Ethnic inequalities in Covid-19 are playing out again – how can we stop them?

Article

IPPR and Runnymede Trust

Once again Covid-19 is running along racial lines. Despite the inequalities exposed earlier this year, there has been little effort to stop Covid-19 hitting minority ethnic communities hardest as we enter the second wave. Without urgent action, the effects of pandemic are set to be felt unequally again. Already the latest national infection rates are over four times higher in Pakistani communities than white communities. Addressing these inequalities – and reducing the impact of Covid-19 on black and minority ethnic communities – is an issue of racial justice. Our goal must be a fairer and more racially just society. But it is also a vital part of our efforts to control Covid-19. Structural inequalities fuel pandemics: addressing them is crucial to avoid more severe lockdowns.

The extra risk of death in minority ethnic groups is one of the starkest health inequalities in recent times. Between March and May 2020, men and women from all ethnic minority groups (except females of Chinese ethnic background) had a greater risk of death from Covid-19 compared to those of white ethnic background. The death rate was 3.3 times higher for black males and 2.4 times higher for black females compared to white males and females. To put this disparity into context, our analysis with CF healthcare consultancy estimates that over 2,500 deaths could have been avoided during the first wave in England and Wales if the black and south Asian populations did not experience an extra risk of death from Covid-19 compared to the white population (after adjusting for differences in age and sex). Put differently, we estimate over 58,000 and 35,000 additional deaths from Covid-19 would have occurred if the white population had experienced the same risk of death from Covid-19 as the black and south Asian populations respectively.

Comorbid diseases, like diabetes, don’t explain the inequalities. New analysis with CF finds that underlying diseases (such as heart disease, lung disease and diabetes) are not driving the inequalities. The prevalence of these diseases vary between ethnic groups, but when considered together, they do not explain the difference in risk of death from Covid-19 between ethnic groups (Figure 1). We estimate comorbidities lead to the black population being only five per cent more likely to die from Covid-19 than the white population. Higher deprivation levels explain the disparities to a greater extent, but the majority of the additional risk of death from Covid-19 experienced by minority ethnic communities is unexplained. This reflects the difficulty of linking health and social data, and the paucity of data on ethnicity. Some commentators have looked to fill this void with claims about genetic differences. But the evidence is clear – there is no genetic basis for race or ethnicity. Genetics cannot explain why every minority ethnic population, given huge genetic diversity within and between these groups, has a higher risk of death from Covid-19 than the white ethnic population. Instead, this inequality is likely to be driven by structural and institutional racism that results in differences in social conditions (such as occupation and housing) and differential access to healthcare.

Figure 1: Relative risk of death from Covid-19 attributable to deprivation, comorbidities and unexplained (these risks multiply rather than add)

Source: CF analysis

We cannot resolve these inequalities overnight, but we can reduce them ahead of a second wave of Covid-19. The structural and institutional racism driving these inequalities cannot easily be undone. This requires new research to better understand the nature of these inequalities and a long-term shift in social attitudes as well as policy. But Covid-19 cannot be allowed to run unchecked through minority ethnic communities in the meantime. We do not have the luxury of waiting for initiatives such as the government’s new Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities to act. We must take bold action to protect and support minority ethnic communities now.

We are calling on the government to set out a comprehensive strategy to mitigate ethnic inequalities this winter. Our research suggests this strategy should tackle two key inequalities:

- Firstly, almost all minority ethnic groups are more likely to get Covid-19. The government must therefore put in place measures to better protect these communities and support people to isolate.

- Secondly, the consequences and harms associated with Covid-19 for most minority ethnic groups, once they have caught it, are more severe (as we set out below). This means the government must ensure that minority ethnic groups have better access to treatment than they currently do.

