How One Nation Labour can bridge the values divide

Article

Labour has every prospect of forming the next government, but only if it sets the right course. To achieve victory Labour cannot rely only on the altruists who are inclined to switch from the Liberal Democrats to Labour, important though they are for a One Nation coalition. In our electoral system, in most seats a Labour-Tory switcher is worth twice that of a Lib-Dem-Labour switcher. To win the next general election, One Nation Labour must bridge the values divide, particularly between voters whose main priority is the 'good society' and those whose main priority is the 'secure society'.

Values - a new way to think about British voters

Albert Einstein once quipped that 'common sense is the collection of prejudices acquired by age 18'. The problem is that conventional polling is not very good at measuring the type of common sense we readily observe when we meet people. It is very good at telling us what people think about certain issues but not at showing us why they think and act the way they do.

Equally problematic is that conventional accounts of the electorate tend to be dominated by class. Shortly after psephologist Peter Pulzer declared in 1967 that 'class is the basis of British party policies: all else is embellishment and detail' it became obvious that this was not so. The Conservatives started to prise Labour working-class voters from their class allegiance; at the same time Labour, and later the Liberal Democrats, began to have more success with middle-class voters.

In 1973 the British Values Survey was started by Les Higgins and Pat Dade after social psychology began to be explored as an approach to understanding major cultural shifts in society. Based on four decades of research, they identify three broad values dispositions, each comprising four sub-groups (making 12 values groups altogether). Values are more deeply held than attitudes and opinions: they are psychological dispositions we each have that reflect upbringing, background and influences.

The model poses values statements designed to develop deeper insight into the visceral nature of human beliefs. For example: 'I feel that people who meet with misfortune have brought it on themselves. I see no reason why rich people should feel obliged to help poor people.' Thirty per cent of the British population agrees with this statement, but what is fascinating is that differences between class and age cohorts are small (though men are more likely to agree with this statement than women).

However, one of the 12 values groups is four times more likely to agree with this statement than another. On almost any values statement we could produce, the differences between values groups are far greater than those across class, gender, or age.

Here is how the model works: survey respondents are placed at an exact point in a constant values space - that is, in a values map. We can then explore their propensity to agree with different values propositions. Rather than merely examine how support for individual issues breaks down by the observable characteristics of the population, we can see the world from the perspective of an individual or group.

