Covid-19: What’s the outlook for Scotland’s workforce?

Article

The Covid-19 crisis is like nothing we’ve seen for over 100 years. What started as a health crisis has now likely turned into an economic crisis beyond anything we’ve seen in peacetime. As we move through the peak of the first wave of this health crisis, we need to begin to look at some of the economic aspects to the crisis including the potential scale of the initial economic shock, and some of the people that might be most affected early on. We know the health, social and economic crisis will affect us all, but we also know it won’t affect us all equally. This blog marks the start of a series of outputs through our Rethinking Social Security in Scotland programme, as we attempt to look at what Covid-19 means for financial security in Scotland.

As this pandemic has taken hold, financial insecurity has been magnified for families across Scotland. First through an immediate threat to our health, the health of our loved ones, and our ability to go out to work. For workers reliant on statutory sick pay, the self-employed, and those reliant on income from the gig economy, the prospect of being too sick to work hasn’t just posed a serious risk to their health – but a grave threat to their financial security. Since then, what started as a public health emergency has rapidly evolved into an economic crisis, posing a systemic threat to jobs and livelihoods through lay-offs, lost work or reduced working hours. For families who were already under pressure, and those whose jobs and earnings are at greatest risk, the economic impact of this crisis is already being felt. A recent survey of households across the UK from the Standard Life Foundation found an estimated 50 per cent of households are feeling anxious about their finances.

With such large parts of the economy shut down, this is a different sort of crisis to what we’ve seen before. Here, we consider the potential short-term impacts for workers across Scotland and their resilience to a financial shock.

The outlook for Scotland’s labour market is far from rosy. Last month, in an entirely unprecedented move, the UK government’s Jobs Retention Scheme has stepped in to pay 80 per cent of wages across many parts of the economy, now extended to the end of June. For families and employers under pressure, the Job Retention Scheme has provided a lifeline on a scale never before seen in our economic history. There was significant demand across the UK; within 48 hours of the scheme opening, 2.2 million applications had been made by employers, and the total number of employees accessing the scheme is expected to rise to over 8 million over the coming weeks (Strauss and Giles 2020). Serious concerns remain, however, for the estimated four in ten people facing a significant drop in earnings, who don’t feel they will benefit from government support through either the Job Retention Scheme or the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (Standard Life Foundation 2020).

The scale of furlough and unemployment in Scotland

Based on the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) UK-wide forecast, we anticipate that 750,000 employees in Scotland will be enrolled on the Jobs Retention Scheme over the next few months. We anticipate a further 150,000 jobs in Scotland will be lost, as some employers fail to weather the crisis. However, these job impacts will not be evenly spread across Scotland as different sectors face very different prospects

We’ve mapped these potential impacts onto Scotland’s labour market to look at the scale of disruption across Scotland’s industries and workforce. With limited data on how this crisis is affecting the UK – or Scotland’s - economy, such scenarios can only be illustrative. Here, we’ve factored in estimates on expected output changes by sector from the OBR, with data on the composition of the Scottish workforce to arrive at the best estimates possible.

