The Chancellor’s energy plan is a sticking plaster full of holes

Article

Today the energy regulator Ofgem has revealed the biggest ever rise in energy bills. The change will see the average cost of a household gas and electricity bill rise by £693 to £1,971 with energy costs jumping by 54 per cent overnight, potentially pushing inflation to as high as 7 per cent this year.

Left unchecked, such a rise would see those households in fuel stress (those spending more than 10 per cent of their household budget on energy) triple to around 6 million households. Energy bills for those on the lowest incomes could rise 7.5 times faster than those on highest incomes and single parents will see their bills rise 56 per cent faster than the national average.

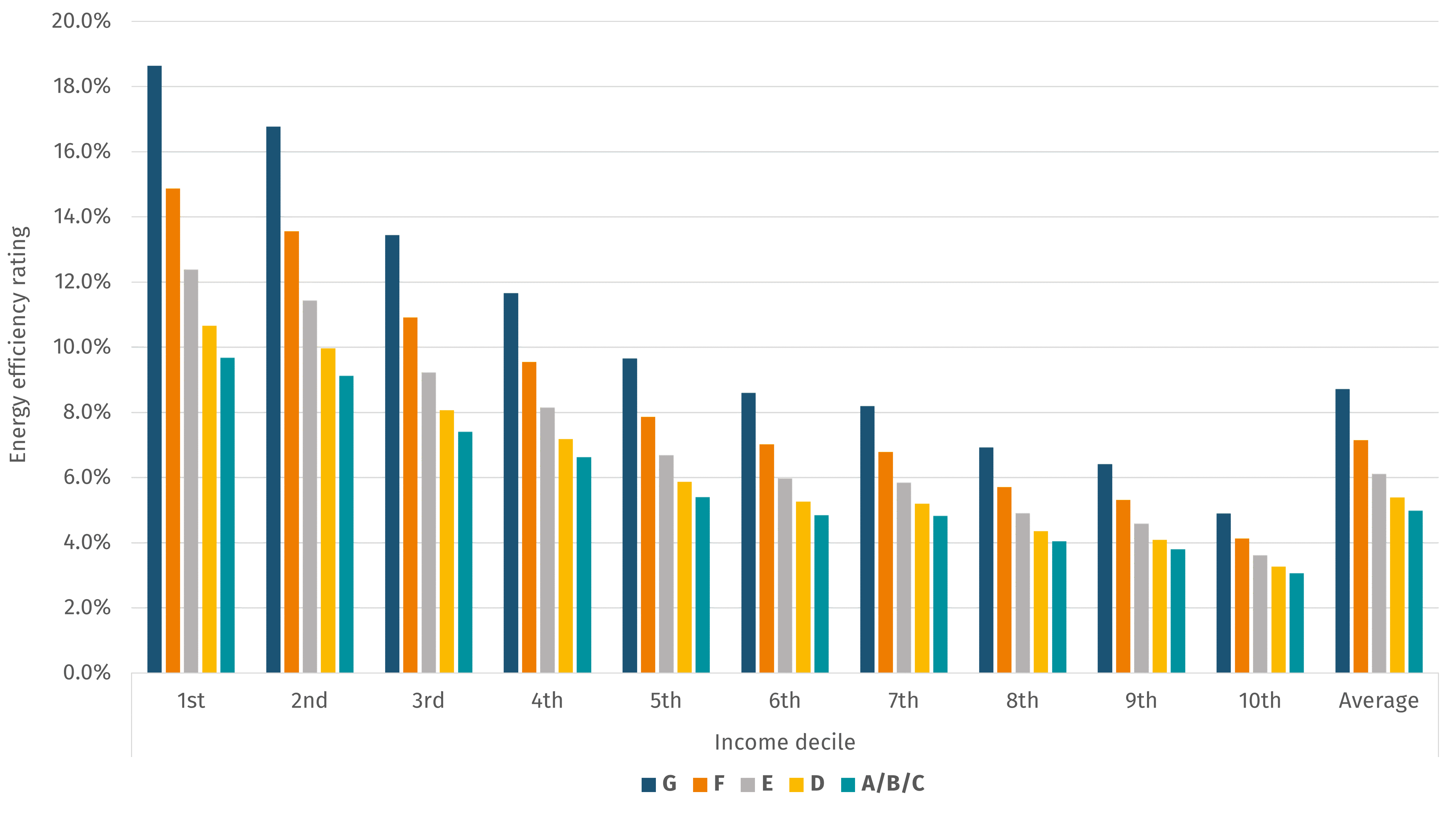

IPPR analysis shows that, in the absence of intervention, those on the lowest incomes living in the least energy efficient properties face spending over a fifth of their income on energy bills.

Figure 1. In the absence of intervention, the lowest income households living in the least efficient homes face spending well over 10 per cent of their household expenditure on energy bills and, in the worst cases, over 20 per cent of household expenditure.

Average estimated proportion of household expenditure spent on energy bills in England for a typical default dual fuel tariff by energy efficiency rating after price cap increase.