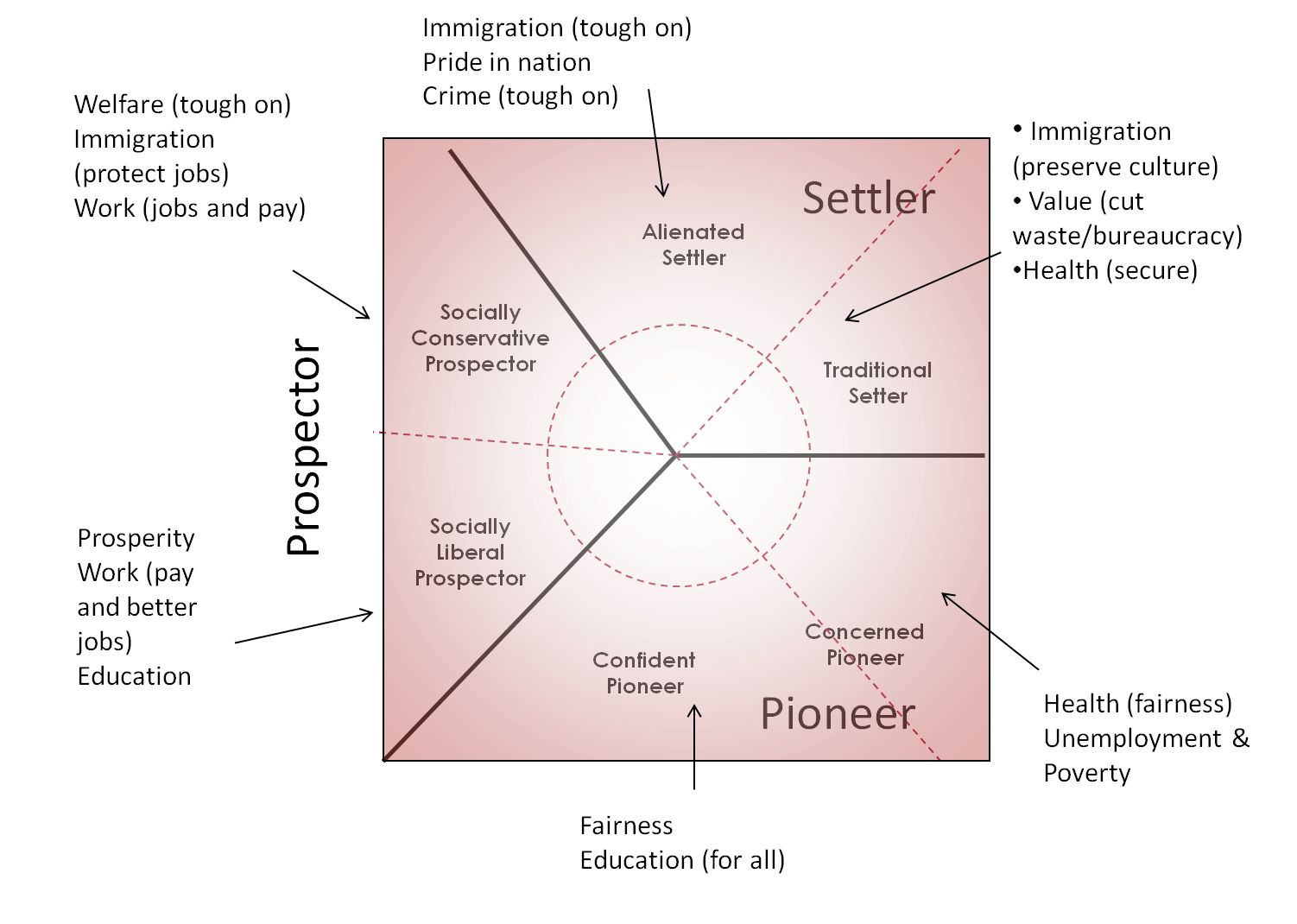

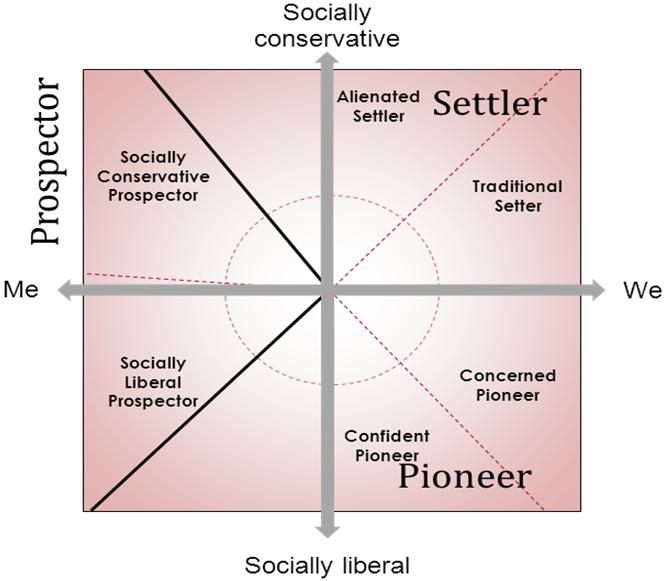

Figure 1: The values map

A simple way of understanding the values map is as follows:

- The further towards the top an individual is placed in the space, the more socially conservative they are; the further towards the bottom, the more socially liberal they are.

- The further to the left of the space an individual is placed in the space (as you look at it) the more focused on personal success they are, whereas to the right of the space individuals are more focused on community and society.

- Those inside the circle - the consensual centre - tend to have softer values than those towards the outside of the map.

