Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups at greater risk of problem debt since Covid-19

Article

Before Covid-19, around 4 per cent of households in the UK were identified as having ‘problem debt’ (ONS 2019a); that is, debt which represents a high proportion of disposable income, includes arrears on household bills or credit commitments, and feels like a heavy burden to the people who owe the money. Unlike the manageable credit that has become a standard part of modern life, problem debt is not evenly distributed across society. It is more common in households with low and precarious incomes, and with lower levels of household wealth.

And for these households, getting into debt increasingly reflects a toxic combination of low income and high fixed costs (such as housing, utilities, food and essentials), making it hard to avoid debt even when life is lived very frugally (Matin and Lane 2020). An income shock, such as redundancy or a sudden reduction in earnings, can be enough to tip the balance from ‘'’just about managing’ to ‘just not managing’ for a household that is trying hard to get by on not very much money.

This does not bode well for poorer households in a year that has brought the most dramatic income shocks this country has seen for decades. Covid-19 has already brought hardship to many families. The prospect of a second lockdown, coupled with rising levels of unemployment and the end of the current furlough scheme at the end of October, are all likely to drive up overall debt levels, and problem debt. While some households have taken the opportunity to save money and pay down debt since March (with reduced costs of commuting and fewer opportunities to spend), others have seen their wages fall, their jobs come to an end, and their opportunities to earn and work dwindle.

Debt is not just a financial challenge; it also has serious impacts on health and wellbeing, and its long-term effects can be devastating. With the UK one of the most regionally unequal countries even before the crisis, the path of Covid-19 infections has entrenched existing inequalities. Too often the people who were already most vulnerable, including those with underlying health conditions, low incomes, and poor or insecure housing have been hit hardest.

A particular feature of the crisis has been the disproportionate impact of the disease on people from black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) communities. New research from IPPR suggests that these groups may also be particularly vulnerable to increased debt and financial hardship as a result of Covid-19 and the economic lockdown. This in turn may reflect long-term inequalities such as the ‘ethnicity pay gap’ (ONS 2019b) and unequal access to employment; these may make it harder to build up a financial ‘safety net’ of savings and wealth through higher earnings.

The pre-crisis picture

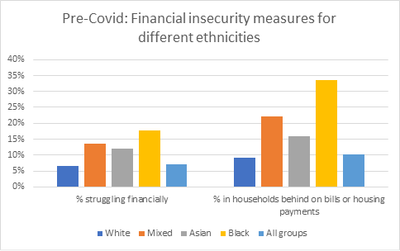

Before Covid-19, ethnic minority groups were more likely to say that they were ‘struggling financially’, and to live in a household which was behind on bills or housing payments.

Seven per cent of people across the population reported that they were struggling financially, but for people from non-white groups the figure was between 12 and 18 per cent.

A similar picture emerges for the proportion of people living in households behind on bills or housing payments. Across the UK population, one in 10 people were in this position before the crisis; however, for people from mixed ethnic groups, the proportion who reported this was double that. And among people from black communities, more than a third were living in households that were behind on bills or housing payments.

Figure 1: Ethnic minority groups were more likely to experience financial insecurity pre-crisis

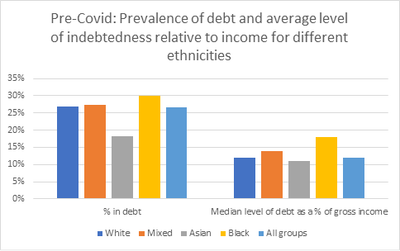

Pre-crisis, however, this greater financial vulnerability for black, Asian and minority ethnic groups did not translate into a generally higher likelihood of holding debt. Overall levels of debt-holding were relatively similar for people from white, mixed and black groups but lower for people from Asian communities. Among households with debt, levels were highest for people from black communities (when debt is measured as a percentage of gross annual income).

Figure 2: The formal debt picture among ethnic groups is much more similar

The impact of Covid-19 on ethnic minority employment

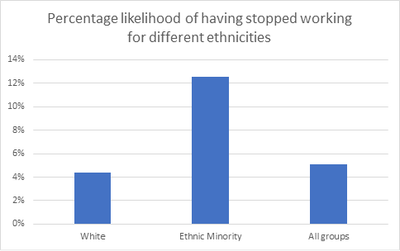

Our analysis of the Understanding Society Covid survey in June suggests that employees from black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups are considerably more likely than the population as a whole to have found themselves out of work as a result of the crisis. This represents a substantial ‘income shock’ for many households and individuals.