Source: IPPR analysis of ONS 2021ONS 2022

Notes: Cost increase based on raising the average household standard variable dual fuel tariff to the new price cap limit of £693. This cost increase is then applied across different income deciles’ expenditure on fuels (according to ONS 2021) and adjusted according to the differing costs associated with different energy efficiency ratings (ONS 2022). Expenditure is based on FY2019/20. In the lowest income decile, income is assumed to be equal to expenditure.

The government’s proposals

The government therefore had to intervene today. The only question was – what would it do? As IPPR and others have argued, in the short term, the threat to household finances necessitated both a broad intervention to support all households, but also a targeted intervention to support those on lower incomes who are going to be hardest hit.

Loans to energy companies

The government’s scheme to provide loans to energy companies amounts to a ‘use energy now, pay later approach’ which will see households paying back the higher bills in the long term.

But while it may provide some short-term cushioning, it will still mean households will have to pay back these costs over the medium term at a time when the cost of living is rising across the board. Moreover, it relies on the assumption that energy bills will fall in the near time, despite many analysts expecting bills to rise again in October (they could rise to nearly double the current cost to £2,400 a year) and potentially again in 2023.

There was a role for the government to use low-cost loans to spread the cost of supplier failure - failures since August 2021 will see around £94 added to energy bills from 2022 – but this should have been in addition to a more broad-based intervention such as moving legacy green levies into general taxation (see below).

Council tax rebates

The plan to provide lower income households rebates through the council tax system - a system that relies on property values that were decided when the Chancellor was just joining secondary school at 11 years old - is also very poorly targeted. IPPR analysis shows that 2 million income poor people will miss out on the automatic payments (though they will have access to discretionary funds held by councils), while 44 per cent of those with the highest household incomes – the top 10 per cent - would gain from the rebate.

Of greater concern, is that the total help being provided by the government is simply not adequate to support those on the lowest incomes who face a catastrophic hit to their incomes. IPPR analysis shows that even if every household were to get the maximum £350 possible under the government’s scheme, the vast majority of the poorest households in the bottom 10 per cent will still be in fuel stress spending more than a tenth of their income on fuel. In the very worst cases, the poorest households could be spending as much as 19 per cent of their incomes on fuel - a potentially catastrophic hit to their living standards (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Even with government loans to energy suppliers, the lowest income, lowest efficiency households could still see energy bills rise up to 18.6 per cent of annual household expenditure.

Average estimated proportion of household expenditure spent on energy bills in England for a typical default dual fuel tariff by energy efficiency rating after price cap increase and after factoring in government support, applied as a £350 rebate equally distributed across households.

Source: IPPR analysis of ONS 2021ONS 2022HM Treasury 2022

Cost increases based on raising the average household standard variable dual fuel tariff to the new price cap limit of £693. This cost increase is then applied across different income deciles’ expenditure on fuels (according to ONS 2021) and adjusted according to the differing costs associated with different energy efficiency ratings (ONS 2022). Expenditure is based on FY2019/20. Government proposals are included after calculating price cap increases as a blanket £350 reduction across all deciles (£200 from an energy bill rebate and £150 from a Council Tax rebate). In the lowest income decile, income is assumed to be equal to expenditure.

Greater action is needed in the short-term

Even with the measures announced today, likely future increases in energy bills will mean that future interventions by government will still be required. IPPR proposes:

1. Support and smooth the impact on households in the short-term

Reform environmental and social levies. While these levies represent a small and steady part of household bills and are not a driver of the current crisis, there is a strong equity argument for shifting these costs on to general taxation. Such a shift would see lower bills for around 70 per cent of homes compared to the current levy on energy bills.

To ensure this doesn’t result in much needed levies being cut in annual government spending decisions (such a risk was mooted recently by Treasury sources), this shift should be restricted to so called “legacy obligations” which are part of legally binding contracts and therefore would be extremely difficult to cut altogether. Cutting all levies would reduce the average energy bill by £180 and cost the taxpayer around £4.8 billion, while moving the legacy costs alone would equate to an average reduction of £126 and a £3.36 billion annual cost to the taxpayer.

Expand and increase the Warm Homes Discount. We recommend that the existing Warm Homes Discount which currently provides a rebate of £140 to 2.2 million low-income families be increased by an additional £400 and to be paid automatically to an expanded 8.5 million households in receipt of either Pension Credit or working-age benefits. This increase will need to be funded by the government through general taxation, rather than being redistributed across energy bills as is currently the case.

In total, these measures would cost the exchequer £6.69 billion pounds for the year (£3.36 billion for moving legacy levies into general taxation and £3.33 billion for the increase and expansion in the Warm Homes Discount).

2. Apply a windfall tax on North Sea oil and gas

We propose applying a windfall tax of at least 10 per cent on profits from North Sea oil and gas. This would increase the current tax rate from 40 per cent to 50 per cent for 2022/23. We estimate this would raise revenue of approximately £1.2 billion pounds this year. The government should consider applying a similar or slightly lower charge in 2023/24 depending on the level of energy prices and oil and gas company profits at the time.

