Government should devolve new scrappage scheme to local areas

Government should devolve new scrappage scheme to local areasArticle

Today the UK government has received as final warning over repeated breaches of air pollution limits in sixteen areas. This comes after 220 doctors warned yesterday that the government that failing to take decisive action on this issue is putting children’s health at risk.

Last week The Telegraph reported that officials are in the process of 'drawing up plans' for a new diesel scrappage scheme to cut emissions of lethal and illegal gasses and at the weekend Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan also proposed how a London scheme could work.

Air pollution has been rising up the agenda as people become increasingly aware of its impact on public health, with gasses such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM) linked to conditions such as bronchitis, asthma, stroke, cancer, and heart disease.

Meanwhile, pressure on the government to act has also been exerted through the legal system with the government losing two consecutive court cases in the Supreme Court at the hands of campaigning group Client Earth.

As a result, the government has promised to deliver a new clean air strategy by April 2017. However, so far, there has been very little information about what this might include with growing fears - based largely on past experience - that plans will be watered down and inadequate.

At IPPR, the progressive policy think tank, we have been looking at this issue for some time. We have been very clear, the evidence shows that anything short of an explicit pledge to phase out diesel vehicles over the next decade will fail to address the air pollution crisis.

This, of course, creates a problem. There are currently 11.4 million diesel cars on the road, accounting for some 38 per cent of the total. Moreover, many people have, and continue to, purchase diesel cars because they were told by successive governments that they were better for the environment and more efficient.

This means that whilst added charges and bans on old diesel cars - such as those being introduced by London Mayor Sadiq Khan - are both tools that policy makers must reach for in trying to resolve the crisis, a balance of carrots and sticks will be needed to help people make the transition to cleaner and greener alternatives.

One such carrot is the scrappage scheme, which provides people with a financial incentive to be used to purchase new vehicles - or alternative forms of transport - in exchange for scrapping old diesel vehicles. The exact design of these policies can differ both in the size of the financial incentive and the uses to which this money must be put.

For example, from May 2009 people in the UK were offered £2,000 to scrap pre-August 1999 cars: £1,000 coming from government and £1,000 coming from the industry. However, this scheme was unambiguously targeted at creating demand in the economy, whilst other schemes such as the follow up ‘Plug In Car Scheme’ as well as counterparts in France and the US aimed at reducing emissions as well.

So, what could the governments new scrappage scheme look like?

It will need to be of sufficient size to tackle the problem, and not only focus on London. The aim should be to remove diesel cars from the road entirely over the next decade, starting with the oldest vehicles first.

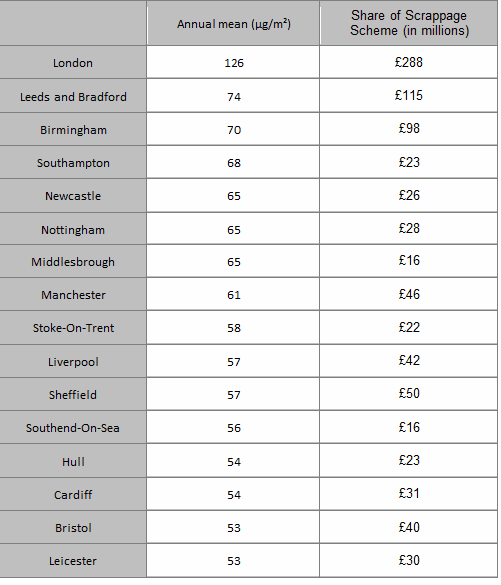

There are currently 5.6 million diesel cars on the road that were registered before 2005 (Euro 1, 2, 3 and 4). Based on population we estimate that roughly 895,000 of these are located in the top 16 pollution hot spots in the country.

Assuming a pay-out of £2,000 per car of which half is put in by the government - to match the last scrappage scheme in 2009 - this would imply that a total fund of £895 million (although it would end up costing less than this as it would be unlikely to receive 100 per cent take up). Whilst this is large it is still considerably smaller than some schemes in other countries such as Germany’s recent equivalent which totalled £4.2bn

IPPR has a had a first stab at doing this (see table below) but in the coming weeks government should do this calculation properly, perhaps also correcting local allocations for relative deprivation (e.g. an area with a comparable air pollution problem but higher deprivation would receive more of the total funding pot).

Once this allocation exercise has been undertaken, the details of the scrappage scheme should, within certain parameters (e.g. money to spend on lower emission cars, car clubs or public transport), be devolved to local areas. This would allow leaders to design financial incentives that maximise the benefit of the policy given conditions on the ground.

For example, in areas with good public transport links - places like Manchester and London - payments could be used to give free or discounted access to busses and trains only, whilst other areas might use it to work with car club providers to incentivise less vehicle ownership or link it to regional industrial policy and focus payments on the shift to electric vehicles.

Finally, it is crucial that the scrappage scheme (the carrot) is linked to reform in the regulation of roads at the local level (the stick). Areas which receive a devolved pot of the funding for scrappage should also be mandated to create ‘clean air zones’ as part of the government’s upcoming air quality strategy.

These zones - of which there are currently five - should be increased to sixteen as originally planned and must be ambitious in the reforms they look to enact. This should entail putting regulation in place to ban the oldest diesel cars, as well as upgrading public transport to be cleaner and more efficient as well.

Across Europe, leaders have read the warning signs about air pollution and acted accordingly. Germany and Norway have moved to ban not just diesel but also petrol cars, whilst Germany has invested in a network of ‘clean air zones’ which have reduced air pollution in its busiest cities. So far England has lagged behind, this must urgently change.

This blog first appeared on Huffington Post Politics and can be found here.

Harry Quilter-Pinner is a Research Fellow at IPPR, the UK’s progressive policy think tank. He co-authored Lethal and Illegal: Solving London’s Air Pollution Crisis.

Becca Antink works on public services at IPPR, the progressive policy think tank.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.