Freezing the energy price cap could fight inflation and support households

Article

Summary

Politicians and commentators have raised the prospect of freezing or reducing the energy price cap this October to help shield households from the impacts of rising energy costs. Less explored has been the role of such a measure, what we call ‘a fiscal price cap’, in fighting inflation.

In this blog, we show how ‘fiscal price caps’, setting an upper limit for the energy price, subsidised through fiscal policy, could reduce inflation, and help prevent it from becoming embedded. As well as protecting household incomes in the short-term and reducing inflation, such an intervention could make a decisive contribution to the UK’s macroeconomic stability. This makes the idea worthy of serious consideration by policymakers, but as we highlight below, such a policy must be considered carefully and not viewed as a catch all solution.

The case for fiscal price caps

One of the overwhelming current priorities for macroeconomic policy is to bring inflation down as quickly as possible. High inflation seriously damages the economy, jobs, and real incomes – with those on low incomes hit the hardest. UK inflation is currently mainly driven by energy, goods and food inflation – all of which are primarily up due to global drivers. However, there is a risk that - with inflation reaching as high as 13 per cent this year - these price increases will, through second round effects, spread to other goods and services even more so than they have so far. This would increase the risk of high inflation becoming embedded into everyone’s expectations. It could stop inflation being “transient” and could lead it to becoming “persistent”. This would be disastrous.

Monetary policy, in the form of interest rate rises, is the traditional policy tool to manage inflation expectations. It has an important role to play. But it operates with lags, with little immediate impact on today’s inflation. Moreover, leaning exclusively on the monetary policy tool of raising interest rates alone has two key drawbacks: 1) to be effective on its own it would require abrupt rate rises that lower economic growth, exacerbating the now-forecast recession and 2) this leads to further falls in household income, especially for low earners, worsening the cost-of-living crisis.

A less often discussed, but potentially hugely important, macro-economic policy lever is to use fiscal policy to reduce prices immediately – we call this fiscal price caps. France for example has almost entirely limited increases in energy prices through such measures. Doing so could be beneficial for keeping inflation low not just now, but also in the future.

Recent research backs this up. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) has shown that when inflation reaches a high level this means prices move more in tandem. This means that price and wage setting in one industry responds more to what is happening in other industries. Particularly high levels of this occur in advanced economies when inflation exceeds about 5 per cent. Different economic players at this point increasingly form joint high inflation expectations. In other words, this research suggests that the higher inflation is today, the higher the likelihood that it will spread across the economy and remain high.

The upshot of this is that if fiscal policy is used to stop inflation exceeding a certain value in the first place, this could also help keeping it down in the future. In the remainder of this blog we explore some illustrative scenarios for how this could be done.

Inflation impacts of freezing or reducing the energy price cap

Rising inflation is already causing immediate damage to households across the UK - half of the UK population have cut back on food. Recent estimates of the energy price cap – a mechanism that limits the fluctuation of energy prices faced by households – could go up again, by 82 per cent this October (a threefold increase since the beginning of last year), and by a further 19 per cent in January 2023.

The Bank of England now estimates UK inflation rate to peak at 13 per cent. As a result, British families face a once-in-a-generation fall in their real incomes. And forecasts that inflation will not fall back to its 2 per cent target until 2024.

As we suggest above, the higher inflation rises the longer it lasts and the greater the pain to bring it back down.

