Level playing field – IPPR Brexit briefing

Article

Last updated 08/06/2020

With the deadline for extending the transition period approaching, the negotiations between the UK and the EU on their post-Brexit relationship are entering a critical stage. Both sides have now published their proposed texts for the negotiations and it is clear there are a number of areas of major divergence. One of the most contentious areas so far – which has led to an acrimonious war of words between chief negotiators Michel Barnier and David Frost – is the negotiations on the ‘level playing field’. This briefing explores what the level playing field is and where both sides currently disagree.

The joint aim of the UK and the EU in the negotiations is a free trade deal that guarantees no tariffs or quotas on traded goods. As the quid pro quo for a tariff-free, quota-free deal, the EU has made clear it expects a ‘level playing field’ for trade in order to prevent the UK from gaining an unfair competitive advantage over member states. The EU argues that this is because of the size and proximity of the UK and the close trade links between the two territories.

For the UK government, such level playing field measures are proving difficult to accept, given prime minister Boris Johnson’s insistence that the future agreement cannot include any requirement for the UK to continue to follow EU rules or be subject to the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The UK has suggested that it would be willing to lower the ambition of the agreement – by accepting tariffs on certain goods in return for concessions on the level playing field. But the EU has said that it will expect a level playing field regardless of whether the deal “covers 98% or 100% of tariff lines”. This has resulted in a major stand-off between the UK and the EU on the scope and enforcement of the ‘level playing field’ for post-Brexit trade.