The three main values groups

We can identify three main values groups based on dominant motivations and beliefs. These are called Settlers, Prospectors and Pioneers. They are useful for describing and illustrating underlying psychological shifts in the population, of the sort that are relevant to politics and, particularly, voting behaviour.

Settlers are socially conservative, generally pessimistic about the future, and believe Britain was better in the past. They are anxious about economic security in a world of finite resources, and focused on value. They want to belong and this means they are more likely to be concerned about culture and identity. Settlers want to preserve. They care about social order and adherence to clearly defined social mores. Their world is more tribal, more 'us and them'.

Prospectors can be seen as the aspirant voter. They are more focused on hierarchy, status and respect. They are optimistic about the future and can be either socially liberal or socially conservative (see figure 1). They don't do 'causes', they just want results. They are more oriented towards free-market solutions and more relaxed about differences in wealth. They are pragmatists who also like to back winners. As a result, they can be seen as the most likely to be swing voters, deciding late or changing their minds at the last moment.

Pioneers care about fairness and creating a better society. They are socially tolerant or socially liberal, and are typically positive about change and diversity. They are split between optimists (Confident Pioneers - see figure 1) and those who are anxious about the future of society (Concerned Pioneers). They are more likely to see complexity and to link the local to the global. They typically see politics as a choice between different progressive options.

In the values map below (figure 2) issues that are currently salient for each of the six outer values groups are placed in their centre of gravity. An issue becomes salient based on the confluence of events and psychological disposition.

Figure 2: Issues arranged on the values map

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the values groups

- Settlers are typically older and hail from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds, but still 19 per cent of ABs are Settlers.

- Prospectors are typically younger and are more likely to be better-off.

- Pioneers have no obvious age profile but are also more likely to be better-off.

There are gender values differences but these relate more to specific values - men are more likely to espouse power, and women benevolence - than the overall distribution of values across the map.

Perhaps most significantly, there is no clear north/south values divide (although there are regional and particularly local patterns: Scotland has more Pioneers, the North West more Prospectors, and the East Midlands more Settlers, for example).

Values trends over time

From the 2012 British Values Survey, the British population divides up as 30 per cent Settler, 32 per cent Prospector, 38 per cent Pioneer.

Two long-term trends are the growth in the number of Pioneers, which has appeared to plateau over the last decade or more, and the decline in the number of Settlers. The latter largely accounts for the decline in the importance of class as a psephelogical lens: the tribal 'us and them' world has shrunk.

However, in the last few years two major and unexpected shifts have occurred.

- Some time before 2008, for the first time in decades, the number of Settlers began to rise, before dipping again slightly. Essentially, a group in the population became more anxious about the future and let go of their dreams - they shifted from a Prospector disposition to a Settler one.

- More recently there has been a shift in values from the consensual centre towards 'louder' values represented on the outside of the values map. In 2008, half of the population mapped to the 'consensual centre'; after 2008, this fell to close to 40 per cent.

These shifts have the following implications:

- The psychology of the Settler has become - at least temporarily - more important.

- Political commentators debate whether, since the demise of Lehman Brothers, the British electorate has become more passionate about fairness, more socially conservative, or more concerned about welfare 'scroungers'. In fact, values polling shows that all these things are true.

- The shrinkage of the 'consensual centre' makes it harder for any political party to put together a coalition - to bridge the values divide.

