Time for Labour to establish economic credibility

Article

The temptation is obvious - allow the Coalition to dig itself ever deeper into the economic black hole into which its austerity regime has apparently plunged the nation, and then reap the inevitable reward when the public cast its verdict in two years' time. After all, does not the fate of governments depend on the performance of the economy under their stewardship? And with the kind of record that the current government has so far - no growth and diminishing living standards - is there not already little or no prospect of voters allowing Cameron and his cronies another five years in power?

So far in this parliament, Labour has often given the impression that this is an accurate representation of its state of mind. The shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, has happily and understandably seized every opportunity to say, 'I told you so,' as growth has remained elusive and the deficit stubbornly refused to diminish. But as to how his party would set about the task of restoring fiscal stability and economic health, Mr Balls has proved much more reticent. Labour has appeared reluctant to move much beyond the now outdated strategy for reducing the government deficit that was outlined three years ago by Alistair Darling in his dying days as Chancellor. But is such reticence necessarily wise?

The party is certainly right to presume that the economy matters to voters. But it does not necessarily do so in the simple straightforward manner that is often assumed - good economy, government re-elected; bad economy, government ejected. After all, if that were the case then, for example, the Conservatives would never have crashed to defeat in 1997 when the economy had already embarked on the boom that was only eventually to end in the bust of the 2008 banking crisis. Rather, as the Oxford political scientist, Ray Duch, and his American collaborator, Randy Stevenson, have pointed out: the really crucial question that voters look to address when deciding how to mark their ballot is, 'Which party looks best able to run the economy in the next five years?'

True, the recent performance of the economy is one of the crucial pieces of information that voters use in answering that question. But in considering that performance, voters are inclined to focus on sharp changes in the economy, which are easily identifiable with the government in power rather than on steady economic performance that might have happened whatever government was in power. Thus the relatively strong performance of the British economy after Black Wednesday was not sufficient to reverse the damage to the Conservatives' reputation for economic competence caused by the shock of suddenly being forced to exit the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (especially perhaps, given the 1992-97 government's other subsequent travails and divisions, not least over Europe).

So far, the current Coalition has avoided serious economic drama - though the announcement that the UK has lost its triple-A credit rating could perhaps now become a clear signal of a flawed financial strategy. Nevertheless, voters have already come to have their doubts about the government's ability to handle the economy effectively. Confidence began to drain away when the economy started to stutter towards the end of 2010. According to YouGov, the proportion who thought the Coalition was handling the economy well slipped from an average reading of 44 per cent in September 2010 to 36 per cent by February the following year. Currently the equivalent figure stands at just 33 per cent while no less than 59 per cent think that the Coalition is handling the economy badly.

However, the picture has not been one of ever-declining ratings. Confidence was even lower in the immediate wake of last year's budget, when a series of U-turns (that contributed to a wider impression of 'omnishambles') coincided with the revelation that Britain was suffering a double-dip recession, thereby arguably providing voters with a particularly clear signal as to the Coalition's economic incompetence. In August last year the proportion who reckoned the Coalition was handling things well had fallen to just 25 per cent. The government has managed to recover quite a lot of ground since then.

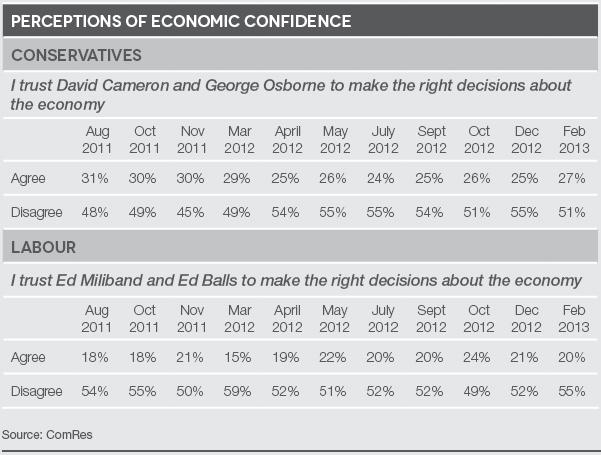

Not that voters have necessarily put last year's experience entirely out of their minds. As recently as this February, ComRes found that only 27 per cent agreed with the proposition that David Cameron and George Osborne could be trusted to make the right decisions about the economy - a proposition that comes closer to capturing voters' feelings about prospective competence than YouGov's question on how the economy is being handled at present - while no less than 51 per cent disagreed. As figure 1 shows, this finding is typical of those that ComRes have recorded ever since last spring.