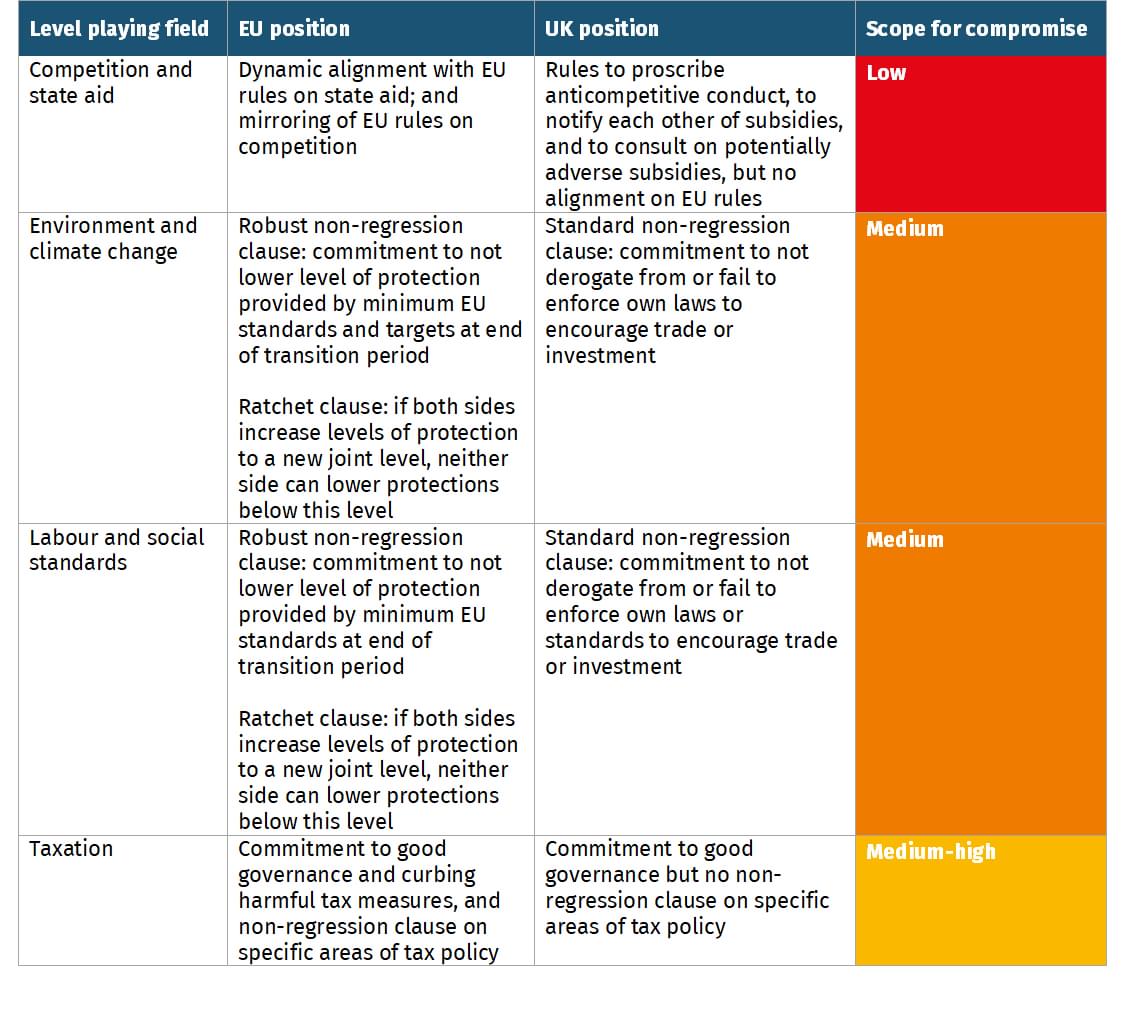

Within the political declaration, the UK and the EU have agreed to make ‘level playing field’ commitments in four areas: state aid and competition policy, environmental protections, labour standards, and taxation. The proposed negotiating texts of each side, however, are far apart. Below we summarise the positions of both sides and assess the potential for compromise in each area.

State aid and competition policy

The EU has taken the most robust position in the area of state aid and competition policy. The EU’s draft legal text states that the UK will continue to align with EU state aid rules. According to the text, this is to be enforced in the UK by an independent authority (i.e. the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority) with the close oversight of the European Commission. In order to administer the agreement, the EU text states that disputes on state aid between the two sides should be subject to the standard dispute resolution procedure – that is, they should first be dealt with through consultations, and then if necessary be escalated to a formal arbitration panel. This could result in the offending party facing sanctions – such as financial penalties or restrictions in market access. In addition, any questions relating to the interpretation of EU law would have to be decided by the Court of Justice of the European Union. In the short-term, there is also the further option for the EU to unilaterally take interim measures where it believes the UK has breached the rules in certain situations.

Based on its draft text, the UK is taking a very different approach. The UK’s legal text contains broad commitments on proscribing anticompetitive conduct and on regularly notifying each other on subsidies. It also includes a consultation mechanism to discuss subsidies that could have a negative impact on the interests of the UK or the EU. But this consultation process is very different from the strict alignment envisaged by the EU’s negotiating position, and it would for the most part not be subject to formal arbitration or sanctions.

However, it is important to note that the UK-EU withdrawal agreement includes specific provisions on state aid for Northern Ireland. According to the withdrawal agreement, the UK must continue to follow EU rules on state aid relating to any state aid measure that affects trade between Northern Ireland and the EU. Moreover, these rules will be supervised and enforced directly by the European Commission and the CJEU. The UK has therefore already agreed to follow state aid rules for trade respecting Northern Ireland – a significant concession in the context of the wider level playing field.

Environment and climate change

In the joint political declaration, the UK and the EU provisionally agreed to uphold the level of environmental protection provided by existing common standards – i.e. the current minimum EU standards. However, since then both parties have hardened their stances.

The EU’s draft legal text includes a non-regression clause that that requires the UK to maintain the level of environmental protections provided by minimum EU standards and targets at the end of the transition period (i.e. 31 December 2020). This does not mean that the EU expects that the UK must align to its rules; instead, it means that the UK’s level of environmental protections should not fall below current levels. But the text also includes a ‘ratchet clause’ which ensures that, in the scenario where UK and EU levels of protections both increase, this joint new level of protection becomes the new benchmark which must be maintained. That is, if the UK and the EU both choose to improve their environmental standards up to a new level of protection, the UK cannot then reverse its choice and reduce its level of protection below this new level in future.

