More than half a million employers at risk of bankruptcy without further support

Article

As the Covid-19 vaccine is rolled-out across the UK, there is hope that the acute health crisis might soon come to an end. Yet, the crisis afflicting businesses is far from over. We find that almost one third of UK firms (weighted by turnover) are at risk of collapse in the spring if support is not extended. This corresponds to almost 600,000 employers at risk, together employing approximately 9 million people.

This is the risk if business support schemes end abruptly in March and April, as is currently planned, when many otherwise viable businesses will likely still be relying on them. This could lead to a sharp increase in business failures, dealing a lasting blow to the economic recovery.

The full economic consequences of the pandemic have so far been hidden

Existing support schemes, such as government loan guarantees and the furlough scheme have been successful in helping businesses and prevented widespread bankruptcies. Yet, in March and April much of this support is due to end. Applications for loans close in March, no further grants have been announced and the furlough scheme is to close at the end of April. Together, these will cast huge uncertainty over many firms balance sheets.

Moreover, with corporate indebtedness surging and current business closures potentially extending into May, loans can only support firms so far. The focus on loans is over-burdening companies with debt, harming their ability to invest and grow, and hampering a future recovery. Furthermore, it is insufficient to prevent the closure of otherwise viable firms. The government have introduced a ‘Pay as you Grow’ scheme, extending bounce-back loan repayments, yet this doesn’t address the bigger issue of overall worrying levels of indebtedness across the private sector nor the early withdrawal of vital support schemes.

In Taking a Stake we highlighted that Covid-19 restrictions and lockdowns have contributed to an estimated cashflow deficit of £180bn (up to Dec 2020). Businesses’ savings, or cash reserves, were only sufficient to cover half of this gap (Bank of England, 2020) putting firms at risk of collapse. Recent figures confirm the severity of the issue.