Yet for all the Coalition's apparent economic mistakes and travails, when asked that vital question, 'Who do you reckon could do a better job in future?' more voters are still inclined to nominate the existing regime rather than the Labour opposition. For example, in December, ICM found that 35 per cent reckoned that David Cameron and George Osborne were 'better able to manage the economy properly' while only 24 per cent chose Ed Miliband and Ed Balls. In the same month, YouGov reported that 37 per cent trusted Cameron and Osborne to run the economy while only 26 per cent placed their confidence in Miliband and Balls.

Figure 1: Perceptions of economic confidence

True, the gap in perceived economic competence appears to be somewhat narrower now than it was a year ago; in January 2012, ICM put Cameron and Osborne ahead by 46 per cent to 28 per cent. But that is because fewer people retain confidence in the Coalition's abilities; there has been little sign of any restoration of confidence in Labour's abilities. As the figure shows, still only 20 per cent agree that they 'trust Ed Miliband and Ed Balls to make the right decisions about the economy', much the same proportion as were of that view as much as 18 months ago. So far as most voters are concerned, Labour are just as unconvincing as the Coalition when it comes to their ability to run the economy.

This picture is very different indeed from the one that prevailed before Labour came to power in 1997. According to the Gallup polls of that era, Black Wednesday alone proved sufficient to catapult the party into a clear lead over the Conservatives when voters were asked which party could handle the country's economic difficulties best. Labour then proved able to consolidate that lead when Tony Blair became leader. There was no doubt then about where voters thought economic competence lay.

One reason for the difference is clear - in contrast to the position in the run up to 1997, Labour still has the millstone of its own recent performance in government hanging around its neck. The damage was evident while Labour was still in power. Doubts about the party's economic competence were growing even before the financial crisis approached meltdown and Gordon Brown struggled to demonstrate leadership. But as the financial storm grew, so Labour's reputation was hit hard and, as a result, during the course of 2008 the Conservatives emerged with a clear lead on economic competence for the first time since Black Wednesday.

That damage still has to be repaired. For all the doubts the public have about the Coalition's austerity programme - little more than a third think it is good for the economy, while nearly half believe it is inflicting damage - the need for such cuts in the first place is still widely being blamed on Labour. In the polls it has conducted so far this year, YouGov have found that, while on average 27 per cent blame the Coalition for the current spending cuts, as many as 36 per cent blame Labour. Another 26 per cent reckon that both share the responsibility. In short, approaching two-thirds of the electorate still point the finger of blame, at least in part, at Labour for the continuing problems in the nation's finances.

Doubtless, in time this perception will eventually erode. Repeated Coalition assertions that responsibility for the mess in the nation's finances lies wholly at Labour's door will surely eventually begin to wear thin. Maybe, but not necessarily at a rate that will ensure the argument has lost its resonance by 2015. The 36 per cent who mostly blame Labour now is only marginally lower than the 38 per cent who were doing so at the beginning of 2012, or the 40 per cent who did so at the beginning of 2011. At that rate, Labour would have to be out of power for three terms before it was no longer being blamed for the cuts.

So Labour would be unwise solely to rely on an ailing economy as its pathway to power. As well as taking every opportunity to attack the Coalition's record, it needs to convince voters that it has the ideas and ability to avoid both the mistakes of the Coalition and the errors of its own still-not-so-distant past. The task will not necessarily be an easy one; before Black Wednesday the economy was historically an issue on which the party struggled to develop a clear lead. Nevertheless, achieving such a lead again is likely to prove vital; not since 1964 has the party managed to win an election without managing to be at least on a par with the Tories on perceived economic competence. In particular, the last time voters went to the polls after a Tory-run economy had been in recession - in 1992 - Labour remained behind the Tories on economic competence and the voters duly opted to keep the Tories in power.

In fairness, Labour has begun to paint a picture of what 'One Nation Labour', unveiled by Ed Miliband last autumn, might mean in terms of a strategic approach to running the economy that is different from both that of the current government and that of the Blair and Brown era. Economic growth, we are told, is to be achieved from the 'middle out' - that is, by putting more spending power in the hands of those in employment through such measures as the promotion of the living wage, enhancing the skills and thus the earning power of non-graduates, and tax cuts that benefit the less well paid.

Potentially this is a big idea, an argument that greater economic equality would be beneficial for us all. It is now even graced by an emblematic tax policy that distances the party from both Brown and Cameron - the introduction of a mansion tax to fund the restoration of a 10p income tax rate. But much of what we are promised remains remarkably vague. How will the 'stranglehold' of the big six energy companies be broken? How will the 'price rip-offs' of the train companies be stopped? How will businesses be enabled to 'develop deeper connections with each other'? Most voters may not follow the detailed answers, but in their absence they may well form the impression that Labour's talk is better than its walk. What better time to start giving them some of the answers than after a Budget in which Mr Osborne will doubtless once again be struggling to convince voters that he still does have the answers to Britain's economic problems?

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.