The EU text specifies the relevant areas of environmental policy in scope – including access to environmental information, environmental impact assessments, industrial emissions, air quality, nature conservation, waste management, water protection, chemicals, and food safety. (A separate non-regression clause covers climate change commitments.) It also requires the UK to create an independent body to monitor and enforce the environmental commitments. Finally, according to the EU text any disputes on the environmental commitments are subject to the standard process of dispute resolution – that is, if necessary they can be brought to an arbitration panel and lead to sanctions for non-compliance.

The UK text, for its part, replicates the text of CETA, the EU-Canada agreement. This includes a non-regression clause that states that neither party should derogate from or fail to effectively enforce their own environmental laws in order to encourage trade or investment. This is much weaker than the EU’s proposals: it contains no ratchet clause, no general requirement to maintain levels of protection, and no precise list of policy areas. Moreover, it only applies when either party can demonstrate that any fall in standards encourages trade and investment. Finally, the UK wants to exclude these commitments from formal dispute resolution and therefore eliminate the possibility of sanctions in the case of non-compliance.

Labour and social standards

As with environmental protections, the UK and the EU at first provisionally agreed to negotiate a commitment to uphold common standards in the area of labour and social policy, but their positions have diverged since then.

The EU’s draft legal text now includes a non-regression clause that would prevent any backsliding from the level of protection provided by minimum EU labour standards at the end of the transition period, as well as a ‘ratchet clause’ to ensure that where both the UK and the EU improve their protections they cannot backslide from their new joint level of protection. The list of areas of labour and social policy specified by the EU includes fundamental rights at work, occupational health and safety, fair working conditions, and information and consultation rights. The EU text requires the UK to enforce the non-regression clause through the UK’s own domestic authorities, including an effective system of labour inspections. For disputes relating to how the labour rules are enforced, the normal dispute resolution measures apply – and therefore potentially the use of arbitration panels and sanctions for violating the rules.

On the other hand, the UK’s proposal is identical to the labour non-regression clause in CETA – ie an agreement to not derogate from or fail to enforce one’s own labour laws or standards as a means of encouraging trade and investment. This is far weaker and less precise than the EU’s proposals. The UK text also excludes the provisions from standard dispute resolution – therefore preventing formal arbitration or sanctions in the event of a dispute between the two sides.

Taxation

In the area of taxation, the EU legal text includes commitments on the principles of good governance and curbing harmful tax measures. Alongside these, it includes a non-regression clause relating to specific areas of taxation policy – in particular, exchange of information, anti-tax avoidance measures, and country-by-country reporting.

The UK text, for its part, also includes commitments to principles of good governance, but has no reference to a non-regression clause on tax matters.

In summary, the proposed legal texts of the UK and the EU suggest major differences in the area of competition and state aid, where the EU is seeking continued alignment with EU rules and the UK is seeking scope for regulatory divergence. On taxation, there are some differences, but there is also a degree of consensus on the core principles of good governance, and this issue is less contentious than other elements of the level playing field.

On labour and environmental protections, the UK and the EU have hardened their positions and there now appears to be a significant gap between the two sides. However, there is still scope for compromise. The original version of the withdrawal agreement negotiated by Theresa May’s government included robust non-regression clauses – more stringent than typically used in free trade agreements (i.e. the UK position) but without the additional demands of a ratchet clause that would take effect over time (i.e. the EU position). This could therefore be a sensible landing zone for the negotiations.

A summary of the expected UK and EU positions and the potential scope for compromise are below.

Resources and Contact

- The 2019 research paper State Aid Rules and Brexit is available to download here: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/state-aid-rules-and-brexit

- IPPR public attitudes polling on Brexit, trade deals and state aid from 2018 is available to download here: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/have-your-cake-or-eat-it

- More information about Marley Morris is available here: https://www.ippr.org/about/people/staff/marley-morris

Briefing author Marley Morris is available for broadcast and print interview on the level playing field, immigration and the UK-EU trade negotiations. To arrange an interview, please contact Digital and Media Officer Robin Harvey r.harvey@ippr.org

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.