PROTECTING MINORITY ETHNIC COMMUNITIES

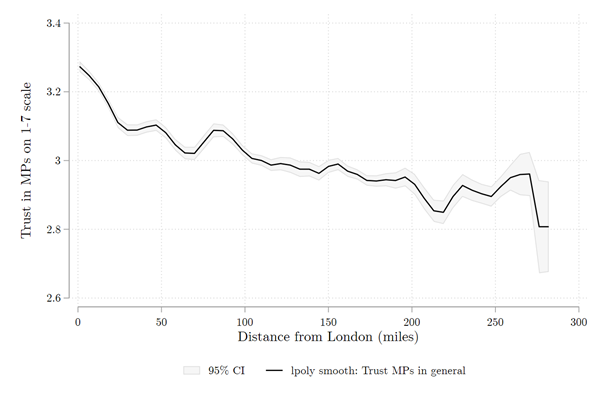

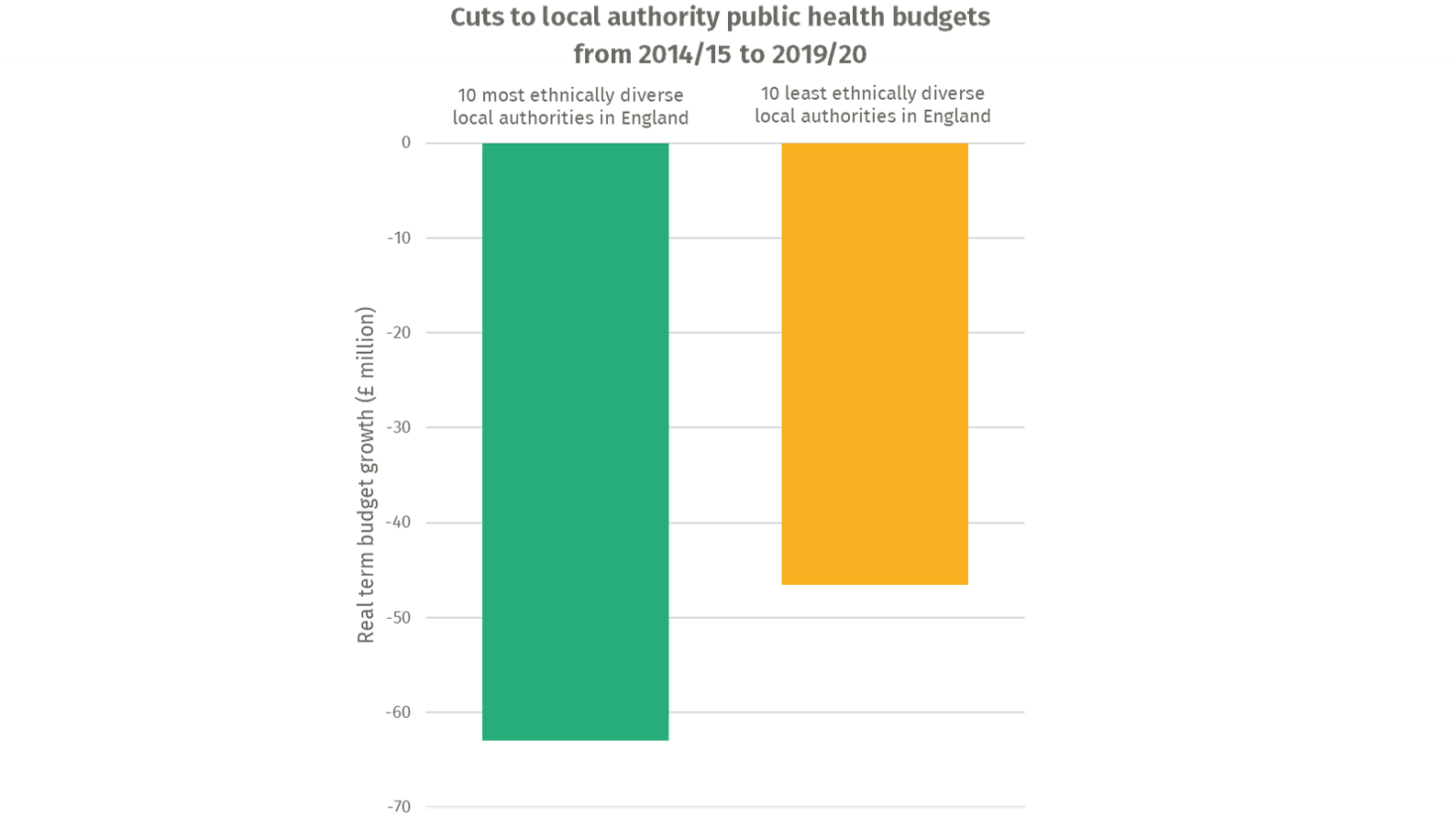

There has been no concerted action to better protect minority ethnic communities from Covid-19. A survey earlier this year found non-whites groups were on average 18 per cent less likely to have heard of the government’s stay at home advice. Despite such evidence, the task of communicating and translating public health messaging has largely been left to voluntary groups and under-resourced local authorities. Our analysis finds that minority ethnic communities have suffered disproportionately from public health budget cuts in recent years. Since 2014/15, the ten most ethnically diverse local authorities have suffered over £15 million more in public health budget cuts compared to the ten least ethnically diverse local authorities (Figure 2). Ethnic disparities in Covid-19 are a manifestation of a longer negligence. As roll out of the NHS Covid-19 App risks exacerbating ethnic inequalities, the work of local teams to protect people in more vulnerable circumstances must be better supported.

We recommend that the government:

- Delivers an emergency health protection funding package to all local authorities this winter. Working with religious and community leaders is a key aspect of the Local Outbreak Plans devised by directors of public health. Councils like Newham have successfully developed networks of residents to share information within their neighbourhoods and communities. These community-based approaches are critical to reach marginalised populations, who are often less likely to receive and act on public health messaging, as we learnt from the HIV and tuberculosis epidemics. Despite this, and despite local teams outperforming the national Test and Trace Service on successfully tracing contacts, the funding has been asymmetrical. Local authorities have received an additional £300m for contact tracing this year, while the centralised Test and Trace Service received £10bn. The government is now reluctantly accepting the need to further fund local authorities – but selectively putting money into high alert places after the infection rates are already very high is not effective. An emergency funding package for all local authorities is needed to help them implement Local Outbreak Plans, scale community Covid-19 champion schemes, and deal with the increasing cases numbers this winter.

- Includes ethnicity as a risk factor in any triaged testing system. Ideally, the government would be able to meet the demand for Covid-19 tests as we enter the winter months. As it stands, this does not appear to be the case. If testing cannot be scale up quickly, a triage system to allocate scarce resource should be devised. This would help ensure that groups of people who are more likely to be exposed to Covid-19, more likely to expose others to Covid-19 or more at risk of suffering worse consequences from Covid-19 are able to access testing first. The government has said they will prioritise tests based on occupation and comorbidities, with key workers such as NHS staff and care workers given priority. We argue that ethnicity should also be included as a parameter in this system, particularly given the large unexplained excess risk of death for many ethnic groups.

Figure 2: public health budgets have shrunk faster in the most diverse local authorities in England

Source: author’s analysis of MHCLG data

Many minority ethnic individuals find it harder to self-isolate because of the conditions in which they live and work. Nearly one third of Bangladeshi households and 15 per cent of Black African households are classified as overcrowded, compared to only 2 per cent of white households. Bangladeshi and Black African households also have only 10p for every £1 in savings held per White British household, and are more likely to expect difficulty paying their bills in coming months, meaning taking time off work to self-isolate is often unaffordable. Self-isolation is already difficult – less than 20% of people with Covid-19 symptoms isolate appropriately – but poor housing and financial precarity makes it almost impossible without additional support.