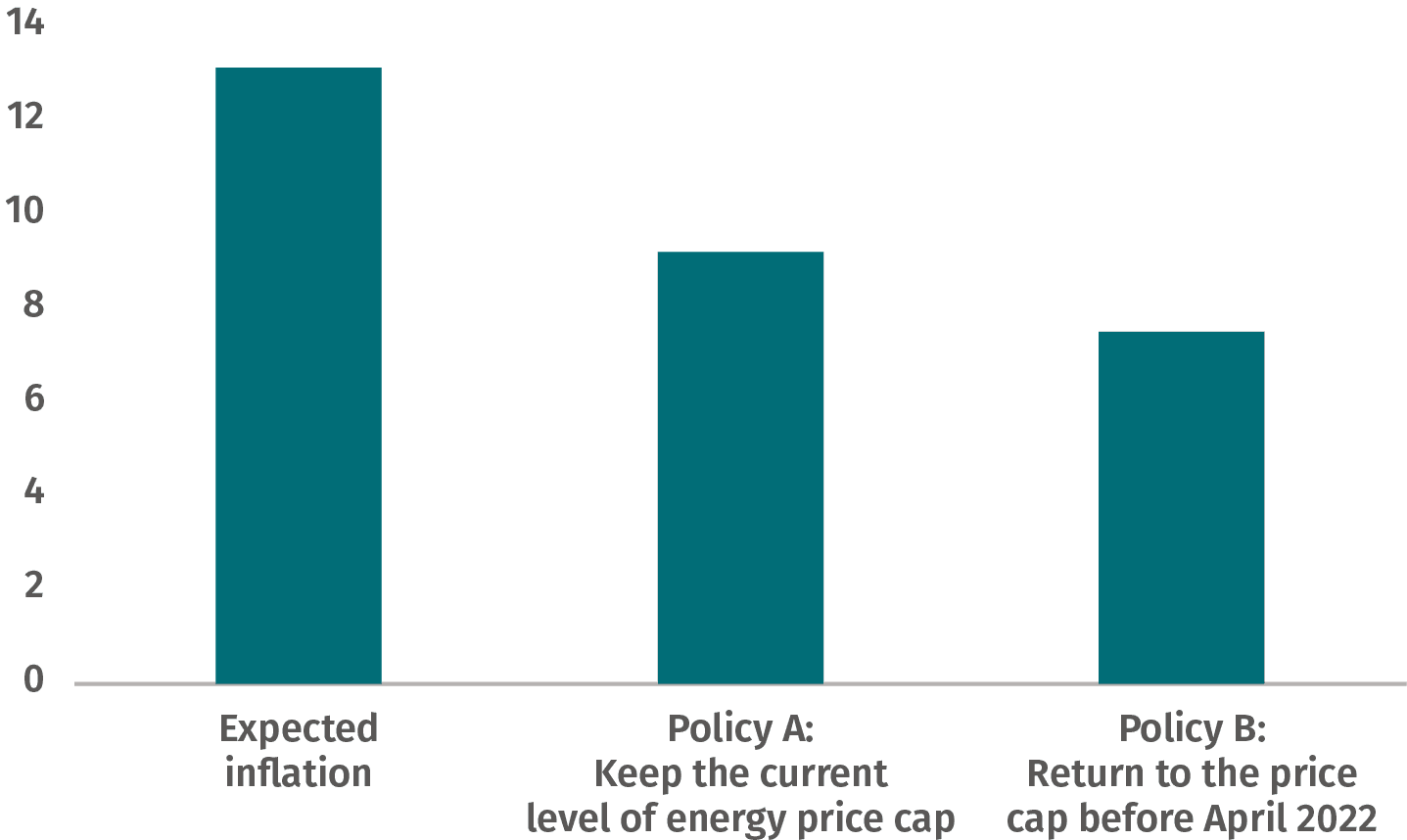

FIGURE 1 : Recent grant support schemes did not improve the cash buffers of firms

% of firms (weighted by turnover) with less than three months cash reserves

Source: IPPR analysis of ONS BICS

Taking into account the variation of cash reserves between firms of different sizes, we estimate that this corresponds to about 600,000 employers that are at risk, employing about 9 million people (see annex).

These economy-wide figures hide an even more worrying picture in some industries. When looked at on a sector-by-sector basis, we can see firms in sectors particularly affected by lockdowns (eg food and entertainment) show large increases in the number of struggling firms (figure 2). In the sector of ‘Accommodation and food service activities’ more than half of businesses now have low cash reserves. Beyond hospitality and retail – eg in construction and ‘other services’ – the number of struggling businesses has risen.

FIGURE 2 : The number of firms with low cash buffers has sharply increased since the autumn