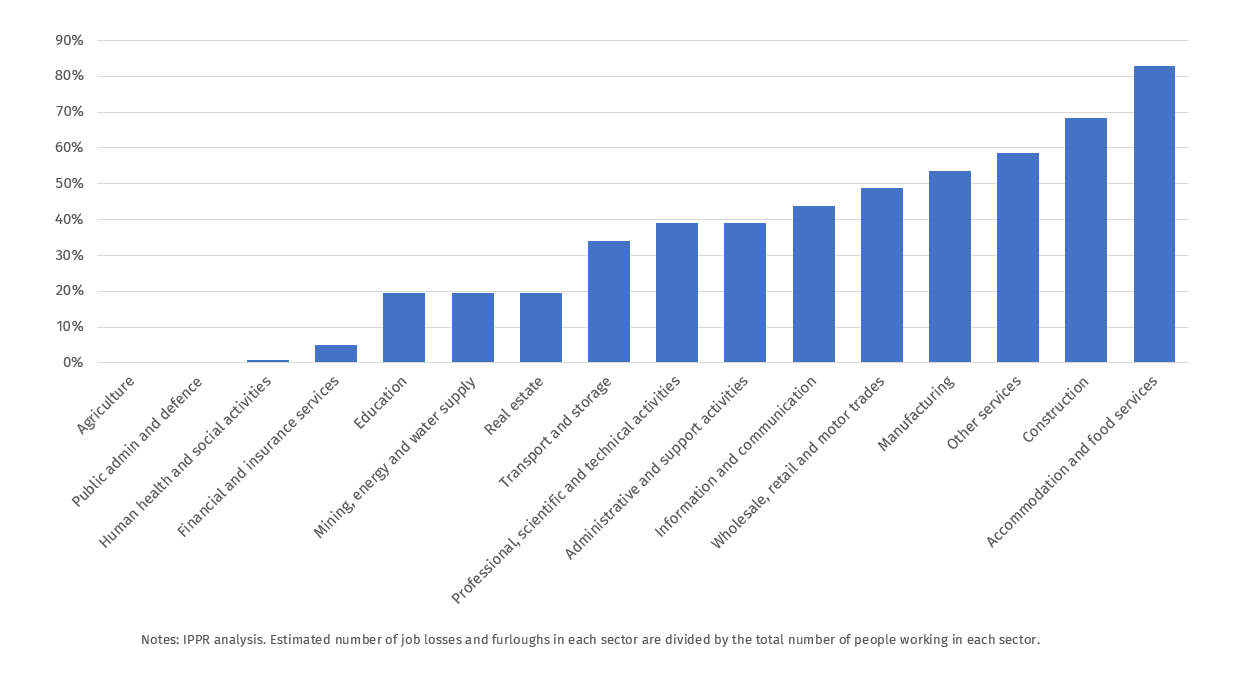

Figure 1: Estimated number of jobs lost and employees furloughed by industry

Across different sectors, we can expect disruption on varying scales. In retail and wholesale, Scotland’s largest employment sector outside of health, we forecast 31,500 job losses and 142,000 workers in Scotland put on furlough. In accommodation and food services, we can expect disruption on a similar scale: 31,000 job losses and 140,000 workers put on furlough. In the health sector, by contrast, we anticipate zero job losses and an estimated 14,000 jobs created.

Some of Scotland’s lowest paying sectors are those likely to be exposed to the most serious disruption over the coming months. In Scotland’s large hospitality and tourism industry (shown here as accommodation and food services), 83 per cent of workers are likely to be exposed to job losses and furlough (see figure 2). This is particularly concerning giving the prevalence of insecurity in these sectors going into this crisis, resulting from a combination of zero hours contracts, agency work and low pay. Accommodation and food services has the lowest average pay of any major sector in Scotland, with over 60 per cent of workers on low pay (less than two thirds of median weekly pay in Scotland – or £313.30). For these workers, a 20 per cent pay cut will not be easily absorbed. Analysis for the Fraser of Allander Institute has shown that most people employed in this sector are single adults, living alone. Without a financial buffer provided by another earner in the household, large portions of these workers could find themselves struggling to pay essential bills over the coming months, or being swept into poverty.

Figure 2: Estimated percentage of workers furloughed or jobs lost in Scotland, by industry, over the current quarter

In retail, despite high overall numbers of workers affected, due in part to the sheer size of the sector in Scotland, output is expected to fall much less dramatically than in hospitality, meaning that workers overall are at relatively lower risk. However, this does not mean that retail workers’ jobs are secure: nearly half of workers in this sector are likely to be affected by furlough or job loss and the proportion likely higher still in those lower paid customer facing roles. At the other end of the spectrum, the higher-paid finance and insurance sector looks to be relatively well insulated from the economic fall-out of Covid-19. This exposes a pattern across Scotland and the UK economy: workers with greater security and higher earnings are relatively insulated from the economic effects of this crisis, while the most precarious are likely to experience intensifying financial insecurity.

This is a rapidly changing picture as businesses await details of the Scottish government’s plans for a lockdown exit strategy.

