The hidden cost of Covid-19 on the NHS - and how to ‘build back better’

Article

The NHS appears to have managed Covid-19 reasonably effectively, but this ignores the hidden cost of the pandemic to non-Covid patients. Unlike some other countries, our health system in the UK was not pushed to breaking point as a result of the pandemic. In the end the surplus capacity created by new Nightingale hospitals was largely surplus to requirement. But we must be honest about how this came about. The NHS was only able to manage the spike in Covid-19 patients by withdrawing care from non-Covid patients. This has occurred both as a result of fewer people presenting for treatment (both in primary care and in A&E) and also the rationing of care - such as cancelled treatment - by the NHS, in order to free up capacity to support patients with Covid-19.

We urgently need to understand the impact of this disruption to care and put policy in place to drive recovery. Some early studies have sought to understand the impact of the pandemic on non-Covid patients. But we still do not fully understand the long-term impact of this disruption in care. Filling this knowledge gap must be a priority. We must now resolve this issue by at least returning access to, and the quality of, services to pre-pandemic levels. Crucial will also be identifying ways to do this that would be resilient to a second wave of Covid-19. The impact of restricting care for non-Covid patients during the first wave is likely to have been hugely damaging. Repeating this approach would be catastrophic.

However, the NHS can and should do more than simply recover - it must aim to ‘build back better’ after the pandemic. Despite huge public affection for the health service, the evidence is clear that the UK lags behind many of its neighbours in terms of health outcomes. Prior to the pandemic the government put in place the NHS Long-Term Plan which set ambitious targets to improve outcomes. Covid-19 risks setting us back in attempting to achieve these. But equally we could use the pandemic as an opportunity to ‘build back better’ across all areas of health and care policy. That is the focus of a major piece of IPPR research which will be published later this year. In this short blog we set out some emerging findings from this project, using cancer care as a case study.

Cancer care after Covid-19

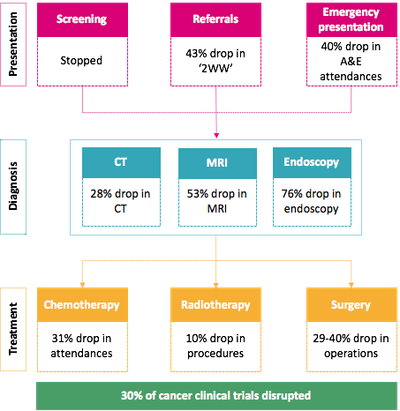

Covid-19 has led to a significant disruption in cancer services across the NHS. Activities across the whole cancer pathway have been affected by the pandemic. National screening programmes have been suspended (though unlike in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland this has not yet been formally announced in England), meaning 210,000 fewer people being screened a week. Hospitals in England have seen a 43 percent drop between April to June this year (339,242 people in total) in urgent two-week wait (2WW) referrals from GPs for diagnostic tests compared to 2019 (594,060 people). Data from May shows a 29 per cent cancellation rate of cancer surgery, equivalent to more than 36,000 surgeries. Meanwhile, treatments - and in particular chemotherapy - have also dropped (though rates have recently started to recover). Finally, clinical trials have also been disrupted.

Figure 1: Disruptions to cancer services across the pathway due to the Covid-19 pandemic

Source: CF Analysis of latest data (sources and time period can be found here)

This will likely result in delayed diagnosis and treatment for those patients affected. We know that delays in referral lead to delays in diagnosis; delays in diagnosis to delays in treatment; and delays in treatment to premature deaths. Put simply: early diagnosis and treatment can make the difference between life and death. Working with CF healthcare consulting we have analysed the potential impact of late diagnosis on cancer outcomes. We have focused on three types of cancer: lung, breast and colorectal (though the evidence suggests there have been disruptions across all types of cancers including blood cancers). Across all three we have assumed that the pandemic leads to diagnosis occurring one stage later than would otherwise have been the case for affected patients with disruption seen over a three-month period. These assumptions are our best estimate of the impact given the duration of the effect and the implications of this for the stage of diagnosis are uncertain given the unprecedented nature of Covid-19.

