The uphill battle ahead for 'responsible capitalism'

Article

Nobody would dispute the observation that the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis has had a profound effect on Britain's economy. Four years on, the country has yet to return to the level of economic activity it enjoyed immediately before the crisis hit. The biggest challenge facing Britain's politicians is how best to restore economic growth while getting the country's ballooning government deficit back under control.

It is therefore little wonder that Ed Miliband, the leader of the opposition, is seeking to convince us that, if returned to power in 2015, his Labour party would adopt a different economic strategy from the one it followed while in government between 1997 and 2010. His vision, as outlined initially in last year's party conference speech and in more detail in the previous issue of Juncture, is one of 'responsible capitalism'.

According to Miliband, the financial crisis has 'led people to question the post-1970s consensus about the extent to which unfettered markets always result in optimal outcomes'. Instead, he argues, there is a recognition that there needs to be a 'more active role for government in making the market economy work' both through increasing incentives on business to take a longer view and through adopting a more interventionist industrial policy. By 'making the market economy work', however, Miliband does not mean simply making it more productive but also fairer. 'Responsible capitalism,' he writes, 'is the right agenda for Britain today because it offers the prospect of forging a fairer economy that works for the majority.'

But is there any evidence that in the wake of recession people in Britain have acquired a renewed faith in government as a key actor in the search for a more effective economy and a fairer society? In short, is social democracy alive and kicking in the British electorate once more?

Published earlier this month, the latest report from the British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey provides unique insight into the long-term trends in the ideological mood of the British public. Conducted annually since 1983, the survey enables us to compare how the public has reacted to recession this time around with the way it responded to previous, albeit largely less serious, economic reversals in the early 1980s and '90s. If there really is a new consensus, we ought to have witnessed a change of public mood that is sharper and more profound than anything we witnessed on those previous occasions.

In line with Miliband's argument, there is certainly some evidence of increased public recognition of the need for the government to do more to help industry. Every year, BSA presents its respondents with a list of areas of government activity and asks them to nominate their first and second priorities for more spending. Figure 1 shows the proportion each year who said that 'help for industry' was one of their top two priorities.

Figure 1

Given that the list of possible priorities includes health and education, we perhaps should not be surprised that it has never been the case that large proportions have chosen 'help for industry' as one of their top two. Nevertheless, attitudes have varied over time. In particular, whereas in the early, booming years of this century only around one in 20 named help for industry as a priority, in the last three years between one in 10 and one in eight have done so. The recession has clearly left some mark on the public mood.

However, so far this mark is etched no more deeply than it was during the recession of the early 1990s. On that occasion as well, respondents' support for more help for industry doubled from around 6 per cent to 12 per cent, only to fall away again once the economy turned the corner. Meanwhile, the issue is evidently still a much lower priority for the public now than it was when the economy was just beginning to emerge from the recession of the 1980s. On this evidence, then, there is little sign of a new, more profound questioning of the relatively hands-off relationship between government and industry that has prevailed for much of the last quarter century.

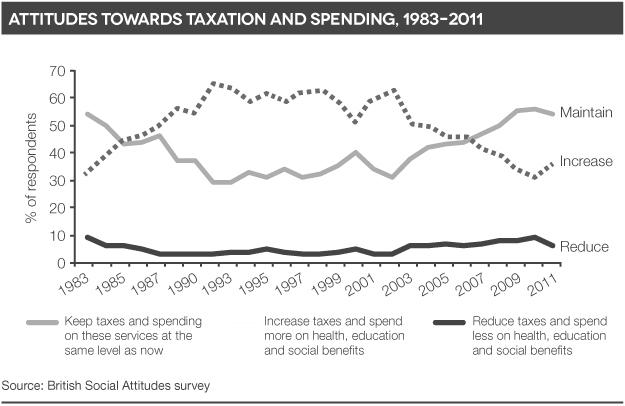

With recession has come the prospect - and now the initial reality - of cuts in public expenditure. We might wonder whether this experience is serving to remind people of the value of government activity. As figure 2 shows, during the course of the last decade support for more public spending has in fact been in continuous decline, in reaction to the substantial increase in public spending that the New Labour government, contrary to its initial instincts, eventually instigated. It appears that as spending increased it gradually satisfied the public appetite for better public services. Indeed, at 31 per cent the level of support for more spending in 2010 was not only just half of what it was in 2002 (63 per cent) but also the lowest since 1983.