Financial security going into the crisis

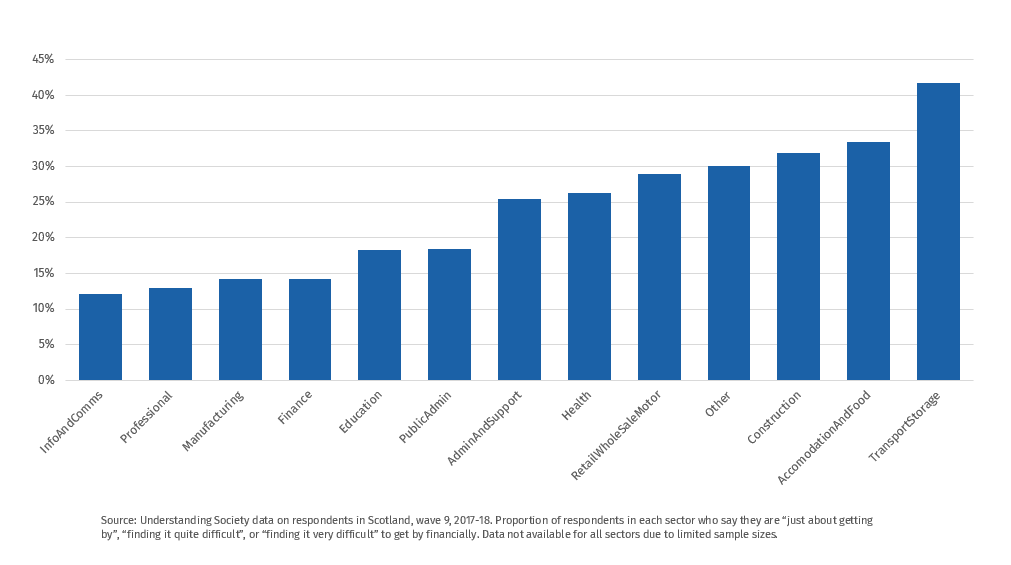

This picture is made all the more concerning if we look at how people working in the most affected sectors were managing financially prior to this crisis. Figure 3 shows the proportion of people working in each of Scotland’s major sectors who reported that they were “just about getting by” financially, or that they were experiencing financial difficulty. One in three workers in Scotland’s hospitality and tourism sector (shown here as accommodation and food) reported being under financial pressure, with nearly one in three workers in construction also experiencing financial strain.

Figure 3: Percentage of people working in each of Scotland’s major sectors just about getting by or experiencing financial difficulty prior to this crisis

For those working people already living with financial insecurity going into this crisis, the prospect of losing work or facing a cut in earnings and persistent insecurity through furlough will already be intensifying this insecurity. Against a backdrop of rising costs in food and energy bills, additional caring responsibilities and a greater risk of sickness putting additional strain on many families, it’s clear that workers at the sharp end of this crisis are under mounting pressure.

In Scotland, these effects are not likely to be felt evenly across the country. New RSA analysis published this week has looked at local economies across the UK that stand to be most affected by job losses, based on the industries work is concentrated in. At a local authority level, this analysis suggests that 10,074 jobs – or 32 per cent of local employment – in Argyll and Bute would be vulnerable. Meanwhile, none of the top 20 “safest” local authorities identified are in Scotland.

What happens after furlough?

Without question there are huge risks that once the emergency support is withdrawn and the furlough schemes end, whenever that may be, that a significant proportion of workers currently furloughed may face redundancy. This means that the UK and Scottish governments face a short-term crisis in household finances, which may become a medium-term one over the coming weeks and months. Whenever the emergency support ends we will need to see significant support continue to protect sectors and to protect many households across Scotland from extreme financial insecurity and hardship.

Before this crisis we believed the UK government had gone too far in pushing risk onto those that could least bear it. The Covid-19 crisis is beginning to show, in extreme form, the consequences of doing so. As we pass through what we hope is the peak of the health crisis and our focus turns to the economic fallout from the pandemic so far, we must use Scotland's powers to the full, and put pressure on the UK government, to provide an adequate safety net. The recent decision to double the Scottish Welfare Fund is a welcome example of action from the Scottish government to help keep families afloat. Over the coming weeks, governments at Holyrood and Westminster will need to take decisive steps to strengthen financial security to avoid some of worst case scenarios for households across Scotland and across the UK.

Henry Parkes is a Senior Economist at IPPR and tweets @HenryJParkes

Rachel Statham is a Senior Research Fellow at IPPR Scotland and tweets @rachelstatham_

Russell Gunson is Director of IPPR Scotland and tweets @russellgunson

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Standard Life Foundation for their support in funding IPPR Scotland’s Rethinking Social Security in Scotland programme. The Standard Life Foundation are an independent charitable foundation whose mission is to contribute towards strategic change which improves financial well-being in Scotland and across the UK. Their aim to work to see everyone to have a decent standard of living and have more control over their finances.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.