Covid-19 and the case for a digital commons

Article

The Covid-19 pandemic has imposed, and will continue to impose, drastic changes in how we work and live. But whilst the long-term health implications of SARS-Cov2 remain uncertain, it is already clear that it is accelerating some economic trends apparent well before the discovery of a novel virus was announced by the World Health Organisation on 9 January this year. The retreat from globalisation and the re-emergence of the state as a strategic economic actor have been widely noted. But perhaps most striking is the accelerating growth of the data economy, and, with it, the rapid expansion of the digital giants who dominate it.

As IPPR’s new report, Creating the Digital Commons, makes clear, the data economy was already of an immense size. Approximately 25 quintillion bytes of data were created every single day, ahead of the pandemic, and that volume is growing exponentially. To put it in perspective, by 2017, 90 per cent of the world’s data had been created in the two years preceding. This expansion of the sheer scale of the data economy brought with it the overwhelming domination of the very few companies managing this growth. Predominantly US-based, the platform giants had, in the ten years since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, grown to become the world’s largest companies by value. The collection, processing, and application of data had shifted companies like Google, Amazon or Alibaba into positions where virtually no other part of the economy (or society) was left untouched by their operations; Artificial Intelligence (AI), based on machine learning techniques themselves dependent on the processing of vast quantities of data, as well as the expansion of 5G and the “Internet of Things” are set to reinforce this domination.

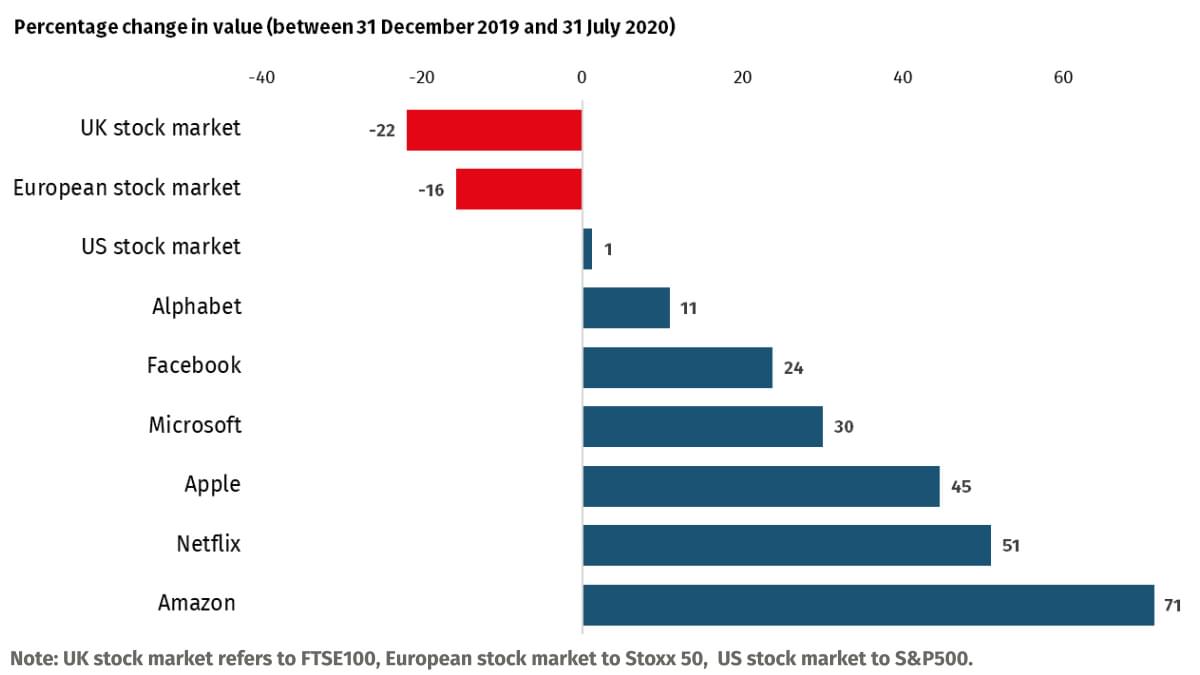

Covid-19 has disrupted entire sectors: aviation, hospitality, and entertainment are likely never to be the same. For a period in May, shares in teleconferencer Zoom were worth more than the world’s seven largest airlines added together. But whilst there are a few new entrants into the expanded digital economy, the overwhelming beneficiaries have been the existing entrants. New figures from the IPPR show that the stocks of six US digital giants have risen in value by $1.9 trillion, or 38 per cent, since the start of the pandemic, while the rest of the economy has suffered (see chart). This increase in their valuation reflects both the current dominance of Big Tech, and (not unrealistic) market expectations of continued expansion.

