The heart health divide: Cardiovascular inequalities in Wales

Article

Our third blog on cardiovascular disease in the devolved nations turns the spotlight on Wales.

While Wales typically outperforms Scotland on key health indicators such as life expectancy and healthy life expectancy, it continues to lag behind England and Northern Ireland. One important driver of this gap is cardiovascular disease (CVD) which remains a leading cause of death in Wales.

After accounting for age, Wales recorded 12 per cent more cardiovascular deaths per 100,000 than England in 2023, and 19 per cent more deaths among those under 75. These figures point to a significant scope to reduce avoidable mortality if policymakers prioritise progress on CVD. This blog highlights stark inequalities in the prevalence, severity and risk factors for CVD in Wales, before setting out implications for policy.

The data

This analysis draws on data from the National Survey of Wales, a large-scale survey of adults aged 16 and over. We use data from 2021 to 2023, the most recent period for which microdata is available – enabling us to account for age and sex.

There are some limitations to the data. The survey covers the years of the Covid-19 pandemic, during which the methodology shifted from face-to-face to telephone interviews. This may have influenced responses, so our analysis only investigates variations in outcomes within this period. We examine inequalities in CVD prevalence and severity between the most and least deprived areas of Wales.

CVD is more common and more severe in deprived parts of Wales

Figure 1 shows clear inequalities in both the prevalence and severity of CVD in Wales (recorded in the survey as heart and circulatory conditions). The top row of the graph measures the self-assessed prevalence of heart conditions for those of all ages (left) and under 75 (right).

Overall, people living in the most deprived 20 per cent of areas in Wales are 1.15 times more likely to have heart and circulatory conditions compared to those living in the most affluent 20 per cent of areas. Inequalities are larger in the case of CVD incidence in those under the age of 75 – in this age group, those living in the most deprived areas are 1.23 times more likely to have heart and circulatory conditions than those in the least deprived areas.

Figure 1: There is a clear gradient in the prevalence and the severity of cardiovascular disease across Wales

Prevalence of heart and circulatory conditions by deprivationSource: IPPR analysis of National Survey of Wales

The gradient is steeper still when considering the severity of CVD. People living in the most deprived areas are 1.58 times more likely to say their heart condition reduces their ability to carry out day-to-day activities, than those living in the least deprived areas, rising to 1.67 times among those under 75. Thus, people in deprived communities are not only more likely to live with CVD, but more likely to be impacted by their condition in their daily life. Without tackling these inequalities, we risk them becoming even more entrenched.

CVD risk factors concentrate in deprived areas

CVD is driven by several well-established risk factors, and here too we see pronounced inequalities. This analysis focuses on four key risks.

- Obesity: Defined as having a body mass index of 30 or above.

- Alcohol risk: Measured as drinking more than 14 units per week (which the UK chief medical officers classify as ‘high risk’).

- Smoking: defined as current smoking status.

- Physical activity: measured against the guideline of at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week.

The results are shown in figure 2 below.

Figure 2: CVD risk factors are associated with deprivation, particularly smoking

Prevalence of risk factors by deprivationSource: IPPR analysis of National Survey of Wales

With one exception, all CVD risk factors show a clear social gradient in Wales. Risk factors are consistently more prevalent in more deprived areas.

The exception is alcohol: higher-risk drinking is actually more common in the most affluent communities. We estimate that 20 per cent of people in the most affluent areas drink above the recommended limits, compared with less than 15 per cent in the most deprived areas. However most evidence points to those in more deprived communities facing greater alcohol harm – a phenomenon as the ‘alcohol harm paradox’.

After adjusting for age and sex, obesity rates are around 1.47 times higher in the most deprived areas than in the least deprived. Even so, obesity remains common across Wales. Around two in ten people in the most affluent areas live with obesity, highlighting a food system that is failing everyone, while failing those in the most deprived communities most of all.

Smoking shows the sharpest inequalities. We estimate there are 3.26 times as many smokers in the most deprived areas of Wales compared with the least deprived. Physical activity also follows the pattern – with those in the least deprived areas 1.31 times more likely to reach the guidelines.

