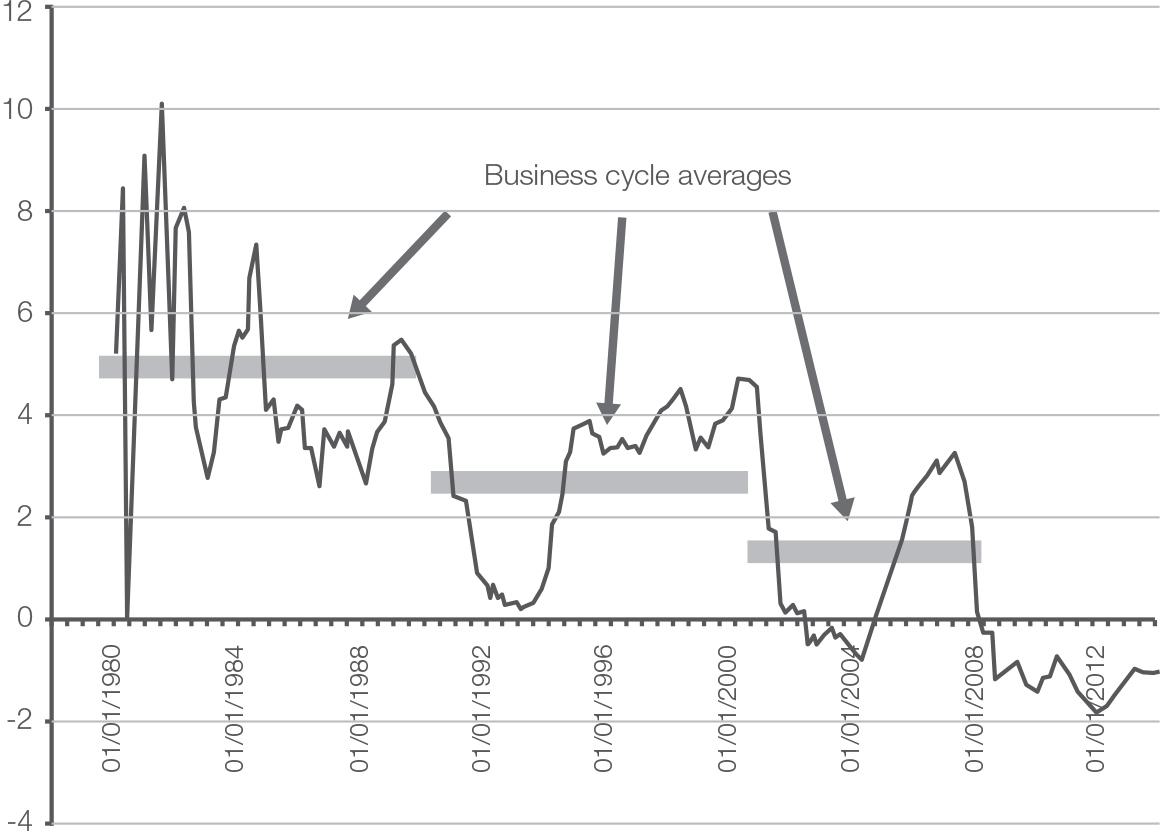

Why should we believe in secular stagnation now and what does it mean? First, there is a fair bit of evidence that we are in fact increasingly prone to episodes in which conventional monetary policy is not good enough. I will paint a simple and helpful picture (see figure 1). These are real policy interest rates – the nominal federal funds rate, which is the very short-term interest rate that the Fed effectively controls, less core inflation (the rate of change of prices excluding volatile components like food and energy).

To get an estimate of the real interest rate – of what we think should matter – you need to take an average across whole business cycles, because obviously it fluctuates a lot. There is the Reagan–Bush business cycle, the Bush–Clinton cycle and, again, the Bush cycle. By looking at these three recent business cycles, you see that each successive cycle required lower interest rates than the last in order to get out of the slump. In fact, each successive slump has been harder to get out of. The real interest rate that seems to be necessary on average for our business cycle keeps falling. Even in the 2000–07 cycle it was not easy to escape the slump – even then the Fed was flirting with something like the stagnation that we have had since the 2008 crisis. The amazing thing is that this occurred despite an extraordinary surge of debt. We have not yet reached the end of the current cycle – and it may be a very long way off – but already it looks like the real interest rate will be lower again.

Figure 1

US real interest rates and cycle averages, 1980–2013

The last two cycles previous to the current one were the two greatest debt and asset price bubbles in the history of humanity. First the 'dot-com' technology bubble, which we thought was a big deal at the time, and then the housing bubble. The drastic rise in household debt throughout these cycles is obviously unsustainable. The expansion between 2000 and 2007 was disappointing, given that it took place when households were borrowing on an unprecedented scale. We then had a moment of crisis when people said that there was too much debt and people either chose to or were forced to start paying down debts, or deleveraging.

Even if the downward trend in debt in the end turns out to be only a temporary event, we are not going to resume the upwards slope. We cannot return to borrowing at the rate we did. Over the seven-year period of expansion, households were borrowing around 4 per cent of GDP and expanding their debt. That this cannot happen again means you are taking 4 per cent off demand – even once the financial crisis is over, you still have a really major drag on the economy because what we had before was based on unsustainable growth in household debt. That is another reason to think that not only is there a downward trend, it is also going to be much harder to restore full employment than it was before. But that is not the end of the story.