Although sample sizes do not allow us to do more granular breakdowns, our analysis shows that overall:

- Across the population, around 5 per cent of those employed in January/February were no longer working in June

- Amongst ethnic minority groups, the equivalent figure was 13 per cent. As such, they were nearly three times as likely to have moved from employment to not working.

Figure 3: Ethnic minorities appear to have been far more likely to have stopped working in the crisis than average

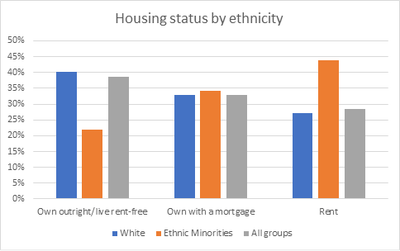

People from black, Asian and minority ethnic groups are also likely to be particularly vulnerable because they are more likely to rent than to own their home. Rates of renting are substantially higher for these groups than for the population as a whole. This matters for financial security and indebtedness as it means that as a group, they will have been less likely to take advantage of mortgage holidays and more likely to have built up rent arrears during the crisis.

Figure 4: Minority groups are more likely to be renters, and less likely to own their own homes - limiting their scope to reduce costs in face of an income shock

Borrowing behaviour during the Covid-19 crisis

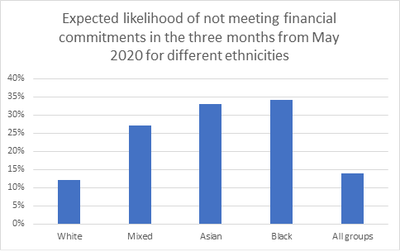

According to the ‘Understanding Society’ survey, black, Asian and other minority ethnic people feel that they are at greater risk of falling into arrears due to the pandemic. In May, the Covid-19 survey asked participants to rate on a scale of 1 to 100 the likelihood that they would have difficulty paying their usual bills and expenses in the next three months (from May 2020). The average likelihood rating given by respondents is shown below. This suggests that black, Asian and minority ethnic people are considerably more concerned about being able to make ends meet as the crisis progresses.

Figure 5: Ethnic groups and their views on the likelihood of not meeting financial commitments in the next three months.

Conclusions

This new research from IPPR offers an early warning of a further impact of Covid-19 on already entrenched inequalities in the UK. It highlights the importance of ensuring that there are socially and culturally sensitive debt support services, grounded in local communities and responsive to a rapidly changing context in local economies and housing markets. Not only will this crisis place an additional pressure on these services; it has implications for housing providers, local authorities, and community and voluntary organisations, particularly in areas of higher deprivation. At a time when local finances have been squeezed sharply as a result of 10 years of austerity, and when social distancing requirements make face-to-face support more difficult, the need for proactive and targeted support has never been greater.

Methodological note: the data presented in this blog is IPPR’s analysis of the Understanding Society Survey Waves 8 and 9 (University of Essex 2020a), and the Understanding Society Covid Survey Waves 2 and 3 (University of Essex 2020b). Wave 8 covers the period January 2016 to June 2018. Wave 9 covers the period January 2017 to June 2019. Covid Wave 2 covers the period May 2020. Covid Wave 3 covers the period June 2020.

“White” here refers to people from both British and non-British groups.

References

Matin J and Lane J (2020), Negative budgets: A new perspective on poverty and household finances, Citizens Advice

ONS (2019a), Household debt in Great Britain: April 2016 to March 2018, Office for National Statistics

ONS (2019b), Ethnicity pay gaps in Great Britain: 2018, Office for National Statistics

University of Essex (2020a) ‘Understanding Society: Waves 1-9, 2009-2018 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009’, dataset

University of Essex (2020b) ‘Understanding Society: COVID-19 Study, 2020’, dataset

Related items

The full-speed economy: Does running a hotter economy benefit workers?

How a slightly hotter economy might be able to boost future growth.

Making the most of it: Unitarisation, hyperlocal democratic renewal and community empowerment

Local government reorganisation need not result in a weakening of democracy at the local level.

Transport and growth: Reforming transport investment for place-based growth

The ability to deliver transformative public transport is not constrained by a lack of ideas, public support or local ambition. It is constrained by the way decisions are taken at the national level.