% of firms (weighted by turnover) with less than 3 months cash buffer

Source: IPPR analysis of ONS BICS

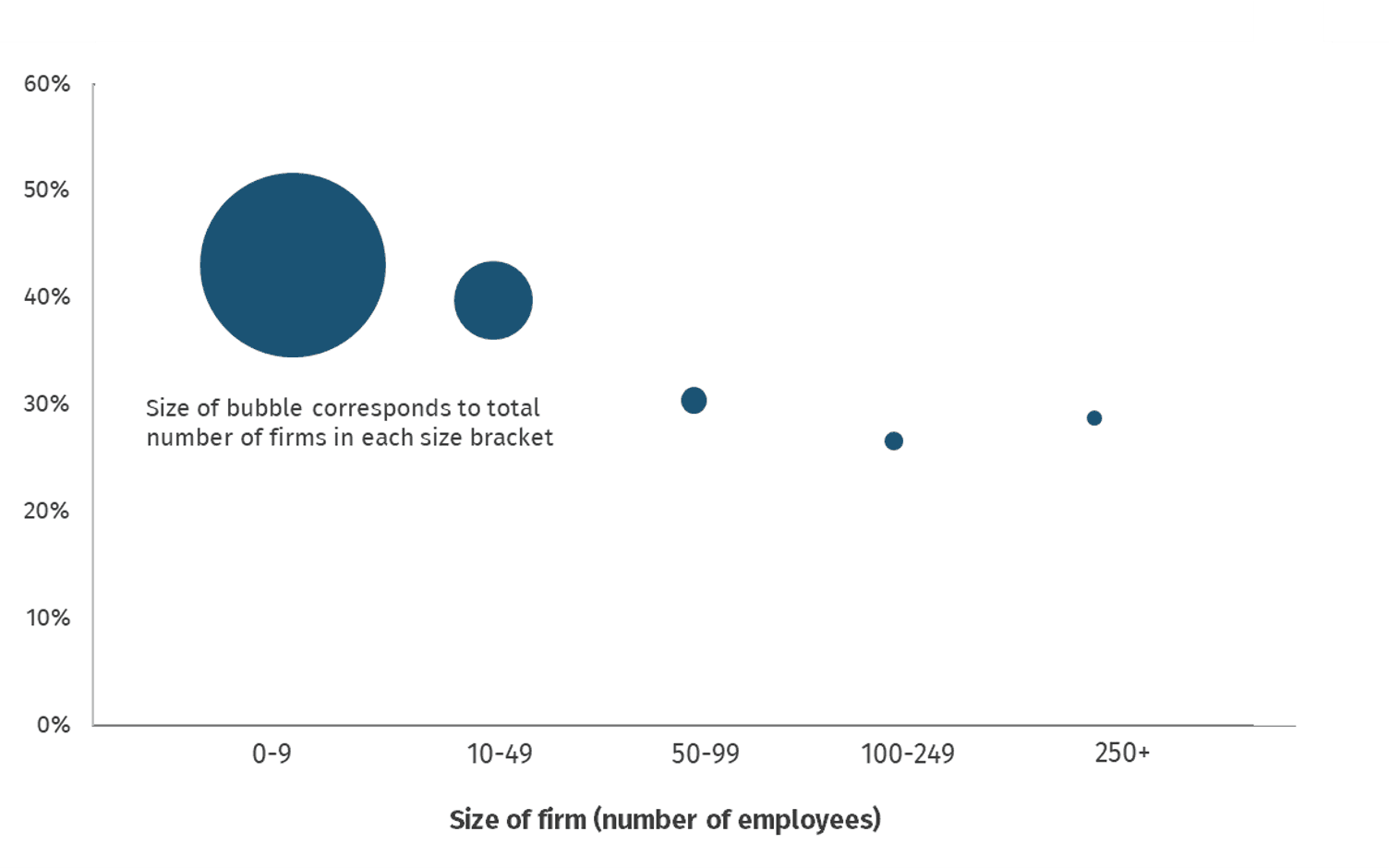

Small businesses (which jointly are responsible for a large share of UK employment) are most at risk of bankruptcy. About 40 per cent of firms with fewer than 50 employees have less than three months of remaining cash reserves.

Proposals: how to help avoid a spring of bankruptcies

Without a further extension of support we can expect see a catastrophic wave of business collapses later this year. There is no benefit to waiting until the last minute to remedy this, as many businesses need months prior notice to plan ahead. By announcing further measures as soon as possible, government can help increase confidence in a strong recovery.

1. The chancellor should remove cliff edges for existing support schemes

With the earliest possible end to this lockdown coming at the beginning of March, but full reopening expected to come potentially months later, the following cliff edges should be removed by either extending the schemes at the same level or tapering their support:

Loan guarantee schemes planned to end 31st March 2021 with loan repayments for many firms due to begin in April/May 2021 (dependent upon scheme and date of receipt of loan)

Furlough support planned to end 30th April 2021

Business rates holiday planned to end March 2021

Reduced VAT rate for the hospitality sector planned to end 31st March 2021

Repayment of deferred VAT due to begin 22nd March 2021 and repaid in its entirety by 22nd March 2022

The phase out of all these schemes should not come as a cliff edge, but rather they should be gradually reduced in a predictable way and in line with the state of reopening of the economy. For instance, the furlough scheme could be replaced with IPPR’s proposed coronavirus work sharing scheme, supporting worker retention over the next months. At the same time, the government should consider ways of targeting loan guarantees to firms most in need and with regard to a measure of business viability.

2. Grant support must be extended in proportion to business needs and lockdown restrictions

As we show above, even recent levels of grant support were insufficient to improve firms’ aggregate cash buffers. This will leave them ill-prepared for the reopening phase. The level of grant support should be better targeted, ideally calculated in proportion to firms’ needs, rather than a lump sum as is currently the case. This could follow examples elsewhere; for instance, in Germany support was allocated in proportion to previous revenues.