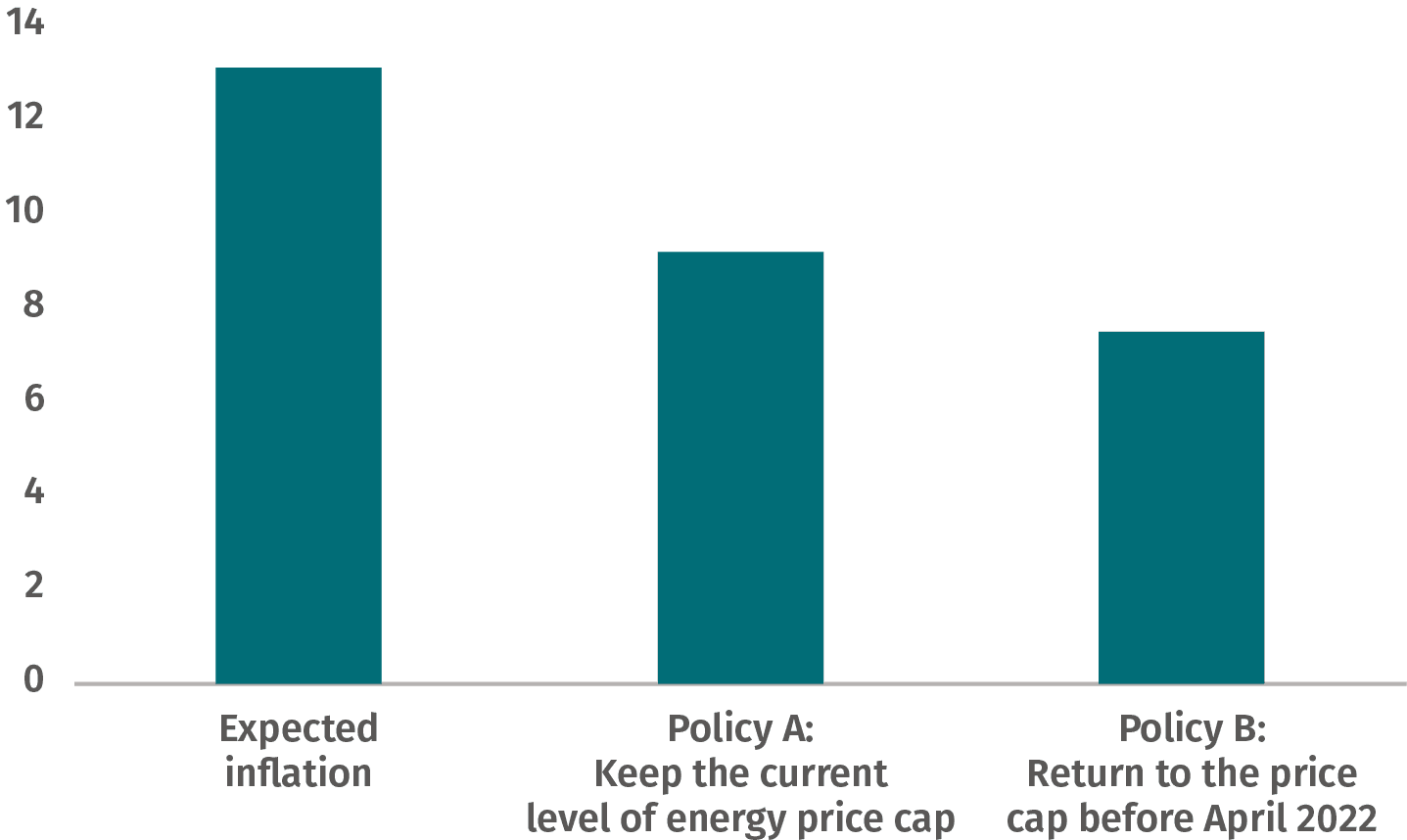

However, if the government were to hold the energy price cap at its current level, as others have argued, it could then reduce inflation this year by 3.9 percentage points, keeping inflation peaking at 9.2 per cent, instead of 13 per cent (see Figure 1 and Policy 1 in Table 1). This could make a significant contribution towards keeping overall inflation in check in the future.

Figure 1: Keeping the price cap at the current level could reduce inflation by 3.9 percentage points

Inflation impacts of freezing or reducing the energy price cap, per cent inflation, year on year, at Q4 2022

Source: IPPR analysis of Bank of England (2022), ONS (2022), Ofgem (2022).

Table 1: Reducing the energy price cap to its November 2021 level could cut inflation by 5.6 percentage points

Impact on expected year-on-year inflation in Q4 2022 of freezing or reducing the energy price cap

Detail | Direct inflation change from the policy (percentage points) | Inflation increase from higher aggregate demand if fiscal price cap is not tax financed (percentage points) | Net inflation impact (percentage points) | |

Policy 1: maintain energy price cap | Cap the energy price at the May 2022 level | - 4.2 | 0.3 | - 3.9 |

Policy 2: lower energy price cap | Return the energy price cap to the November 2021 level | - 6.0 | 0.4 | - 5.6 |

Source: IPPR analysis of Bank of England (2022), ONS (2022), Ofgem (2022).

Note: See technical annex for methodology. The inflationary impact of higher demand is based on the Bank’s June Monetary Policy Summary estimates – we consider it a lower bound. This is why, below, we would suggest offsetting much of the of the policies through windfall and other taxes.

A larger still inflation reduction could be achieved by reducing the energy price cap back to the level at the end of 2021. The net effect would be a 5.6 percentage point reduction in inflation (Table 1). These calculations take into account the countervailing effect of fiscal expansion if these measures are not financed by taxes but by additional borrowing (see appendix for methodology). If, as we suggest below, the policies are at least partly funded through e.g. windfall taxes, inflation could be reduced by a further 0.7 and 0.9 percentage points respectively.

If the UK government did pursue this policy, it would not be alone. About half of European economies have some form of price limiting measure in place. The French government has frozen gas prices and limited electricity increases to 4 per cent, with an estimated cost of €38 billion. And indeed, the UK government itself has already passed a £400 energy bills reduction. It could build on this approach.

Similarly, the fiscal price caps approach could be expanded to other sectors of the economy. For example, the UK government could reduce prices for public transport (rail and bus fares) in a similar way to Germany (who are offering a €9 per month flat rate ticket for regional public transport, nationwide). According to one estimate, this reduced rail ticket prices by 90 per cent. We estimate that if the UK reduced public transport costs by 50 per cent, this would reduce inflation by a third of a percentage point.