Political support by values

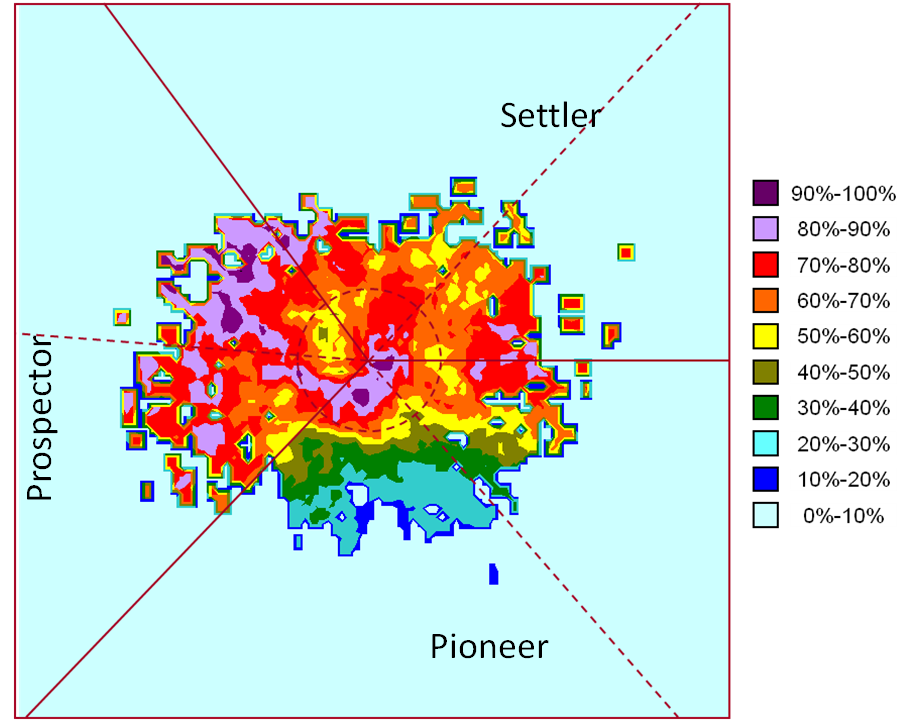

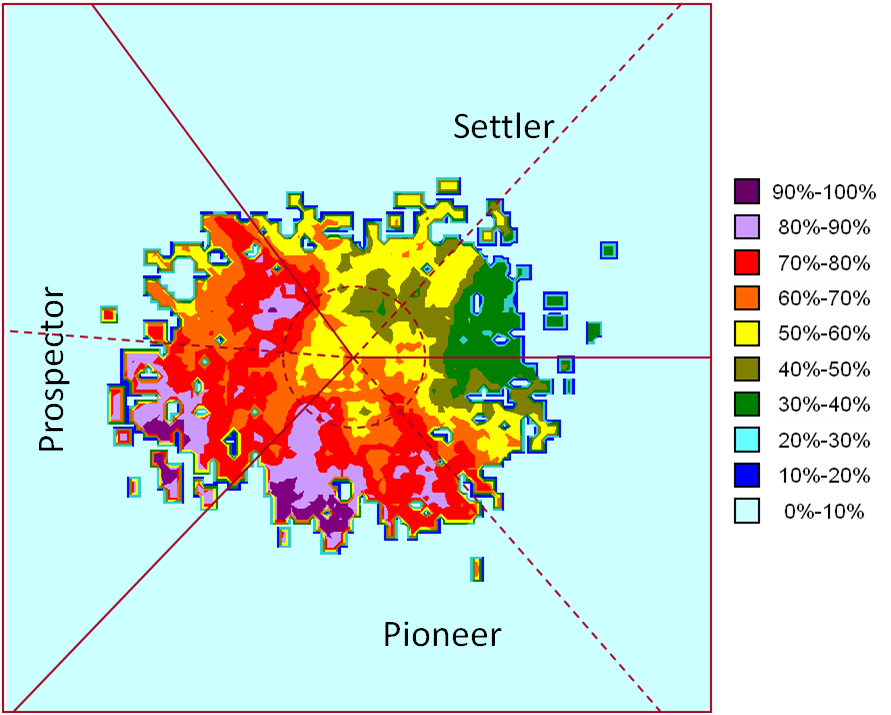

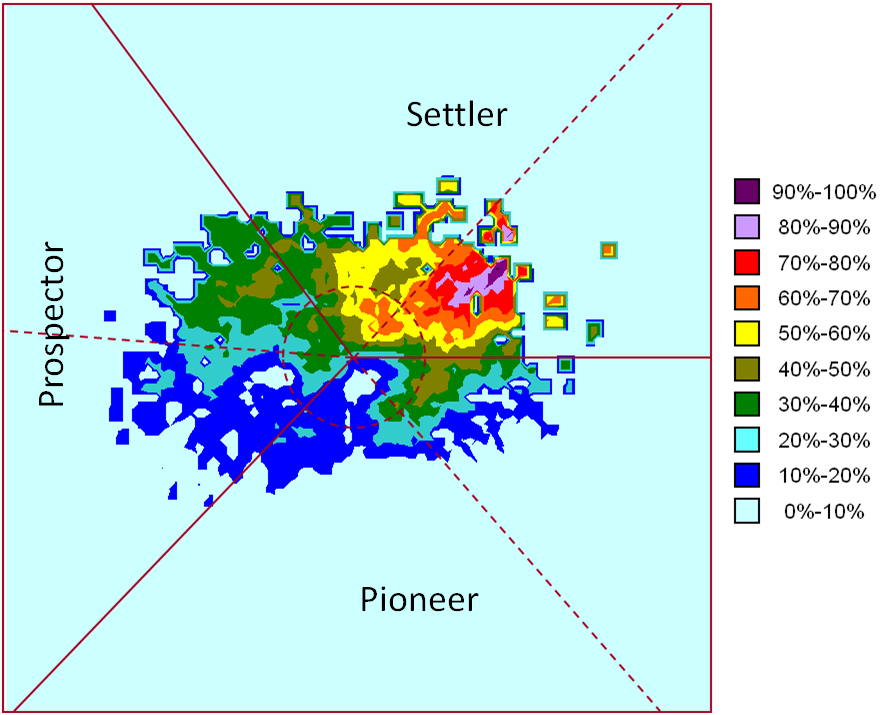

The 'heat maps' below show political support for each of the four main political parties. In each case, as per figure 1, individuals are placed in a fixed point in the map and various shades indicate degrees of support, with black being the highest level of support.

Values heat map: Conservative support

Prior to David Cameron's election as leader, the Conservatives' area of relative strength was the Settler. Cameron's modernisation project helped the Tories make progress with Pioneers right up until 2011, but in 2012 the main erosion of their support has been among 'outer' Pioneers. The Tories are doing relatively well among Prospectors.

Values heat map: Labour support

In 2000 Labour had remarkably even support across all values groups. During its time in office, Labour lost support across all values groups - including a major haemorrhage among Concerned Pioneers after the Iraq war. But overall Labour lost most support among Settlers, particularly towards the end of its time in office. The biggest single reason for this loss of support among Settlers was concern about immigration, driven by the rise in immigration levels and economic insecurity. In 2011 it looked briefly as if more Settlers were willing to give Labour the benefit of the doubt. But by 2012 the values heat map looked similar to where it had been in 2010, with renewed weakness among Settlers. Labour is doing relatively well among Prospectors and most Pioneers.

Values heat map: Ukip support

