Now is the time to confront UK’s investment-phobia

Article

With public investment well below the G7 average and business investment at the bottom of the league, the UK has little hope of breaking out of its growth doom loop without sustained investment.

Landing on earth for the first time and reading recent coverage of unpublished internal Treasury analysis of Labour’s green investment plans, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the UK economy suffers from too much investment. The Labour Party have committed to investing £28 billion per year in green jobs and industry but have recently said they would have to “ramp up” this investment. This decision is sensible given skills challenges and the time needed to get projects off the ground, however the idea, as critics claim, that investment on this scale would be bad for the economy is wide of the mark.

If the economy is the engine of a country, investment is its fuel. But the UK’s tank is running on empty and it’s harming economic growth, driving inequality, and slowing the pathway to net zero and energy security.

Investment – by private companies and by government – is critical to economic growth as it funds the physical equipment or the intangible software and training that are essential to producing goods and services and doing so more efficiently (increasing productivity). Investment is at the heart of the creation of good-quality, well-paid jobs, driving innovation and technological progress, and economic stability.

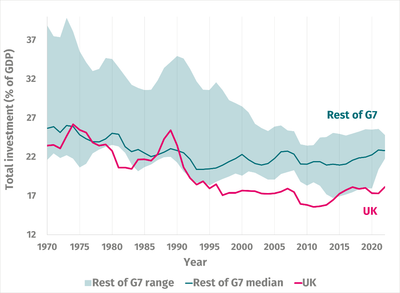

The UK has suffered decades of under investment. We consistently rank the lowest in the G7 and among the worst performers in the OECD club of 37 developed economies, and we are worse off than our competitors as a result.

We consistently rank the lowest in the G7 and among the worst performers in the OECD club of 37 developed economies.

Figure 1 – The UK has always underinvested but today is falling further behind

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD (2023)

Most urgently, lack of investment in green technologies is hindering our progress towards decarbonising our economy. This lack of action to spur makes it less likely that this country will capture the economic up-side; the domestic production in the industries of tomorrow. Green industries could be worth $10.3 trillion to the global economy by 2050 (5.2 per cent of global GDP) – now is the time to begin that investment if the UK wants a share of that prosperity and the jobs it will create.

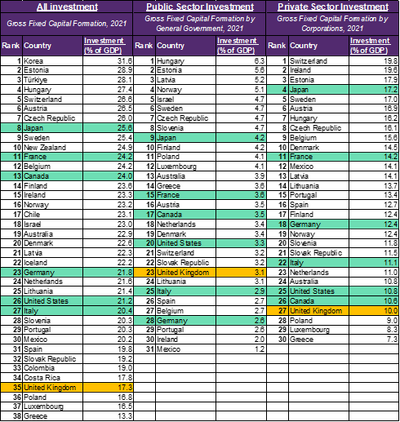

Red lights on the dashboard

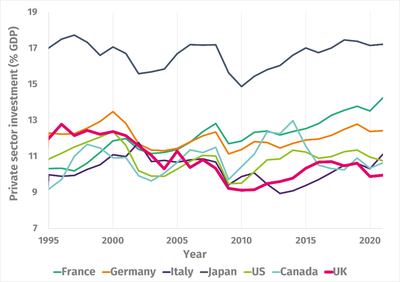

The last time the UK was above the G7 median level of investment as a proportion of GDP was in 1990. Business investment is lower in the UK than any other country in the G7 (figure 2). The UK fell to the bottom of the ranking in 2019, but other countries increased their levels of investment after the pandemic faster than the UK, further widening the gap. In 2021, the UK ranked 27th on business investment among the 30 OECD countries that we have data for, worse than every other developed economy apart from Poland, Luxembourg, and Greece (Table 1).

Business investment is lower in the UK than any other country in the G7.

Figure 2 – The UK has lower private sector investment than the rest of the G7 and is falling behind

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD (2023)

The last time the UK was the median country in the G7 for private sector investment was 2005. If the UK had remained in that median position, businesses in the UK would have invested an additional £354.3 billion between 2006 and 2021 in real terms (see methodology note).

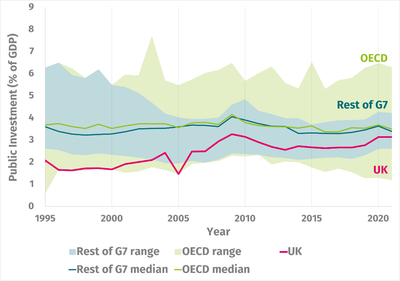

Public investment (by national, local, and devolved governments) is low and has never been above average for the OECD or the G7 (figure 3). If the public sector had been similarly average in the G7 over the same period, the British government would have invested an additional £208.4 billion in real terms. Combining public and private investment, this would total an additional £562.7 billion, or over half a trillion pounds over 16 years in real terms. For comparison, this would be 14 times the investment needed to build Northern Powerhouse Rail or HS3 (estimated cost £39 billion), or 30 times the cost of the Elizabeth Line (cost £18.8 billion).

Figure 3 – UK public investment is below average for the G7 or the OECD

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD (2023)

Criticisms of green investment are wide of the mark

The IPPR Environmental Justice Commission previously called for a £300 billion, 10-year green investment programme to deliver economic prosperity, create jobs, tackle regional inequality, and address climate change and nature’s decline (Environmental Justice Commission 2021). The UK’s consistent economic precarity and the global opportunity of the green transition underline the need for this investment, at pace. Yet calls for green investment on this scale have come under considerable fire.