We recommend the government:

- Offers temporary accommodation to people who need to isolate but cannot do so due to their living conditions. Examples from across the world, for example in South Korea and Singapore, reveal how community isolation facilities reduce spread through families, communities and the country. The government set the precedent earlier this year by providing temporary accommodation, in the form of empty hotels, for NHS workers and homeless people. This should be scaled up this winter to provide accommodation to all who need to isolate but live in difficult conditions. This policy would simultaneously support the hard-hit hospitality sector.

- Ensures that isolation pay support is available to all, including those with no recourse to public funds visa stipulations and those without immigration status. The government’s new isolation pay support scheme for low income workers is belated but welcome. This scheme pays £500 to low-income workers who cannot work from home and need to isolate. However, it is not available to more than 1.3 million individuals with no recourse to public funds or to those without immigration status. These migrant populations (of whom the vast majority are ethnic minority people) are overrepresented in low-wage, public facing jobs. Restricting this financial support is a risk not just to those unable to access it, but to public health. Local authorities, who operate the isolation pay scheme, should be permitted to make the payment available to all in need of it. This would follow precedent set earlier in the year, when local authorities were permitted to find housing for homeless populations regardless of their migration status, and the furlough scheme was made available to those with NRPF. IPPR and Runnymede Trust have previously called for NRPF to be suspended and scrapped respectively, and stand by this, while recognising this alone would no longer be enough to provide timely financial support to isolate.