Going back to Hansen, his central concern was population growth. Certainly we know Japan's shrinking working-age population was central to its two lost decades of stagnation. We are going through a similar if not yet exact demographic challenge today. For example, in the US, the baby-boom generation began in 1946 and will start to hit retirement age in 2020 – working-age population growth has slowed to a crawl.

Why does that matter? Well as the population expands it creates a demand for investment and other things, such as new housing, factories and office parks. At first approximation, we think that if interest rates and the cost of capital are the same then the capital stock will want to expand at the same rate as GDP. So if capital is about three times GDP, then GDP growth of 1 per cent will require investment to be around 3 per cent of GDP. If we knock off a percentage point from the underlying growth of the population, and so from the trend growth rate of GDP, then you are reducing demand for investment by the equivalent of approximately 3 per cent of GDP. If we think that gains from technology are slowing, that makes it even worse.

If we take a combination of the end of the great debt bubble – which is something like 4 per cent of GDP lost to demand – plus the slowing of population growth and potential growth – which is around a further 3 per cent lost – nature is giving us, in effect, an incredible austerity policy, a non-fiscal contraction functionally equivalent to 7 per cent of GDP. This makes Cameron and Osborne seem like nice guys.

As a result, we are probably looking at a situation where it is hard to avoid a persistently depressed economy. This does not constitute a crisis, but it says that the state of the world that we have been living in since 2008 may well be the new norm. That is not to say that we will never have growth, because every once in a while the economy will expand. If you look at the Great Depression there were periods of great expansion; in Japan's lost decade you can see that GDP grew in most years. But the problem is that it is never enough to pick up the slack, to bring the economy back to full employment.

Does that mean nothing can be done? Absolutely not. First of all, interest rates. While zero is the lower bound on the nominal interest rate, it is not a lower bound on the real interest rate. If the world is telling you that there are not enough investment opportunities to make the most of savings at the current real interest rate then you need to get that real interest rate lower. If you can convince people that there will be higher inflation then they won't sit on cash. At least in principle, you can maintain full employment as long as you have a sufficiently high target rate of inflation. People may object but then there is the second line of defence, which is that if you have things that you want to do through public investment (and God knows we do in many of our countries) then borrowing is very cheap.

The policies are not hard, but if you had a na??ve view that politicians simply do things that feel good for everyone, like printing money – well, it turns out that's not true at all. The really difficult thing is to get politicians to do things that are free and beneficial, because of the tremendous power of conventional thinking and of the desire to see things as they were in what used to be normal times.

This inaction is reinforced by two particular types of trap: the 'complacency trap' and the 'timidity trap'.

The complacency trap occurs when any individual year seems not so bad, at least from the politician's point of view. There is a huge literature in political science on the determinants of elections, which says that the absolute level of economic performance does not matter at all. What matters is the growth rate in the period in the run-up to the election, maybe six or nine months out. If you take that seriously then the optimal policy for a government that wants to be re-elected in a landslide is to throw the economy into a recession when it takes office so that it can have a boom in the last year before the election.

Governments can say that if there is some growth in the year running up to the election then that it is good enough. By contrast, central bankers understand that deflation is a very bad thing, and if modern economies were prone to the deflationary spiral that we saw in the early 1930s then I think we could rely on the bankers to do something. They actually dealt effectively with the acute phase of the financial crisis. But we also have very good evidence that modern economies do not experience severe deflationary spirals. There is enough rigidity of wages and other factors that even after years and years of being depressed, at most, what you get is a slow, crawling deflation. The great Japanese deflation has never been more than 1 per cent a year, and in fact appears to be exceptional. If you look at prolonged large output gaps of persistently depressed economies, almost none of them end in deflation. They always end up with slow inflation.

This means that there is no event forcing the central bank to respond and it becomes relatively easy to start making excuses for inaction. You can hear some of that from the European Central Bank now, which says that all the deflation is the result of falling prices in the debtor countries and that that is where it does the most harm. It is very easy to make excuses and not act.

Then there's the timidity trap, in which even policies that move in the right direction will fail unless they are aggressive enough. For policies to lower real interest rates through increasing inflation expectations to work, they generally have to be quite radical. Suppose that you have announced a target of 2 per cent inflation and the markets believe you, but then it turns out that your economy really needs the expectation of 4 or 5 per cent inflation to restore full employment. If you put in place policies to increase inflation, the markets might believe you for a little while and the economy will perk up, but it will not enough to end the deflation unless the old framework is dropped completely. We may very well be in a situation where only a radical rethink and then implementation of that rethink of policies will work.

The problem is that nothing drastic is happening. We have poor performance year after year, with wasted resources and blighted lives. We have a society that is not set up to handle long-term unemployment and yet we have this persistently difficult problem with enormous consequences. It is infuriating because none of this needs to be happening. The resources and skills are there, and the economic models that tell us what to do to get them back into use, but governments and central banks do not believe them.

Paul Krugman is the Sanjaya Lall visiting professor (kindly supported by the Sanjaya Lall Memorial Trust) and professor of economics and international affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.