Ukip's support is heavily concentrated among Settlers, particularly Traditional Settlers. Among this group, Labour is currently in third place behind Ukip and the Tories.

Values heat map: Lib-Dem support

The Liberal Democrats have always been a 'Pioneer party'. In government they are losing support among Pioneers but hanging on to their socially liberal Prospectors.

What does this mean for Labour?

The Settler used to provide Labour's core support. There are twice as many DE as AB Settlers. So while the media narrative concentrates on the Tories' Ukip dilemma, Labour has a more profound challenge - recapturing the hearts and minds of Settlers. It used to compete for the votes of people who are now lost to Ukip, the Tories or 'none of the above'. Labour also needs to be mindful of the psychology of the Prospector. Currently all three main political parties are competitive among Prospectors. Professional mainstream parties have become attuned to the needs of this more aspirant and pragmatic voter. But Prospectors are the most likely to change their minds based on how they perceive the credibility of the economic offer political parties make to them. Which party do they believe will benefit them most? Which do they fear will make them worse off?

They tend to pay attention more in the short campaign leading up to an election. In the run-up to the 2010 general election, many Prospectors switched back to Labour amid concern they would be worse off under the Tories. In the run-up to the general election in 2015 (or before), Labour must guard against the possibility that some Prospectors will switch back to the Tories.