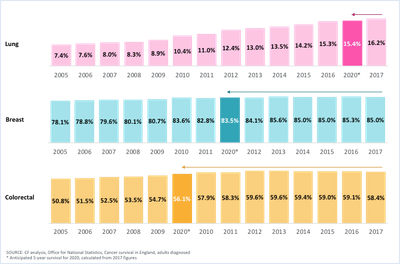

Figure 2. Five-year survival over time and anticipated for 2020, in England

Source: CF analysis

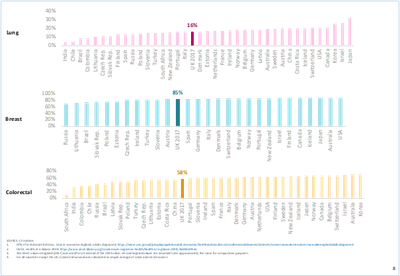

If this scenario plays out the impact on cancer outcomes will be significant for those affected. Our results show that for lung cancer, five-year survival stands to drop from 16.2 per cent to 15.4 per cent, for breast cancer from 85 per cent to 83.5 per cent, and for colorectal cancer from 58.4 per cent to 56.1 per cent. These declines would be significant. They would imply a loss in progress (e.g. outcomes equivalent to those in previous years) of one year, six years, and eight years respectively (see figure 1). There is also a high risk that this could leave us lagging behind other countries (depending on the degree of disruption to other countries’ cancer services). Based on our modelling results our cancer outcomes would be equivalent to those of countries such as Turkey, and Lithuania before the pandemic. They would also put us significantly behind target in meeting the objectives set out in the NHS Long-Term Plan.

Figure 3: Five-year survival rates across OECD countries, latest year

Source: CF analysis

The case for ‘building back better’

There is an urgent need for the government to put measures in place to restore the NHS’s performance. This must mean quickly addressing the backlog of cancer care, which is thought to be impacting up to 2.4 million people through urgent referrals alone. But there is also a need to recover diagnostics and services for new patients. The government deserves credit for launching a publicity campaign to encourage people to seek help when they have symptoms, and for putting in place plans to make cancer care Covid-19 safe. But it can and must go further. We recommend that the government:

- Makes diagnosis and treatment of cancer “Covid-safe’ - and ensures the public perceive it to be so - by moving diagnostics out of hospital where possible (and especially in hospitals that treat Covid-19 patients) and guaranteeing regular Covid-19 tests for all cancer staff and patients. Given patient and staff numbers, our calculations suggest that this commitment alone would require between 124,000 and 172,000 Covid-19. tests per week.

- Increase diagnostic and treatment capacity in the NHS as quickly as possible. This is needed both to quickly deal with the backlog and to compensate for reduced productivity as a result of the safety precautions introduced to manage Covid-19 (e.g. cleaning procedures). In the short run this may require continued use of private sector capacity.

But the NHS must use the disruption of Covid-19 to go further and look to ‘build back better’. Covid-19 has exposed the existing weaknesses in our health system. In terms of cancer, these issues span public health and clinical care (particularly for diagnostics). We do not have to revert to the pre-Covid status quo. We can use the disruption of the pandemic to design a better, more resilient system. We recommend that the government:

- Builds on the recent obesity drive in the form of a comprehensive new public health strategy to prevent illness, as committed to in the Conservative 2019 manifesto, spanning the main causes of cancer (such as alcohol consumption and smoking) across both adults and children. This should include restoring the public health grant worth £1bn per year.

- Increases diagnostic and treatment capacity by committing to match OECD levels of CT and MRI machines. There is also a need to scale up capacity on endoscopy and on radiotherapy equipment, and to embrace new technologies and treatments where possible. IPPR has previously called for the government to match OECD levels of capital spending to achieve this. This will also require a corresponding increase and redesign of workforce capacity.

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to Ben Richardson, Scott Bentley and Nour Mohanna of CF Healthcare Consulting for their analysis for this piece and to David Wastell, Robin Harvey, Chris Thomas and Clare McNeil from IPPR for their insight. The author would also like to thank all of the supporters of the Better Health and Care Programme: AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Lilly UK, AbbVie, Janssen and Siemens Healthineers. Abbvie and Janssen have also provided financial support and comment for this particular piece of research. The authors have retained full editorial control.

Related items

Levelling the playing field: The BBC, Big Tech, and the case for a bold charter

The upcoming charter renewal is the moment to give the BBC the resources, freedom and mission it needs to engage with technology firms on its own terms.

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.