The value of six big tech firms has grown by between 11 and 71 per cent since the pandemic began - a total increase in their market capitalisation of 38 per cent, or $1.9 trillion. Meanwhile, the rest of the economy suffered

The pandemic and the data economy

There are two major routes through which Covid-19 has accelerated the growth of the data economy. The first, and perhaps the most obvious, is in the imposition of social distancing measures, most dramatically in the form of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders, which have seen an extraordinary transfer of activity online. At the height of the first UK lockdown in May, 49 per cent of British employees reported that they had worked exclusively from home in the previous week – up enormously from the 5 per cent who reported regularly homeworking in 2019. The possibility of homeworking varied enormously by sector, but nonetheless the impact was clear: broadband use rose dramatically across the globe during the first months of the pandemic, with BT reporting 60 per cent more data being uploaded and downloaded over its own network.

The other element of the increase in data use is less obvious, but nonetheless persistent, and this is the expansion of medical monitoring as part of the expansion of biosecurity measures in the wake of the pandemic. Some of these are well-known, and subject to major public debate, like the attempted implementation of contact-tracing software reliant on very widespread mobile phone use, and, where relatively successful - as in South Korea - a significant increase in the volume and intensity of data being gathered from individuals. Using data gathered from existing sources including mobile phone use, card payments and social media access, the Chinese authorities were able to track the movements of those who visited the market in Wuhan at the pandemic’s centre. Data on smart bracelets and watches, providing the information on the resting and waking heartrates of 115,000 people in nearby Anhui province, has been additionally used to help build a machine learning forecasting model for future Covid-19 outbreaks.

Other expansions of biosecurity technologies are less widely-debated, but also imply a significant expansion of monitoring and data collection: Amazon has introduced infra-red sensors in some of its warehouses to monitor staff temperatures and proximity, whilst temperature checks for commuters are being considered by the UK government. With the boundary between work and home becoming blurred (or even “obliterated”) under lockdown, workplace surveillance has crept further into private houses. Meanwhile, US-based Draganfly have trialled their “pandemic drones” in Connecticut, which aim to “detect Covid-19 symptoms and monitor social distancing”.

Loss of public value

Much of the public debate around this has centred on the implications for privacy, and the lack of transparency about the use being made of data – particularly health data – by firms operating under government contracts. US data specialist Palantir has attracted particular controversy for its work on NHS data, recently extended by the Department of Health. This work has involved cleaning and organising NHS datasets for use in future machine learning and other data-based healthcare technology; although Palantir itself was initially paid a peppercorn fee for the work, the future value of data prepared for further processing is enormous.

But the major social gains from data come when it can be operated at scale. Google is an effective search engine (amongst other things) because it operates vast databanks. The value of social networks like Twitter or Facebook is directly tied to their size. Machine learning is dependent on access to large, high-quality datasets. Competition policy alone, at least in the sense of simply trying to break up some of these digital giants, could both reduce the value to the public of operating at scale – and, by creating smaller digital companies with similar business models, could simply reproduce some of the socially damaging behaviour we have seen.

Instead, IPPR’s new report argues that competition policy alone is not the answer, and that ways to pool, share and use data must be developed, so it can be used for public benefit rather than private profit. We call this a “digital commons”, based on the idea that the value of data is a shared, social resource, and lay out ways in which governments, locally and nationally, can better manage this new source of value.

To achieve this, the report calls for a series of changes by national government including:

Creating a new UK Office for the Digital Commons, with strong regulatory powers over existing digital service providers and a duty to intervene in favour of open data, and to ensure public benefit from all data.

Establishing a widely understood definition of a new kind of ‘data trust’, distinct from conventional trusts, and ensuring resources are available to promote their creation and use.

Protecting valuable UK digital data, such as that derived from the NHS, from unfair international exploitation – notably in trade deals after the UK leaves the EU.

It also recommends steps to bring the value created by data under local and regional control, as is already being pioneered by innovative cities such as Amsterdam and Barcelona. Local authorities, metro mayors and devolved administrations can do the same in the UK, including by:

Using their procurement powers to begin building a local digital commonwealth by compelling companies to share data as a pre-condition of winning a service contract, and to build the use of data for local public good into their guidelines.

Pushing for locally collected data to be made open to use by others in anonymised form as a matter of course, as with TfL’s open-source data on transport use in London.

Ensuring that newly developed digital infrastructure, such as smart power grids, is held under local and democratic control.

Related items

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.

Delivering control and compassion: Reflections on the home secretary's speech on immigration reform

The last six months for the home secretary have been quite a whirlwind.