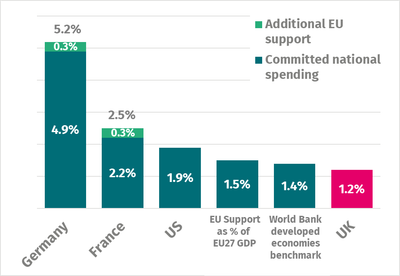

First is the notion that significant green public investment would make the UK an international outlier. In 2021, UK public investment was 3.1 per cent of GDP, and is projected to fall to just over 2 per cent in 2027/8. Analysis by IPPR shows that additional annual public investment of £30 billion (1.2 per cent of GDP in 2023/4) would still leave the UK below the most effective level of public investment that analysts have argued for (4.5 per cent of GDP). Moreover, the US and the EU are significantly stepping up their investment, with the UK falling behind in the global green race to net zero (figure 4).

Analysis by IPPR shows that additional annual public investment of £30 billion... a year would still leave the UK below the most effective level.

Figure 4: The UK now has one of the lowest proportions of spending to address climate change of many comparable global economies

Source: Reproduced from CBI 2023

Second is the idea that green investment would be fiscally irresponsible. IPPR estimates highlight that as slack in the economy widens, more fiscal support is possible while keeping inflation at bay. In 2024-25, both the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) and Bank of England project significant falls in inflation and increasing slack in the economy. Pairing investment with progressive tax rises – such as equalising taxes on income from wealth and income from work, or on share buybacks and dividends – could further ease inflationary pressures and create fiscal headroom in the medium term. We mustn’t learn wrong lessons from the Truss premiership – markets didn’t baulk at borrowing full stop, rather they recognised the difference between borrowing to fund tax cuts and borrowing to invest in productive capacity.

Third is the argument that borrowing is too costly or would raise interest rates. Assuming the quality of investment is maintained at a high standard and is phased in over time, a proposed annual stimulus of £30 billion, could be reconciled with a ‘falling debt to GDP rule’ by the fiscal year of 2027/28, as we show in Jung (forthcoming). This can be the case even in the presence of elevated interest costs because, even under conservative assumptions, public investment raises the productive capacity of the economy and boosts growth, raising GDP more than debt and interest payments. While a higher interest rate scenario slightly lowers this effect, we still find that the effect of public investment to be compatible with a stable or falling debt-to-GDP. Moreover, Cambridge Econometrics (on behalf of the CCC) have estimated that net zero will boost GDP by 2 per cent by 2030 and 3 per cent by 2050. The Treasury recognised this ‘growth dividend’ in the Net Zero review, showing that economic multipliers for investments in clean energy can be between 2.2 and 2.5 times larger than for fossil fuels.

Fourth is the idea that public investment will crowd out business investment. Rather, there is strong evidence that higher public investment is a core component of enabling private investment, and raising GDP. Public investment can “crowd in” private if it fosters expectations of areas of future growth and profit for firms. For this reason, public investment should be well directed towards strategic industries (i.e. green sectors) to positively influence firms investment decisions. Public investment will be even more effective if it is planned in the long-term and stable, rather than volatile and unpredictable to businesses, as is frequently the case in the UK. Parts of the USA Inflation Reduction Act guarantee stability for 10 years, whilst the UKs new capital allowance scheme doesn’t even give certainty for 3 years.

Fifth, is the idea we can sit by and do nothing - there are in fact enormous costs of inaction. The impacts of the climate and nature crises are being felt now. Record temperatures in the UK, sustained drought, and flooding populates most summers. These have real costs to the economy. The OBR projects that public debt will grow to 289 per cent of GDP by 2050 with no further emissions reductions. In an early transition scenario, debt instead reaches “three per cent of GDP below the baseline in 2050/51”.

Lastly, is the idea that this is in tension with things that voters want. Climate action is popular, the vast majority of the public don’t think the government is doing enough, and polling on Labour’s pledge to spend £28bn a year on green technology shows it is popular across the population - people seem to understand the need to borrow to invest on this issue.

Conclusion

We need to break the doom loop of poor investment and poor growth. As a global race to the top on capturing the green industries of tomorrow kicks off around the world the UK needs to act now. The case for public investment in green industries, to catalyse investment by businesses, is overwhelming.

There are very real questions about how best to achieve value for money with public investment, what exactly it should be spent on, and the best mechanisms and institutions for spending. IPPR has set out elsewhere an approach that accords with five core principles: that it is fair, additional, phased, reforming, and efficient (also here, and here). Labour’s promise to phase in investment, as advocated by IPPR, is a sensible recognition of reality, but phasing it in as fast as possible, to achieve the maximum benefit, must be the goal.

What should not be in question is the need to significantly raise the level of investment in the UK economy, both public and private. It’s time for the UK to get over its investment-phobia.

Methodology notes

Where appropriate, “total investment” represents Gross Fixed Capital Formation, “private investment” or “business investment” represents Gross Fixed Capital Formation by Corporations, and “public investment” represents Gross Fixed Capital Formation by general government. The OECD dataset for GFCF by sector begins in 1995 so all international comparisons are from that date.

Real prices are calculated in 2019 prices relative to ONS data.

Table – Comparison of levels of investment for OECD countries

Source: IPPR analysis of OECD (2023)

Related items

The full-speed economy: Does running a hotter economy benefit workers?

How a slightly hotter economy might be able to boost future growth.

Making the most of it: Unitarisation, hyperlocal democratic renewal and community empowerment

Local government reorganisation need not result in a weakening of democracy at the local level.

Transport and growth: Reforming transport investment for place-based growth

The ability to deliver transformative public transport is not constrained by a lack of ideas, public support or local ambition. It is constrained by the way decisions are taken at the national level.