INCREASING ACCESS TO TREATMENT

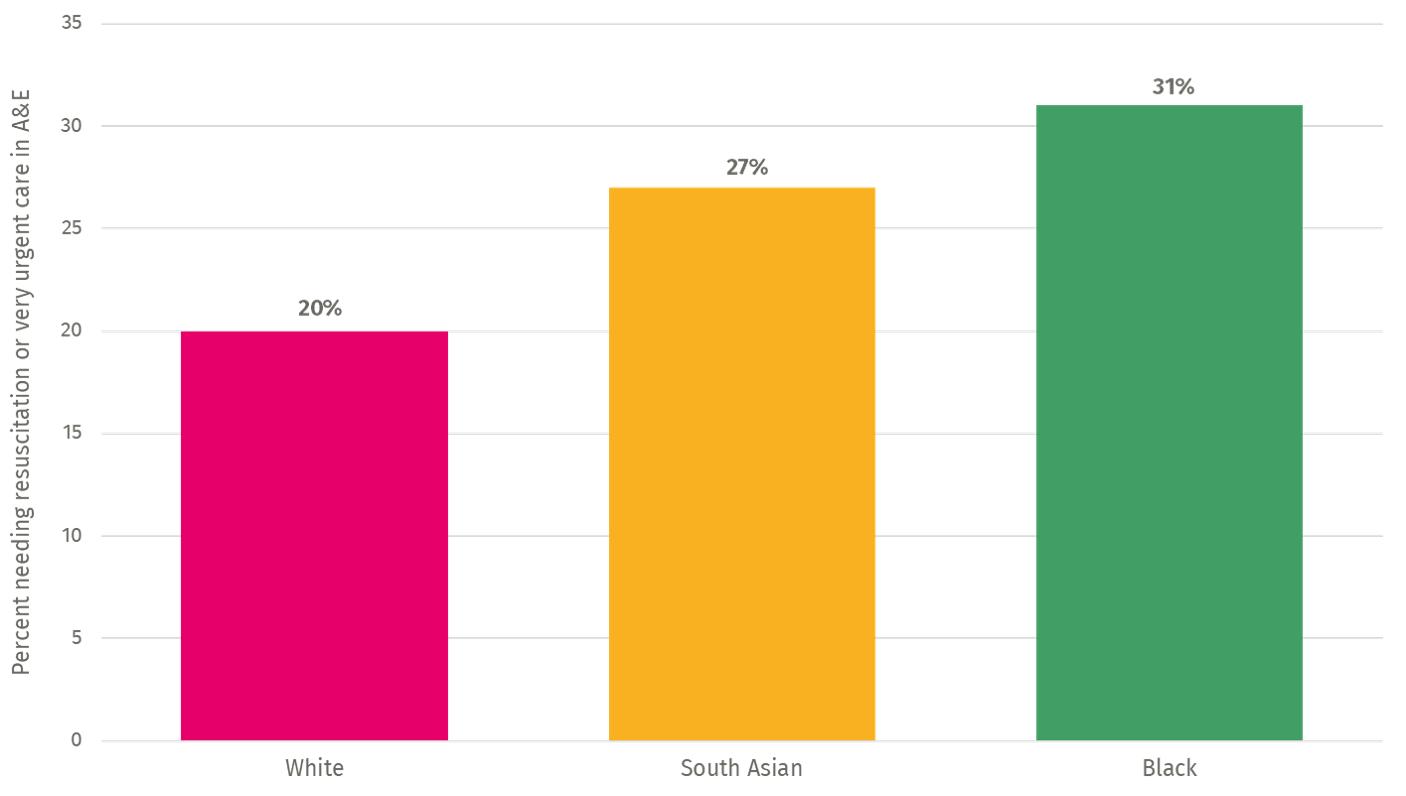

Barriers to accessing the NHS for minority ethnic groups must be removed. New research conducted with CF finds that non-white patients with Covid-19 are presenting to accident and emergency (A&E) more acutely unwell, with south Asian patients 35 per cent more likely and black patients 55 per cent more likely to need resuscitation or very urgent care than white patients (Figure 3). We also find that black patients are over twice as likely to be admitted to an intensive care or high dependency unit directly from A&E (Figure 4). This could be because these patients are not seeking timely healthcare, with late presentation leading to more severe outcomes. A recent Public Health England report found that adverse effects of the hostile environment, experiences of discrimination and distrust in NHS services have led to a reluctance in minority ethnic communities to seek care on a timely basis.

We recommend that the government:

- Immediately stops charging patients to use the NHS during this crisis. The NHS charging regulations, part of the hostile environment, demand upfront payment at 150 per cent of the cost of treatment and threaten data sharing with the Home Office. By embedding racism and exclusion into public services, they deter not just undocumented migrants but a much broader minority ethnic population from seeking timely healthcare. The government’s own equity analysis of the regulations found them to disproportionately target non-white people on the assumption they are not resident in the UK. IPPR call for these regulations to be immediately suspended and are currently investigating their impacts on patient care and fiscal benefits. Runnymede Trust call for these regulations to be scrapped.

- Sends clear, targeted messaging to encourage vulnerable populations to seek timely healthcare. The mixed messaging on accessing healthcare throughout the pandemic has been confusing for all, but compounds pre-existing barriers to seeking healthcare for minority ethnic groups. Avoiding NHS services has been fatal during this crisis. There should be a tailored public campaign to encourage timely healthcare seeking this winter, given the huge differences in severity of illness on presentation to A&E. In the longer term, health services should to be designed with people, not for them, to improve experience, build trust and increase access for minority ethnic communities.

Figure 3: Patients requiring resuscitation or very urgent care on admission to A&E by ethnicity

Figure 4: Patients admitted to an intensive care or high dependency unit directly from A&E by ethnicity

Source: CF analysis of ECDS dataset

BEYOND COVID-19

Racial inequalities are a stain on our claim to be a civilised society - it is time to address systemic racism. The measures outlined in this article will help us to control the pandemic and mitigate immediate ethnic inequalities. Failure to deliver on this agenda is not an option: this is a crisis that must be addressed. But such measures are applying a plaster to a more profound wound that could be prevented. Covid-19 has brutally exposed the racial inequalities that sit at the heart of our society. Too little attention has been paid to the socially stratified structures and stigmatisation that makes race a determinant of health. Far from being scared to add to the work of government at this difficult time, this is precisely the moment to put justice at the heart of policy and embed health in all policies. IPPR and Runnymede Trust have previously called for a national health inequalities strategy to be introduced. It is vital that racial inequalities sit at the heart of this agenda so that we can build back a better, fairer society.