Further, eligibility around which types of firms qualify for grant support should be extended. The latest grants were accessible to any firm that had to close by law. Yet giving a grant to a restaurant but not its supplier, or to a car showroom but not a car manufacturer, leaves many businesses affected by restrictions without much needed support. Eligibility criteria for grants should be extended to support businesses “up-stream” in the supply chain.

3. Equity stakes are needed to complement other forms of support

As we recommended in our report Taking a Stake, in addition to loans and grants, equity injections are needed to stabilise firms’ balance sheets. With the market likely to underprovide equity support for businesses to a sufficient degree, the state should offer equity to viable firms, taking a stake in the UK’s economic recovery. This could, for instance, take place via debt-to-equity swaps for outstanding loans. In the case of SMEs, we have suggested a new equity like investment product. Related suggestions on this include recommendations from the Centre for Economic Performance and the City UK.

The government has already offered equity investments in specific cases through the British Business Bank Future Fund, as well as the targeted bail-out of Celsa Steel. We proposed that the government establish a similar scheme accessible to businesses that pass a number of qualifying conditions (such as manageable existing debt levels or prior restructuring). The fact that some recipients of Future Fund investments have immediately converted their loans to public equity demonstrates the unmet demand for this form of investment support.

Such a widespread deployment of public equity would not be without governance challenges. Yet we argue that these can be overcome through institutional innovation. In the longer term, we propose that the government could retain shares of strategically important firms, utilising these stakes through active management to support decarbonisation, for example, or alignment with wider government priorities. A Citizens’ Wealth Fund, operated as an arms-length government body, could be established to take ultimate ownership of these stakes and ensure that taxpayers benefit from the recovery in return for rescue resources committed now.

Authors

Dr George Dibb, head of the IPPR Centre for Economic Justice

Carsten Jung, IPPR senior economist

Annex: Methodology note

Cash flow buffer numbers in this blog come from the ONS ‘Business insights and impact on the UK economy’ survey released on the 28th January 2021 and previous waves. We define firms as at risk if they report having less than three months cash reserves.

We calculate the (unweighted) numbers of firms at risk by combining the (turnover-weighted) BICS cash buffer figures (by business size) with numbers from the BEIS Business Population Survey (2020). We assume that within a firm size bracket (by employment) the average turnover by firm is constant. If that is the case then the number of firms affected by size bracket is simply given by:

We calculate the (unweighted) numbers of firms at risk by combining the (turnover-weighted) BICS cash buffer figures (by business size) with numbers from the BEIS Business Population Survey (2020). We assume that within a firm size bracket (by employment) the average turnover by firm is constant. If that is the case then the number of firms affected by size bracket is simply given by: ni, at risk=wi∙ni, where wiis the ONS (turnover-weighted) estimate cash buffer shares in size bracket i and ni is the number of firms in that bracket.

Intuitively, the unweighted number of firms at risk is higher than the weighted one, because a relatively larger number of small firms are at risk that also have lower turnover. Figure A illustrates this.

The BEIS business population survey (Oct 2020) states that there are almost 6 million registered businesses in the UK private sector, of these 4.6 million do not have employees and only about 250,000 have 10 or more employees. When calculating the total population of companies at risk of collapse, our analysis focuses only on firms with employees, ie not capturing the large number of registered firms in the UK with no employees.

FIGURE A: Small firms tend to have smaller cash buffers, but employ a large number of workers

% of employers, with less than 3 months cash buffer

Source: ONS BICS and BEIS Business Population Survey

Related items

On the ground: how Scotland’s public servants experience public service reform

The failure to embed the Christie Commission's recommendations has proved to be a huge mistake

Reclaiming Britain - a response

The IPPR report Reclaiming Britain, authored by Parth Patel and Nick Garland, marks an important development in the world of progressive think tanks.

Student loan reform: Weighing the trade-offs

Millions of graduates are paying more for longer as frozen thresholds and high interest rates bite, leaving ministers with tough choices on how to deliver meaningful, targeted relief.