While they cannot take it for granted at the next election, Labour is likely to attract the support of many Pioneers who voted Liberal Democrat at the last election but then recoiled at the very idea of them going into coalition with the 'party of unfairness'.

Building voter coalitions

Today the salient issues and Labour's weakness in the values map are different than in the past, so the recipe has to be different too. Nevertheless, the principles underpinning success are the same.

Political parties do not achieve success by trying to change voters' values (they cannot push water uphill) or necessarily by building alliances on specific issues. Instead, they succeed by offering each of the main values groups enough of what they really want.

David Cameron's modernisation strategy was partially successful in building outwards to Pioneers. Tony Blair also built outwards from Labour's base, particularly towards more aspirant Prospectors. Here we can see the relevance of the contemporary debate within the Labour party: New Labour versus Blue Labour. This debate is usually articulated as a choice between two different paths, but the values prism provides a more nuanced view.

Blue Labour identifies with the Settler and reminds Labour that for many voters the 'narrative of loss' is profound. Blue Labour also recognises that the social sphere is every bit as important as the economic. For Settlers, the next election will not be so much about which party can deliver a better life but which can preserve an existing way of life.

But Blue Labour has its limitations too. While nostalgia is part of the recipe for Settlers, economic nostalgia leaves the Prospector cold. They want to move forward. For these voters, New Labour's messages about reform, investing in the future, and prosperity and jobs are essential.

Bridging the values divide

By way of initiating the debate, here are some thoughts on One Nation Labour's values bridges.

'Firm on immigration and firm on discrimination'

There is no getting away from it: Settlers are anxious about immigration. Ed Miliband has started to address the issue but have Settlers heard what he has to say? The Settler has to be reassured that Labour is not instinctively in favour of high levels of immigration. At the same time, what Pioneers really fear is not limits on immigration but that people who support such a policy are actually racist or xenophobic.

'Every household knows that to pay down debts you have to tighten your belt and earn more'

Settlers are the most likely to blame the last Labour government for the cuts. They are also very focused on value for money and anxious about profligacy. This statement rebalances Labour's message because it refers to controlling spending but it also to 'earning more'. The second part of the message can be linked to both Labour's approach to growth and to employment and wages, the latter being particularly important for Prospectors. Outer Pioneers are the only voters discussing trade-offs between growth and spending. To make the message complete for Settlers, Labour should also define a new localism based around IPPR's notion of the relational state.

'Fair on taxes and tough on cheats' and 'we want a nation where the more you put in the more you get out'

Pioneers and Settlers agree on the need for a fairer tax system. Prospectors do also when it clearly means a tax cut for them or a materially better-off version of themselves. However, socially conservative Prospectors and Settlers think the problem is that cheats get away with it, and here they are not so much referring to tax avoiders as benefit cheats. Labour has already advocated that the contributory principle be restored to the welfare system and this provides a strong potential values bridge between Pioneers and socially conservative Prospectors and Settlers.

Conclusion

Einstein also pronounced that 'it is harder to crack prejudice than an atom'. This may be true, but it is no longer harder to measure it. The values prism offers profound insight into the core beliefs of the electorate and what drives voter behaviour.

In order to win next time around Labour must blend Blue with New. It must work particularly hard at earning the trust of the Settler, though it cannot do this by jumping with both feet into 'Settler territory'. To do so would result in a catastrophic loss of trust. Instead it must build bridges from Pioneers to Settlers and socially conservative Prospectors. Settlers and Pioneers share certain core beliefs about fairness, but Settlers have to be reassured on social change before their bond with Labour can be rekindled.

One Nation Labour has put in place many of the building blocks for success, but it must now take the next step. This is not so much a need for detailed policy but rather a need to fill the gap between broad themes and detailed policy with clear statements of intent which bridge the values divide.

This is an edited version of the full-length article which appears in issue 20(1) of Juncture, IPPR's journal for rethinking the centre-left.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.