Figure 2

Now, however, according to the latest survey, support has begun to edge up, by five points to 36 per cent. But, while of some interest, such a modest reversal hardly constitutes evidence of a long-term shift towards a demand for more active government. At most it suggests the current administration will, like its predecessors, find that this is an area where it is very difficult to satisfy public opinion for very long, because attitudes always tend to move counter-cyclically against the direction of current government policy. In any event, Miliband himself has indicated that responsible capitalism needs to be 'fiscally neutral', given the prospect of limited resources for years to come.

Evidently, we need to look at deeper measures of public opinion if we are to have much prospect of identifying a more profound shift in attitudes.

One such measure, included on each year's BSA survey, is provided by the combined responses to a number of statements that are designed to tap the degree to which people value equality and are willing to endorse government action in its pursuit. Respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with each of the following five statements, all of which suggest that at present Britain is too unfair and unequal a country.

- 'Government should redistribute income from the better off to those who are less well off.'

- 'Big business benefits owners at the expense of workers.'

- 'Ordinary people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth.'

- 'There is one law for the rich and one for the poor.'

- 'Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance.'

As one might expect, someone who agrees that 'big business benefits owners at the expense of workers' is also quite likely to agree, for example, that 'there is one law for the rich and one for the poor'. The same is true of the other statements. This means we can sensibly bring the answers to these five propositions together to get an overall indication of how pro- or anti-equality - or how 'left-wing' or 'right-wing' - an individual is. If, as Miliband believes, there is renewed interest in a fairer economy, fuelled perhaps by the rows about bankers' bonuses and executive pay, then we should find that overall more people than before agree with a majority of these statements and thus can be regarded as being on the left of British politics.

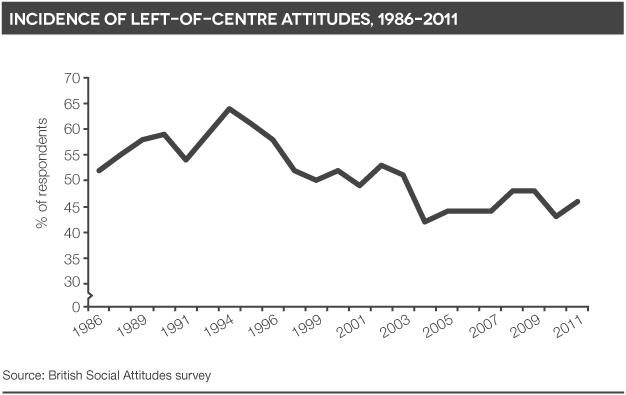

Figure 3, which shows the proportion of people who are 'left of centre' on the BSA scale,1 uncovers a rather disturbing picture for Ed Miliband. Britain is seemingly less concerned now about equality and fairness than it was during the last recession of the early '90s. In the period between Tony Blair becoming Labour leader in 1994 and his resignation as prime minister in 2007, the proportion that proved to be 'left of centre' on the BSA scale fell by 20 percentage points, from 64 per cent to 44 per cent. While more recently this drift has shown no sign of continuing any further, there has so far not been any consistent evidence of a marked reversal either. Despite those rows about bankers' bonuses and excessive boardroom pay, the most recent reading is - at 46 per cent - little different from that obtained in 2007.