Authors

Parth Patel is a research fellow at IPPR

Alba Kapoor is a policy officer at the Runnymede Trust

Nick Treloar is a research analyst at the Runnymede Trust

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Ben Richardson, Will Browne and Farhan Chatha of CF Healthcare Consulting for their analysis for this piece, and to Dan Lewer from UCL and Harry Quilter-Pinner, David Wastell, Robin Harvey and Carys Roberts from IPPR for their insights. IPPR would also like to thank all of the supporters of the Better Health and Care Programme: AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, GSK, Lilly UK, AbbVie, Janssen and Siemens Healthineers.

APPENDIX 1

During the Covid-19: Disparate Impact debate in the House of Commons on the 22nd of October a key statistic from this research was questioned by the Minister for Equalities. To clarify this, we have added a short explanatory note on the methodology we have used to produce this statistic.

Data sources and definitions

We obtained ethnicity-specific data for all recorded deaths related to Covid-19 between 2 March 2020 and 15 May 2020 in England and Wales from the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS). Data included the decedent’s ethnicity, sex and age group (9-65 years or over 65 years). Population estimates by ethnicity, age and sex were obtained from the 2011 ONS Census data, which is the latest available data.

The white ethnic group was defined as White British, Irish and other White. The black ethnic group was defined as Black African, Black Caribbean and other Black. The south Asian ethnic group was defined as Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi. Covid-19 related death was one that occurred within 28 days of a positive Covid-19 swab test.

Statistical analysis

We stratified the mortality and population data according to age group (9-65 years, >65 years), sex and ethnic group (white, black and south Asian), yielding 12 strata. Within each age group and sex, the mortality rate for a particular ethnic group was used as a reference group and applied to the other ethnic groups to produce a number of expected deaths. We then calculated the difference between the observed and expected deaths.

Using the white ethnic group as the reference population, we estimate 2,507 deaths that occurred between 2 March 2020 and 15 May 2020 in England and Wales would have been avoided if the black and south Asian populations did not experience a greater risk of death from Covid-19 compared to the white population.

Using the black ethnic group as the reference population, we estimate 58,497 more deaths would have occurred between 2 March 2020 and 15 May 2020 in England and Wales would have occurred if the white population experienced the same risk of death from Covid-19 as the black population.

Using the south Asian ethnic group as the reference population, we estimate 35,076 more deaths would have occurred between 2 March 2020 and 15 May 2020 in England and Wales would have occurred if the white population experienced the same risk of death from Covid-19 as the south Asian population.

We were unable to obtain more granular age-specific data than the coarse age groups of 9-65 years and over 65 years. We requested ONS for this data but they were unable to provide this data. Based on black and minority ethnic populations being younger than average, our estimates of 58,000 and 35,000 additional deaths is likely to be conservative.

Quality assurance

Similar methods have been used previously by Lewer et al. 2019 published in The Lancet Public Health, co-authored by the pre-eminent health inequalities expert Sir Michael Marmot.

Quality assurance for our calculations were kindly provided by Professor Robert W Aldridge (UCL Institute for Health Informatics), Mr Dan Lewer (UCL Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care) and Mr Will Browne (Head of Data Analytics, Carnal Farrar Healthcare Consultancy).

Related items

Britain's strategy for a decade of danger: Our nation, our continent, our world

Britain's foreign policy needs a grand strategy that clearly defines the country’s strategy for security, growth and migration.

Will planning reform make housing more affordable?

It is undeniable that housing in England is in crisis.

Delivering control and compassion: Reflections on the home secretary's speech on immigration reform

The last six months for the home secretary have been quite a whirlwind.