Heart health and geography

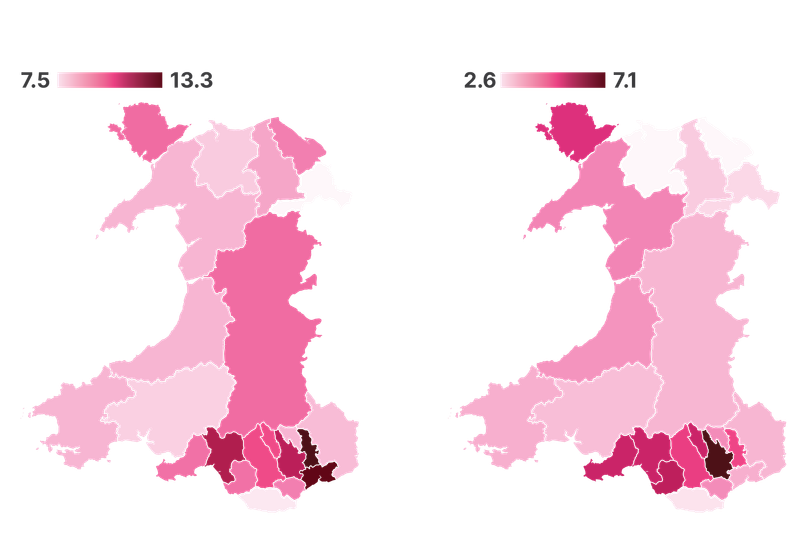

Alongside economic inequalities in the prevalence of CVD and its key risk factors, we can also observe considerable geographic inequalities in Wales. Figure 3 shows the predicted prevalence of heart and circulatory conditions for those under 75, including conditions which limit daily activities.

Across both measures, rates are highest in parts of South Wales. Torfaen records the highest overall prevalence of CVD, while Caerphilly has the highest prevalence of conditions that limit daily life. Conwy and Flintshire have the lowest rates on these measures.

Figure 3: CVD prevalence and impact in Wales

Left: Prevalence of heart and circulatory condition (under 75), right: The condition reduces their ability to carry out day-to-day activities

Source: IPPR analysis of National Survey of Wales

What does this mean for policy?

With the Welsh election fast approaching, there is a growing appetite for action on health and for reducing the burden of CVD.

The Welsh government’s commitment to becoming the world’s first ‘Marmot Nation’ – putting health equity at the heart of decision making – is an ambitious and welcome development. As our analysis shows, people living in more deprived areas in Wales experience worse health which have a negative impact on their daily lives. Without sustained action on the wider building blocks of health, persistent inequalities will remain commonplace.

However, alongside this broad ambition, Wales needs a sharper focus on reducing inequalities in the incidence and severity of CVD. Premature deaths from CVD are among the clearest and most enduring indicators of health inequality. To match its Marmot Nation commitment, the Welsh Government should set out a clear, measurable target to reduce premature CVD deaths. A defined target would focus political attention and provide a benchmark for progress.

The recent publication of the CVD prevention plan for Wales is a positive step on the road to tackling inequalities in CVD. It rightly focuses on many of the key risk factors highlighted in this analysis, including obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity and makes clear that improving population-level prevention could save lives and reduce pressure on the NHS. However, the plan currently lacks dedicated funding and clear political ownership. Its impact will depend on how it is resourced, led and delivered, particularly in communities facing the highest risk.

A crucial foundation for long-term prevention is better data. Gaps in data in Wales limit the ability of the NHS to systematically identify, manage and monitor people at high risk of CVD. Introducing an automatic data extraction programme for CVD high-risk conditions in primary care, like the CVDPREVENT system in England, would support a more consistent, data-driven approach. Without improved data, targeting interventions and tracking progress on inequalities will remain difficult.

The case for action is urgent. Avoidable deaths from CVD in Wales have remained stubbornly high for more than 25 years, and inequalities between the most and least deprived areas remain wide. If the Welsh government is serious about tackling health inequalities, reducing premature deaths from CVD through bold targets, funded prevention, improved data and effective delivery must be a central priority.

Related items

Heart of the matter: Cardiovascular inequalities in Northern Ireland

This second blog in our series on inequalities in cardiovascular disease in the devolved nations focusses on Northern Ireland.

Building a healthier, wealthier Britain: Launching the IPPR Centre for Health and Prosperity

Following the success of our Commission on Health and Prosperity, IPPR is excited to launch the Centre for Health and Prosperity.

It takes a village: Empowering families and communities to improve children's health

How can we build the healthiest generation of children ever?