Figure 3

Far from rejecting a post-1970s consensus, it appears the British public continue to adhere to a relatively inegalitarian mood of more recent origin, one that emerged in the wake of New Labour's acceptance of the premier role of the market economy. If Miliband now wishes to take his party in a somewhat different direction then he is going to have to shake off that legacy. He cannot assume the experience of recession has done that job for him - at least not yet anyway.

This conclusion is underlined when we look at attitudes towards one of the specific ways in which the government can most immediately ameliorate the financial consequences of the unemployment that recession typically brings in its wake - through the provision of unemployment benefits. In office, New Labour sought to reduce what it regarded as wasteful expenditure on paying people to do nothing and instead preferred to invest resources in encouraging and facilitating their return to employment. That shift too seems to have generated a new consensus that the latest recession has so far failed to dislodge.

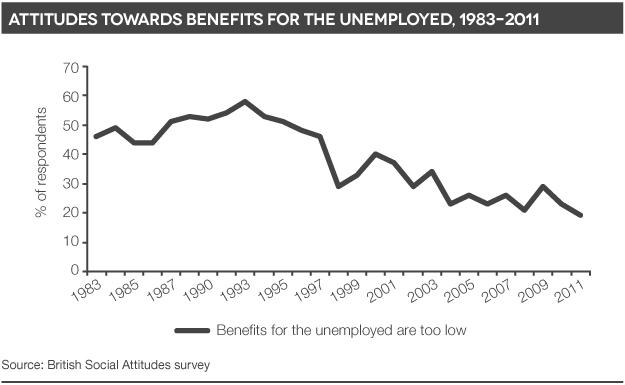

Evidence of this can be found in figure 4, which shows for the period since 1983 how many people have said that benefits for the unemployed are 'too low' when posed the following question: 'Opinions differ about the level of benefits for unemployed people. Which of these two statements comes closest to your own view: benefits for unemployed people are too low and cause hardship, or, benefits for unemployed people are too high and discourage them from finding jobs?'

Figure 4

Previously, the answers to this question showed some sensitivity to the current level of unemployment. For example, when unemployment reached its peak in 1993, the proportion saying that benefits for the unemployed were too low also peaked at 58 per cent. But shortly after New Labour came to power, equipped with a less traditional stance towards welfare, there was a sea change in attitudes: during Labour's first 12 months in office, the proportion saying that the unemployment benefit was too low fell from 46 per cent to 29 per cent. While thereafter it recovered somewhat in the short term, by 2004 it was back down to as little as 23 per cent.

Meanwhile, there is no sign that this tougher mood has been disturbed by the recession. On the contrary, according to the latest BSA survey, the proportion believing that the unemployment benefit is too low has fallen further to just 19 per cent.

One explanation might be that the level of unemployment experienced during this recession is much lower than during the downturns of either the 1980s or the '90s, and thus it has not generated similar levels of empathy with those who find themselves out of employment. Even so, such an observation simply serves to underline the point that the financial crisis alone has not been sufficient to generate renewed enthusiasm for more active government intent on ameliorating some of the inequalities in our society.

Of course it would be a mistake to conclude from this BSA evidence that 'responsible capitalism' is doomed to failure as an electoral project. Elections are more often than not won and lost on the basis of which party is thought to be best able to deliver, rather than on the basis of whose message best fits the ideological mood of the public. On that front, Labour badly needs to restore its battered reputation for economic competence; insofar as it can be developed into a narrative that persuades people that Labour has a sense of economic direction and knows how to get there, 'responsible capitalism' might help in that endeavour. But in framing its appeal for the next election Labour needs to appreciate that the recession alone has not created an electorate that has lost faith in the existing consensus. Ironically, the legacy left by 'New Labour' has, so far as public attitudes are concerned, proved to be far more durable than that.

Note

1. This scale, formed by adding together the responses to the original five items detailed in the text, ranges from 1 (most left-wing; the respondent strongly agreed with all five items) to 5 (most right-wing; the respondent strongly disagreed with all five items). 'Left of centre' is defined as a score of 2.5 or less. back^

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.