One counter-argument against the use of price caps is that preventing full price adjustments are an inefficient tool to protect the low-income households and prevent stronger behaviour changes, including by incentivising people to replace their gas-fired domestic heating systems. While this argument is crucial in the long term in the short-term these incentive arguments are less convincing.

First, energy prices are already 73 per cent higher now than they were in Q1 2021 – a strong incentive to transition away from gas already exists. Second, incentives only work if households can quickly transition to low-carbon homes. The government’s lack of support for this is currently the key bottleneck and needs to be unblocked.

Whatever policy approach the government takes in the short term, it urgently needs to scale up its strategy for, and investment in, clean energy and the delivery of heat pumps and insulation in the UK.

Policy considerations for freezing or reducing the energy price cap

While there are clear benefits to this policy, there are also important trade-offs and wider implications for those looking at this policy to consider.

Who is being supported: Our calculations above assume that all households are covered for the average annual utility bill. However, different types of coverage are conceivable. For instance, the energy price cap could only apply to low-income households, or only up to a certain amount of usage. Both could significantly reduce cost, though could lessen the inflation-reducing effect as not all prices for everyone would be capped. Coverage could also be broadened for example, if some or all businesses were covered. High energy costs faced by businesses are likely to be feeding into non-energy price rises. It’s also important to note that other targeted support may still be necessary through the benefits system to support households on low incomes who have not received adequate support for previous increases in the energy price cap or who are already suffering from the secondary impacts of inflation.

Costs: We estimate that holding the level of the price cap where it is now would cost about £45 billion and reducing it to the October 2021 would cost £60 billion (cutting public transport fares by 50 per cent would cost £12 billion). While a significant sum of money, it is comparable to Liz Truss’ proposed £50 billion tax cuts and spending plan for the economy.

Who pays: The government could subsidise, through the public purse, the entire difference between the price cap and the true cost to energy retailers but this would largely involve subsidising the profits of energy producers who are making record profits. One of the attractive aspects of using fiscal (over monetary) policy to counter inflation is that instead of the cost being inevitably born by those on low incomes, government can choose which groups bear the burden via targeted taxation or other policies.

Regardless of the approach that the government takes to supporting households with their energy bills, it could act rapidly to close the investment allowance loophole and increase the rate of the existing windfall tax on oil and gas producers as well as potentially expand it to other sectors reaping windfall profits (as argued elsewhere by IPPR). Reforming the UK’s unequal taxation of wealth and income could be another approach to raising the funds to pay for freezing the energy price cap (Nanda & Parkes 2018).

Duration of the policy: According to current forecasts, energy prices are likely to continue to stay elevated (Figure 2). Indeed, according to the IEA (2022) gas prices could remain well above their 2021 levels until 2025.

Figure 2: Average energy bills are likely to continue to stay elevated into the new year

Actual and estimated average energy bills (£ annually)

Source: Ofgem and Cornwall Insights (2022).

This implies that there may be a case to keep a cap in place for an extended period. However, as outlined above, there are significant costs to this approach. Instead, it could be better to use the time provided by a one-year freeze to put in place a ‘social-tariff’, a measure designed to cap or reduce energy bills for those on the lowest incomes, and accelerate a programme of clean energy and reducing energy demand through home retrofit (though the benefits of the latter two policies will take time to come to fruition). If a cap were kept in place for an extended period, to keep costs in check it would be crucial to fund them at least partly through windfall and wealth taxes to maintain fiscal space for other priorities.

Conclusion

As politicians and policymakers debate the different options for supporting households through the energy crisis, it is clear that ‘fiscal price caps’ should be a serious option for consideration. But any proposal must also go hand in hand with a serious plan to ensure that there is enough support on an ongoing basis to support those on the lowest incomes and to reduce our reliance on expensive gas by accelerating the transition to renewables and reducing energy demand through a national retrofit programme.

This is in addition to (1) cyclical factors and (2) structural factors. Cyclical factors are ‘how hot’ the economy is running, with fast growing economy being associated with more inflationary pressures. Structural factors in turn are long-term changes such as globalisation, which exposes countries more to global conditions. Another crucial structural condition is the power of labour and companies. Since the 1970s bargaining power of workers (including through unionisation) has declined significantly meaning they are less able to reap the benefits of a hot economy (and its implications or inflation). At the same time power of businesses has increased since the 1970s and they are relatively more able to reap the benefits of a hot economy.

And it is possible that it could rise further, depending on what happens to non-energy prices, including food.

Carsten Jung is senior economist at IPPR, Luke Murphy is associate director for energy and climate at IPPR, Dr. Jeevun Sandher an economist at King's College London, and Milad Sherzad an economics and politics student at the University of Edinburgh

The analysis behind this blog was kindly supported by the Economic Change Unit.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.