The government should scrap tax bands to revolutionise income taxes in the UK

The government should scrap tax bands to revolutionise income taxes in the UKArticle

Income taxes are never far from the centre of the UK’s national debate. This time last year, the Chancellor, Phillip Hammond, was preparing seemingly dry reforms to national insurance contributions (NICs) for his Spring Budget. Within days of being announced, the policies had become so politically charged they allegedly almost lost the Chancellor his job – and they were later mainly abandoned.

One year on, the Spring Statement may have changed its name, but Phillip Hammond remains at the Treasury’s helm and income taxes are still never far from the news headlines.

That’s not surprising, given that this area of policy is so important to the economy, family budgets and the governments public finances. Employee national insurance and income tax combined make up nearly 12% of GDP, absorb 13% of gross household incomes and account for 34% of total government tax receipts.

But our income taxes perform poorly against the most basic of tests: progressivity, work incentives and the capacity to increase revenues to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

The UK’s tax system as a whole is regressive when measured against family incomes in any given year. On average, the poorest 20 per cent of households pay 35 per cent of their gross income in tax, more than the average for all other households. Income taxes should be the main tool to improve this picture, but in fact, the government’s current plans are set to make things worse.

The Conservatives manifesto proposal to lift the personal allowance and higher rate threshold of income tax will see post-tax incomes for the richest 10% of families rise five times faster than for the poorest 10%.

The current system of allowances, rates and tax bands leads to perverse economic incentives. Earnings from work above £11,500 pay 32% after both income tax and employee national insurance are taken into account. But at the same time, earnings from dividends are charged at 7.5 per cent. For those on Universal Credit, the combined effect of tax and benefit withdrawal means some people keep just 25p from an increase in pay of £1.

The design and complexity of our income tax system also make raising revenue politically difficult. Variable rates for different types of economic activity, combined with abrupt ‘cliffs’ between tax bands, create groups of ‘losers‘ – whether actual or perceived – from most tax-raising proposals. This is precisely what the Chancellor found last year.

All three of these failings are structural in nature, and significant improvements cannot be made by tinkering with rates and allowances within the current system. If income taxes are going to better meet their goals, their very structure needs to change.

That’s why IPPR has published a policy report for the Commission on Economic Justice that proposes to do precisely that.

Our major reform has two elements.

First, all rates and allowance within income tax and employee NICs would be combined into a single schedule of tax rates, with different sources of income taxed at the same rate, and on the same terms. Income tax and employee NICs would no longer exist as separate taxes, but contributions to national insurance through the new income tax could continue on a similar basis as today, and could remain itemised on individual’s payslips.

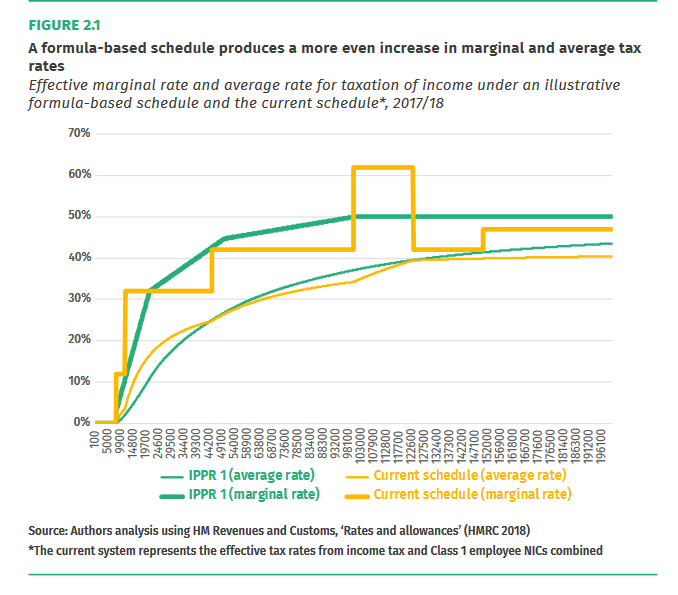

Second, the existing system of marginal tax bands would be replaced by a formula, such that everyone’s marginal tax rate would depend on their own precise level of income.

In effect, the current system of rates and bands would be replaced by a smooth and gradual increase in marginal tax rates as an individual’s income rises, between a tax free allowance at the bottom and a maximum rate of tax at the top. This would be similar to how Germany already manages part of its income tax system today.

Our illustrative modelling shows how such a system could reduce tax rates the most for the very lowest earners, increase financial work incentives for those on universal credit by up to 40%, and increase annual take-home for those on middle incomes by around £1,100.

In fact, such reforms have the potential to receive political support from a wide spectrum of taxpayers. Our results show that moving to such a system could give money back to 84% of taxpayers without costing government a penny, while raising taxes for the very richest by an average of less than 3 percentage points.

The new system would also make it much easier politically to raise income taxes to pay for public services. For example, all of the money needed to plug the annual NHS funding gap expected by 2020/21 could be found by an overall tax change which still gave small reductions in tax to 75 per cent of taxpayers.

Having been burned once, it’s unlikely that the present Chancellor will try his hand again at reforming income taxes sometime soon. But for a government of any colour wishing to take seriously the challenges presented by a tired, outdated and underperforming tax system, such proposals might just provide part of the answer.

Alfie Stirling is Senior Economic Analyst at IPPR He tweets @alfie_stirling

Related items

Rule of the market: How to lower UK borrowing costs

The UK is paying a premium on its borrowing costs that ‘economic fundamentals’, such as the sustainability of its public finances, cannot fully explain.

Restoring security: Understanding the effects of removing the two-child limit across the UK

The government’s decision to lift the two-child limit marks one of the most significant changes to the social security system in a decade.

Building a healthier, wealthier Britain: Launching the IPPR Centre for Health and Prosperity

Following the success of our Commission on Health and Prosperity, IPPR is excited to launch the Centre for Health and Prosperity.