Such a move would not be unprecedented, with similar taxes applied during the First World War, by the Thatcher-led Conservative government in the 1980s on UK clearing banks and a ‘special tax’ on North Sea oil and gas, and by the Labour government on the privatised utilities in the late 1990s.

The claims by the oil and gas industry that such a move “would cause irreparable damage to the industry” are simply not credible. As Dale Vince, the chief executive of energy supplier Ecotricity has said, North Sea oil and gas companies are getting “paid at nine times more than they were last year” and the chief executive of BP recently described his company as a “cash machine” as it reaps the rewards from soaring energy prices.

Looking to the long-term

Prices are running high on our gas supply

Critics of the drive to net zero have been quick to point the finger at the green transition as the culprit for the energy bill crisis. Yet as Fatih Birol, the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA) has said, this is not “a renewables or a clean energy crisis; this is a natural gas market crisis”. Wholesale gas prices have surged worldwide - reaching a record 450p/therm in December 2021, compared to 50p/therm the year before - driven by a set of factors that have hit the natural gas sector.

These include the speed of the economic rebound after the pandemic, outages and upkeep of key gas infrastructure, and reductions in gas supply from Russia to Europe driven by Russia’s state-run gas supplier (estimates suggest that Russia could increase deliveries of gas to Europe by at least one-third).

As Birol argues, while this has been a crisis of natural gas there has been an impact on electricity markets particularly in Europe which rely on gas as a marginal fuel. Analysis by Carbon Brief suggests that 87 per cent of the increase in the UK cap this April will be due to wholesale prices, with most of the remainder due to the cost of supplier failure (29 suppliers have failed in the UK so far and counting).

Thus, while superficially attractive, the suggestion that the UK should increase the domestic supply of gas would be self-defeating, not least because it fails on its own terms – it wouldn’t reduce overall volatility in the price of gas. The truth is that the UK simply can’t recover enough gas to have a material impact on wholesale gas prices which are dictated by large global dynamics.

The National Audit Office, the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy and the Committee on Climate Change have all concluded, for example, that shale gas production would have next to no impact on energy bills. As a case in point, Norway is the 7th largest producer in the world and hasn’t been immune from rising energy bills. Increasing the supply of UK domestic gas would not have a material effect on bills.

In addition, any minor difference it could feasibly make would not be quick. Increasing production would require exploring new gas resources that would take years to develop. The average period from the first discovery of gas to first production from a field is 28 years.

While short term interventions to support household incomes is essential, the government must also act to improve the UK’s energy security, affordability, resilience and accelerating our path to net zero.

3. Invest and reform for the long-term

Launch a new ‘GreenGo’ scheme, investing in clean heat and energy efficiency to reduce demand. The government’s failure to sufficiently invest in insulation and clean heat measures is already costing households dearly as outlined above. The IPPR Environmental Justice Commission proposed that the government introduce a one-stop shop, known as ‘GreenGO’, where people can access financial support for the changeover, backed by up to £18 billion in public funding over the next four years.

Invest in clean energy and reduce gas subsidies. The government has already made a commitment to decarbonise the electricity grid by 2035. As others have argued, if the UK is to avoid continuing to pay a heavy price for having failed to accelerate towards clean energy, it must ramp up investment and policies in renewable power including onshore wind and solar, and adopt policies to support flexibility and storage.

Reform the energy market. As Citizens Advice have argued, the energy regulator Ofgem “allowed unfit and unsustainable energy companies to trade with little penalty”. They like many others are calling for energy market and regulatory reform not least to better protect consumers in future.

Authors:Luke Murphy, Joshua Emden and Henry Parkes

Methodology

The fuel stress figure is calculated as follows:

Cost increases based on raising the average household standard variable dual fuel tariff to the new price cap limit of £693. This cost increase is then applied across different income deciles’ expenditure on fuels (according to ONS 2021) and adjusted according to the differing costs associated with different energy efficiency ratings (ONS 2022). Expenditure is based on FY2019/20. Government proposals are included after calculating price cap increases as a blanket £350 reduction across all deciles (£200 from an energy bill rebate and £150 from a Council Tax rebate) – this does not show how many households are in each energy efficiency group but does highlight that every household in the lowest income decile would be likely to spend between 10-19 per cent of their income on energy bills even after government support. In the lowest income decile, income is assumed to be equal to expenditure.

Related items

Will technology reduce the cost of delivering public services?

This is the third in a series of blogs related to IPPR Scotland’s project on ‘Employment, Productivity and Reform in the Scottish Public Sector’ funded by the Robertson Trust.

The full-speed economy: Does running a hotter economy benefit workers?

How a slightly hotter economy might be able to boost future growth.

Making the most of it: Unitarisation, hyperlocal democratic renewal and community empowerment

Local government reorganisation need not result in a weakening of democracy at the local level.